syn·site

( a ) neologism: syn-site is a neologism for a contemporary understanding of site as entangled and mutable. It offers legs (utility) for both a part (JF) and a whole (non-zero others).

( b ) gesamtkunstwerk: syn-site is one person's act of tilting at windmills syn-sites as a gesamtkunstwerk.

( c ) smeerp¹: syn-site is calling-a-nonsite-a-smeerp.

( d ) smeerp²: non-site, in turn, was calling-synecdoche-a-smeerp.

( e ) smeerp³: calling a rabbit a smeerp is a problem.

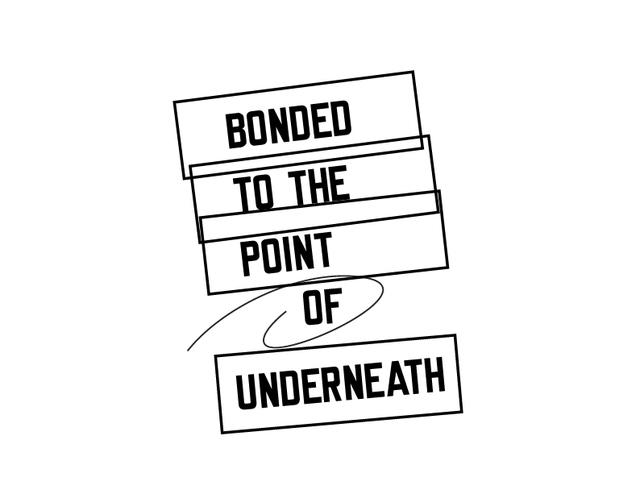

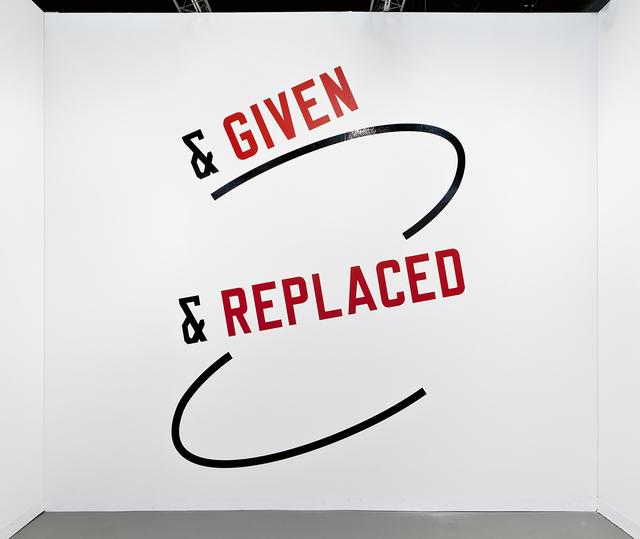

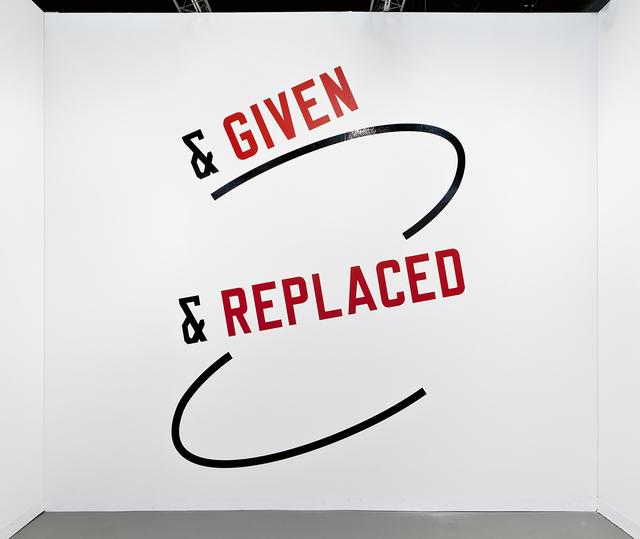

( f ) ...is a stretch...

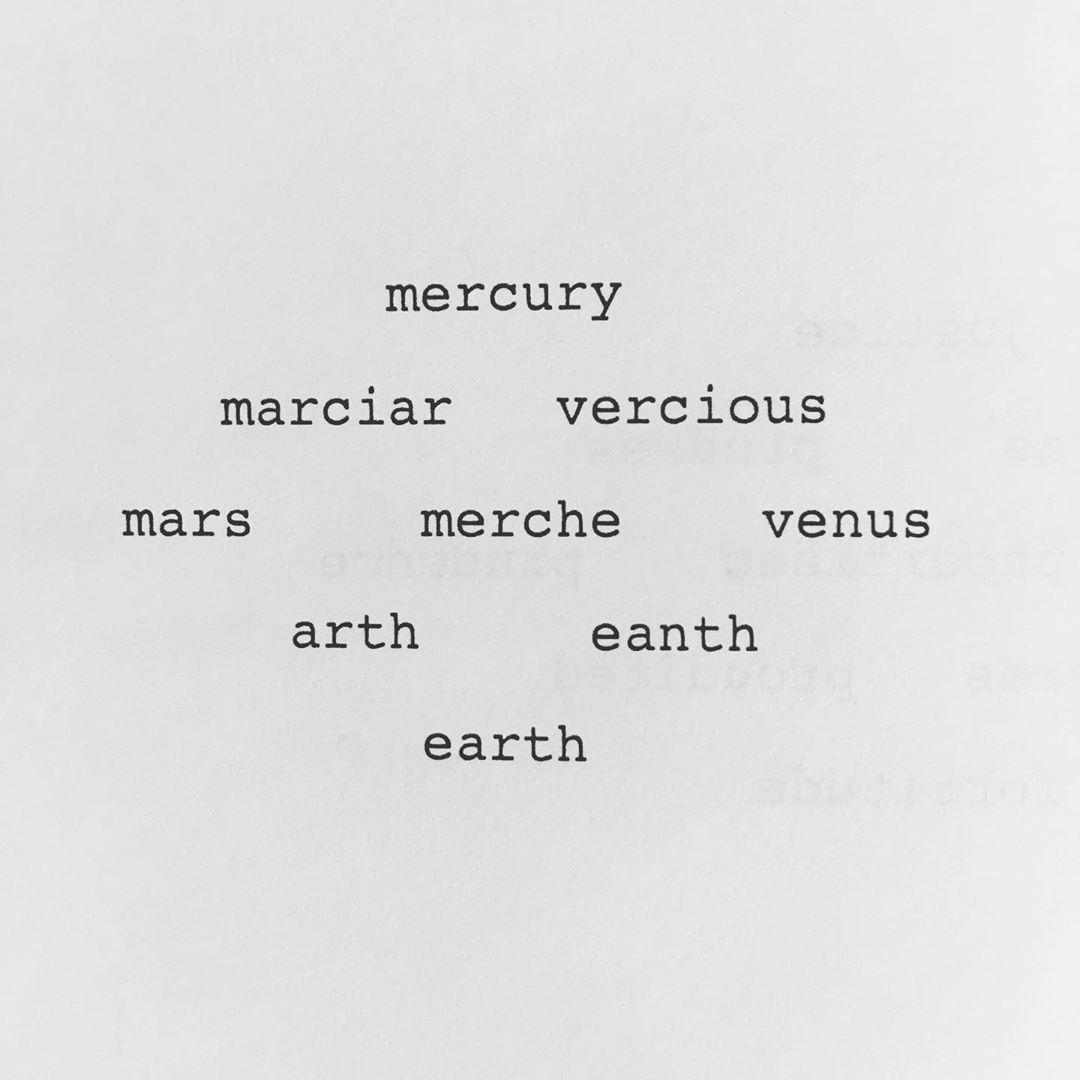

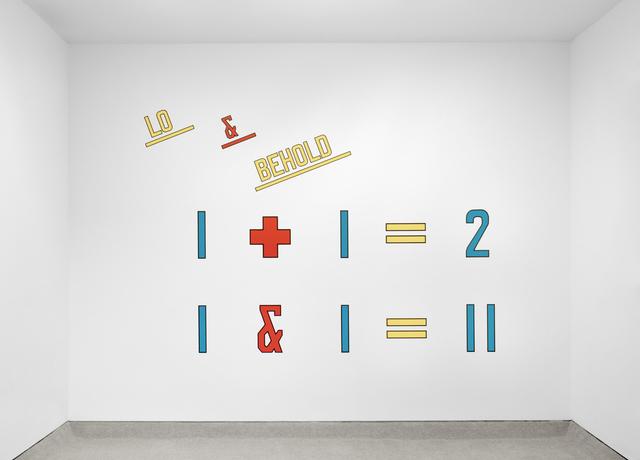

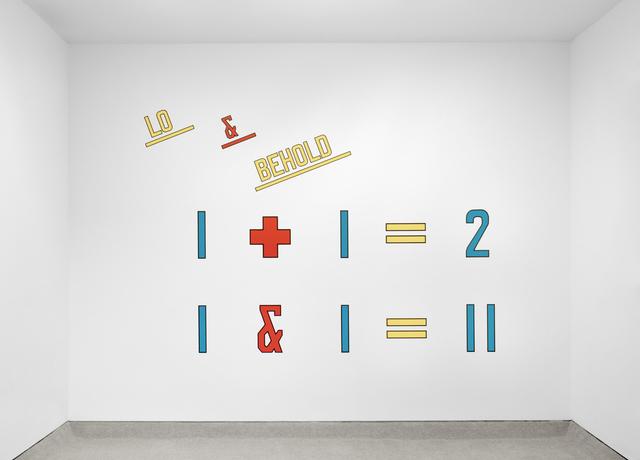

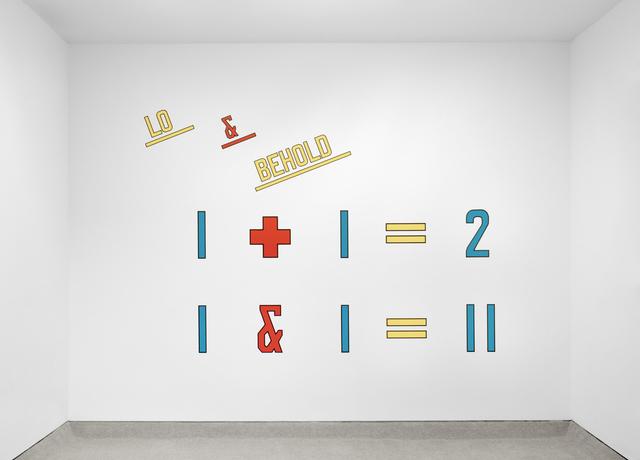

( g ) ...but art is reaching, stretching, gesturing; is making connections to create constellations.

( h ) some combo synthesis

( i ) related yet sublated-or-other: parasite, hypersite, hyperobject, nonspace, nonplace, site/non-site, synsight, syncite, knotsite, web-site, metaverse, smeerp, tangle.

( a ) neologism: syn-site is a neologism for a contemporary understanding of site as entangled and mutable. It offers legs (utility) for both a part (JF) and a whole (non-zero others).

( b ) gesamtkunstwerk: syn-site is one person's act of tilting at windmills syn-sites as a gesamtkunstwerk.

( c ) smeerp¹: syn-site is calling-a-nonsite-a-smeerp.

( d ) smeerp²: non-site, in turn, was calling-synecdoche-a-smeerp.

( e ) smeerp³: calling a rabbit a smeerp is a problem.

( f ) ...is a stretch...

( g ) ...but art is reaching, stretching, gesturing; is making connections to create constellations.

( h ) some combo synthesis

( i ) related yet sublated-or-other: parasite, hypersite, hyperobject, nonspace, nonplace, site/non-site, synsight, syncite, knotsite, web-site, metaverse, smeerp, tangle.

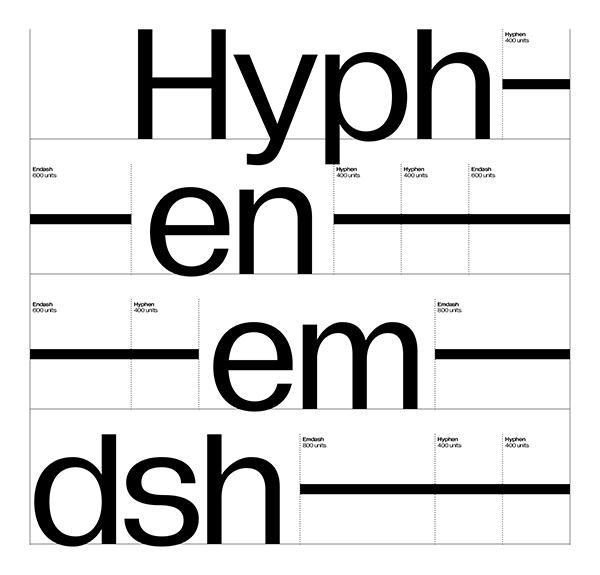

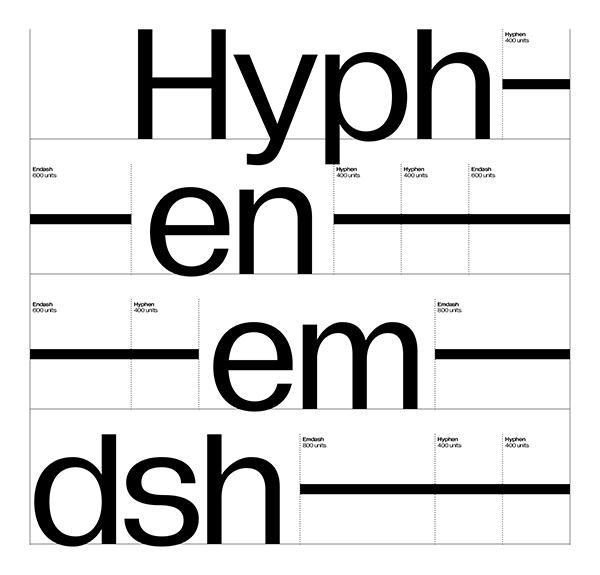

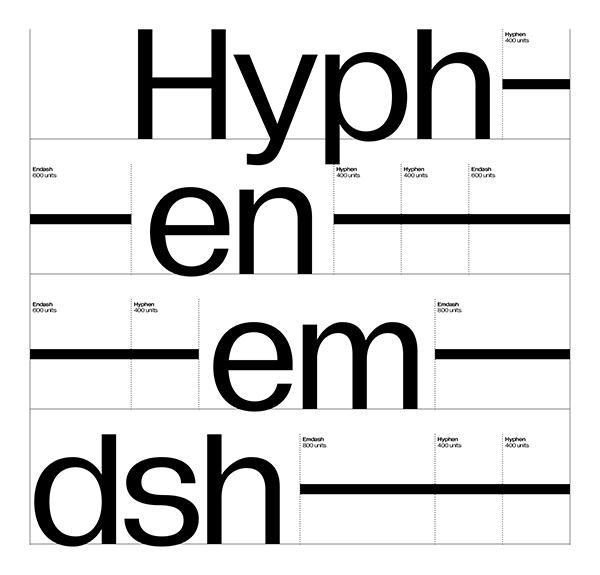

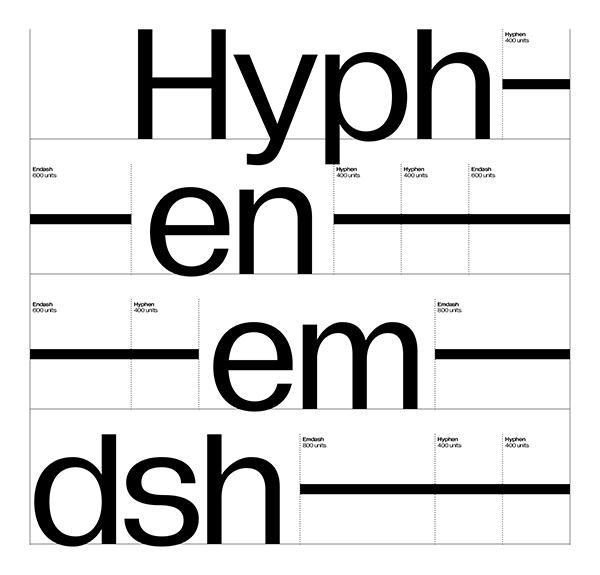

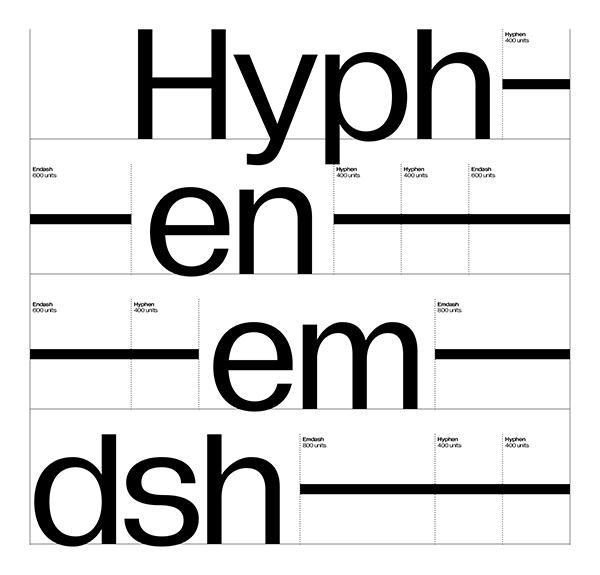

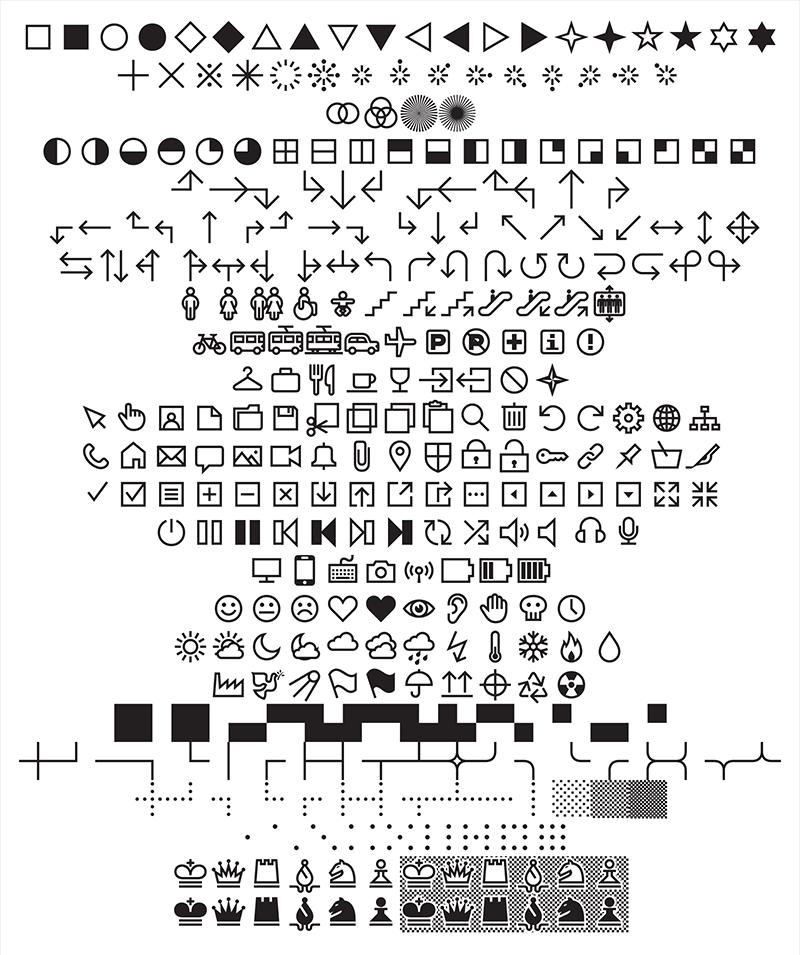

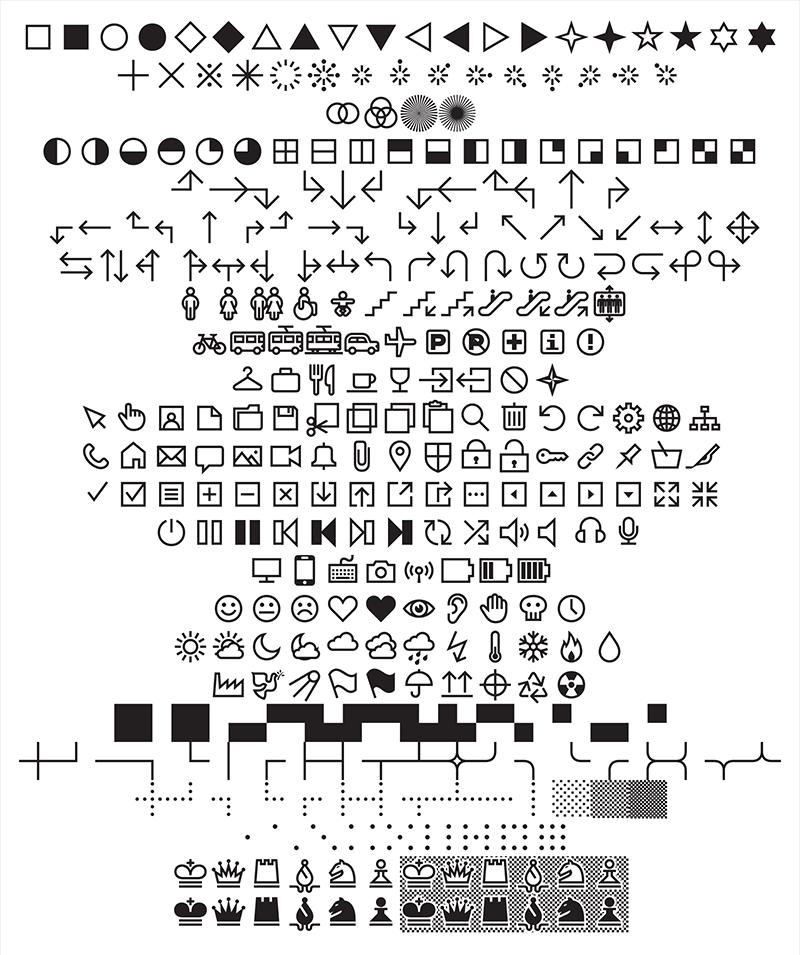

SYN (along with, at the same time | from Greek SYN, with | ~SYNTHETIC) + SITE (N: point of event, occupied space, internet address; V: to place in position | from Latin SITUS, location, idleness, forgetfulness | ~WEBSITE ¬cite ¬sight), cf. SITE/NON-SITE (from Robert Smithson, A PROVISIONAL THEORY OF NONSITES, 1968)

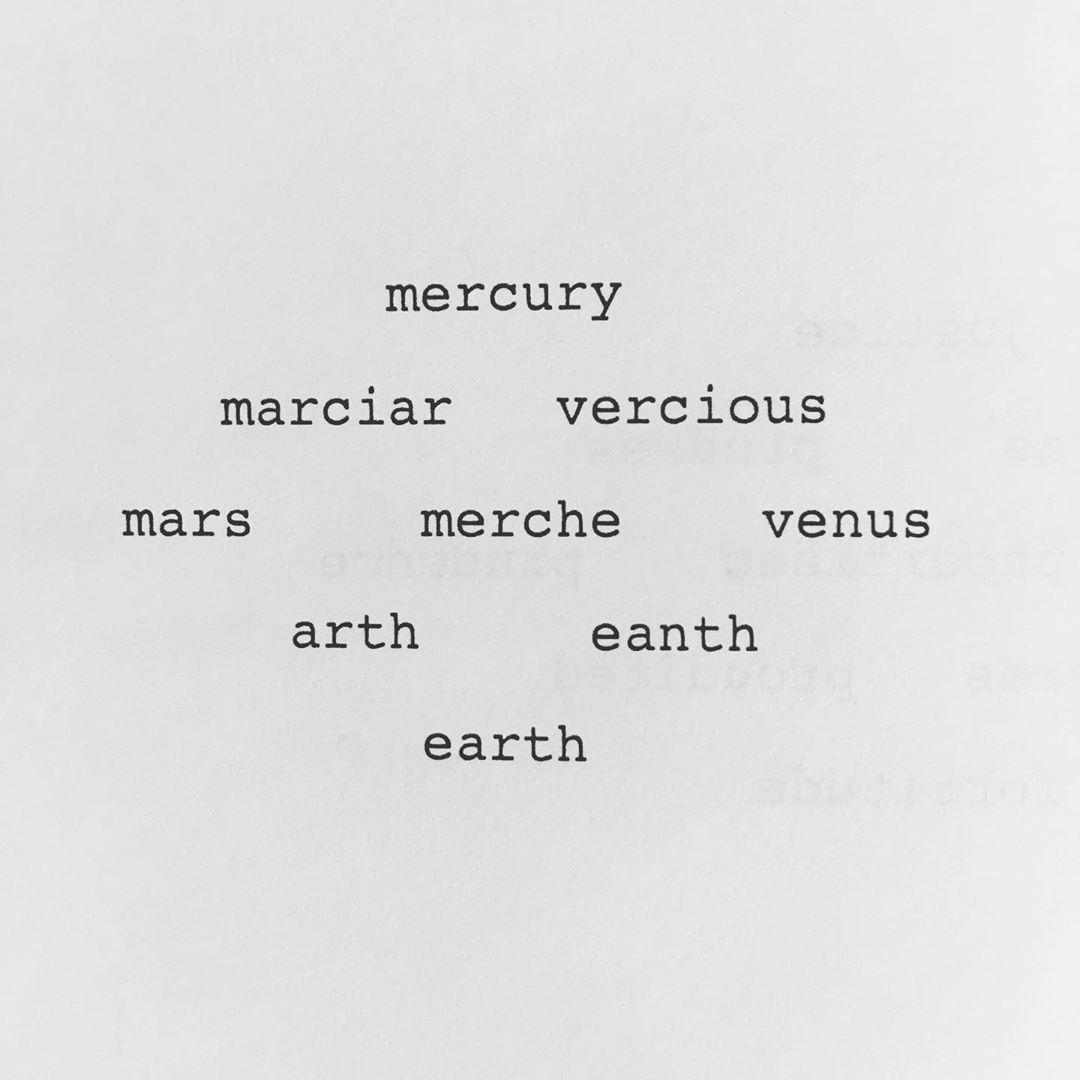

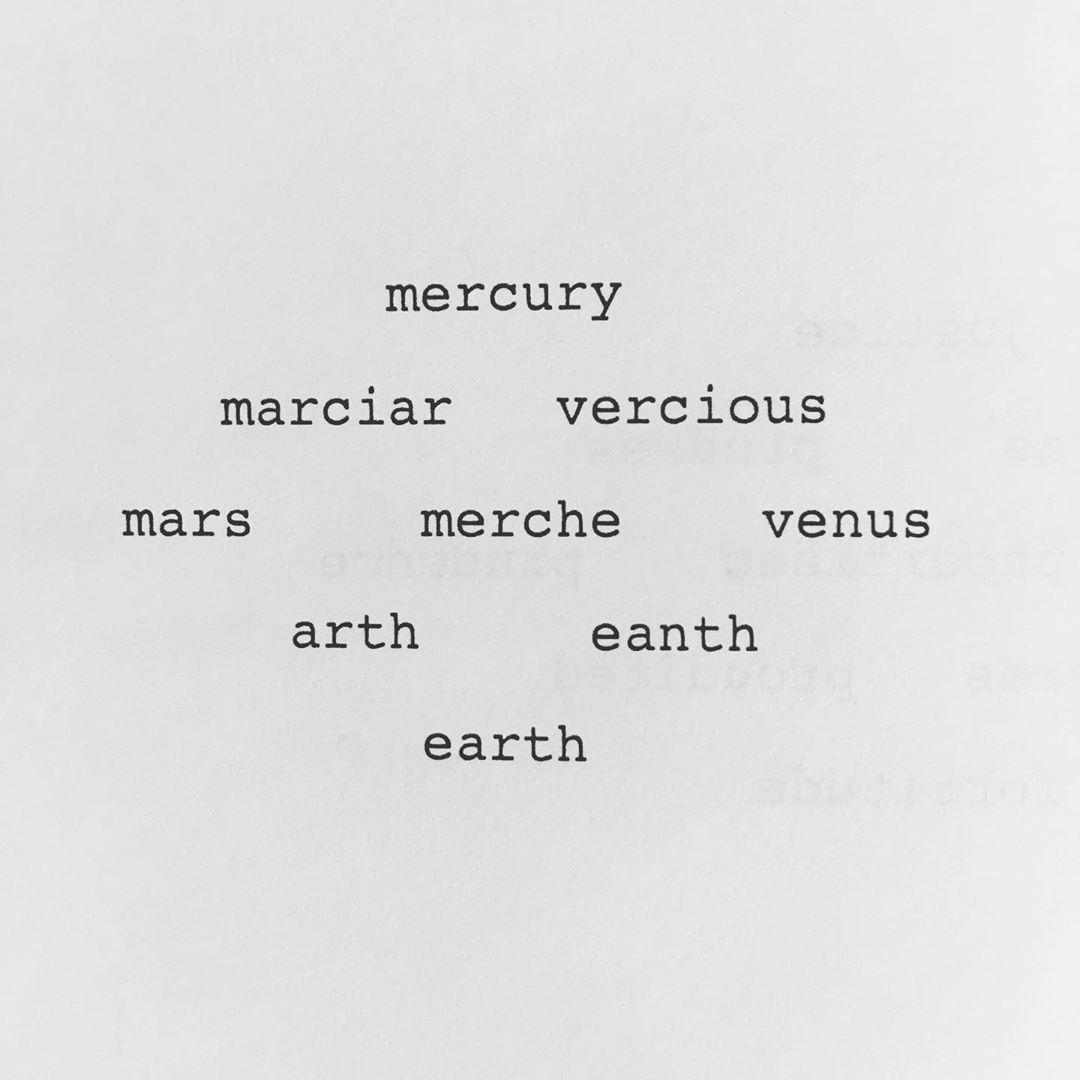

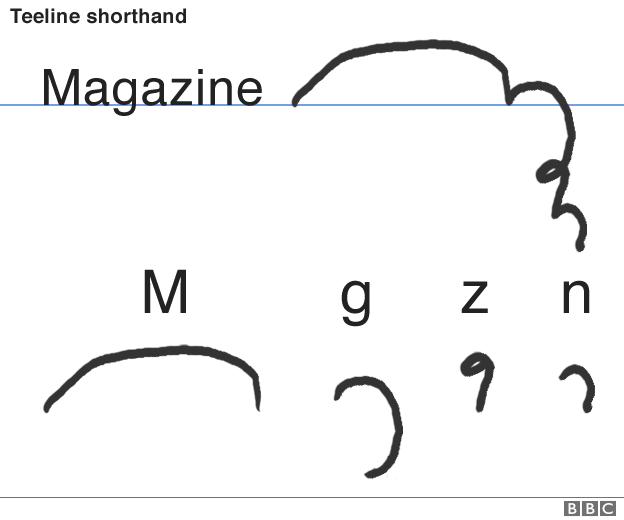

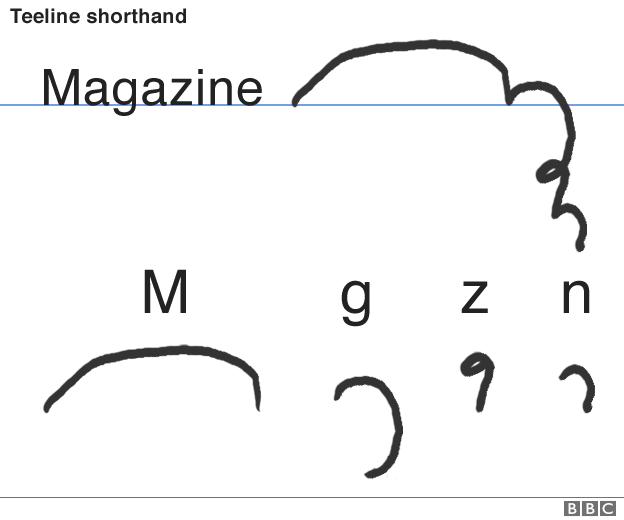

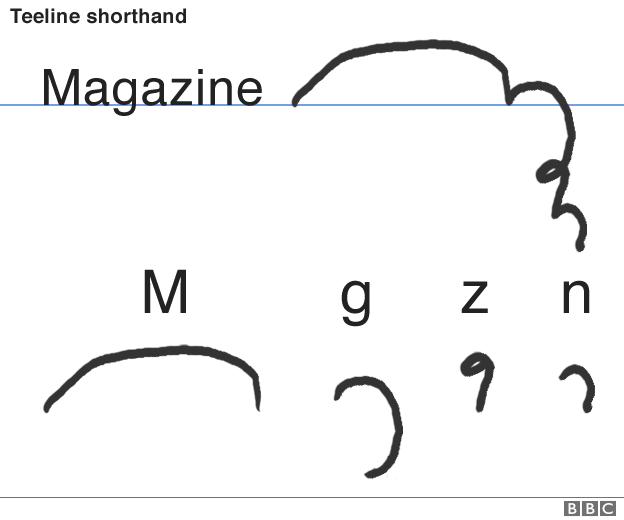

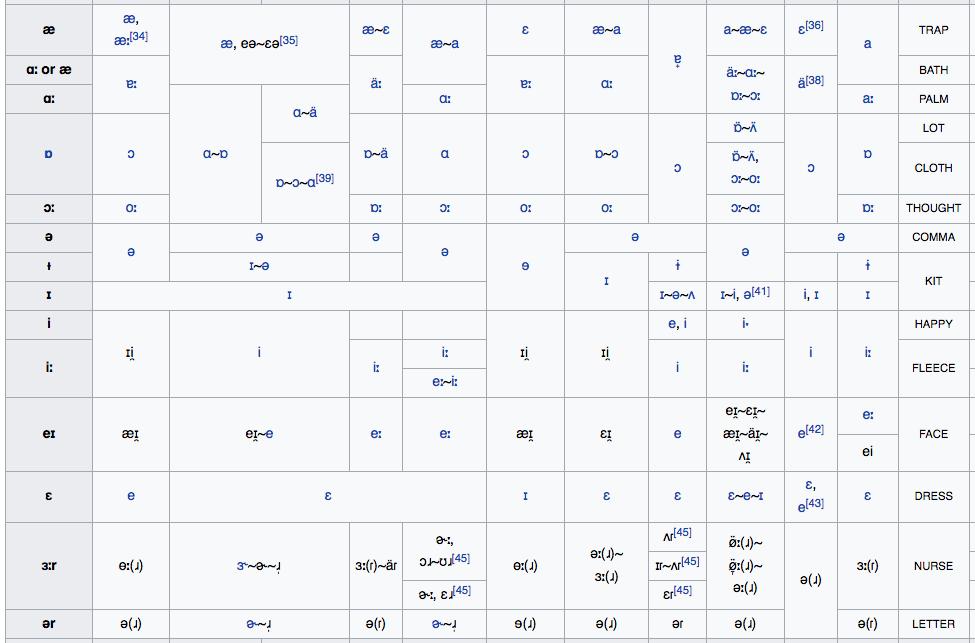

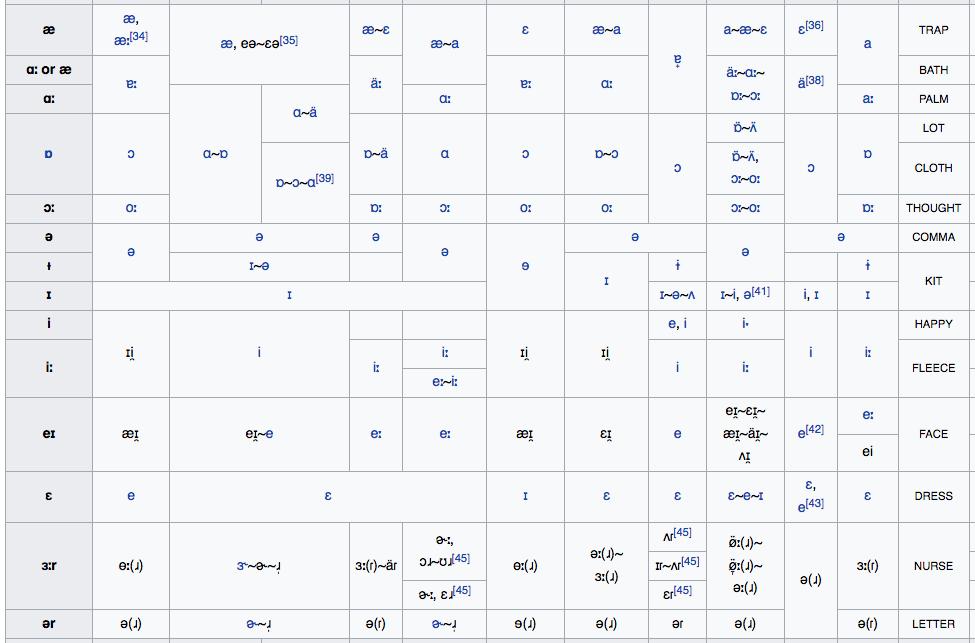

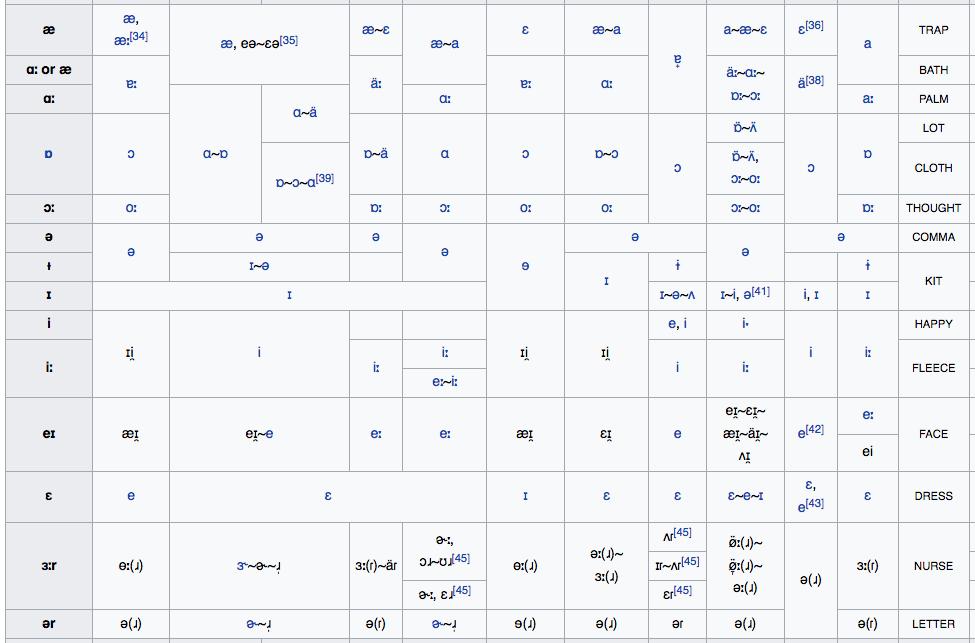

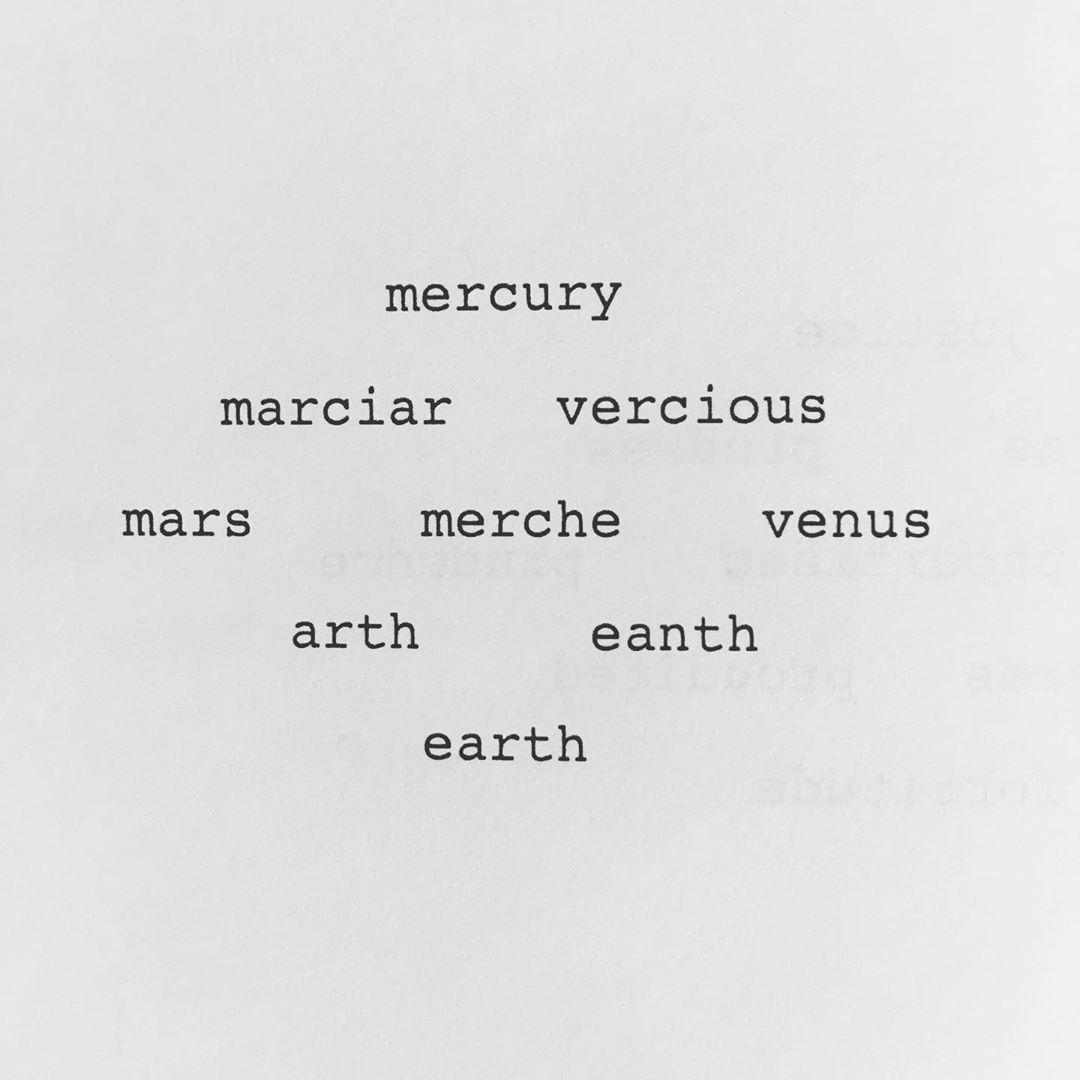

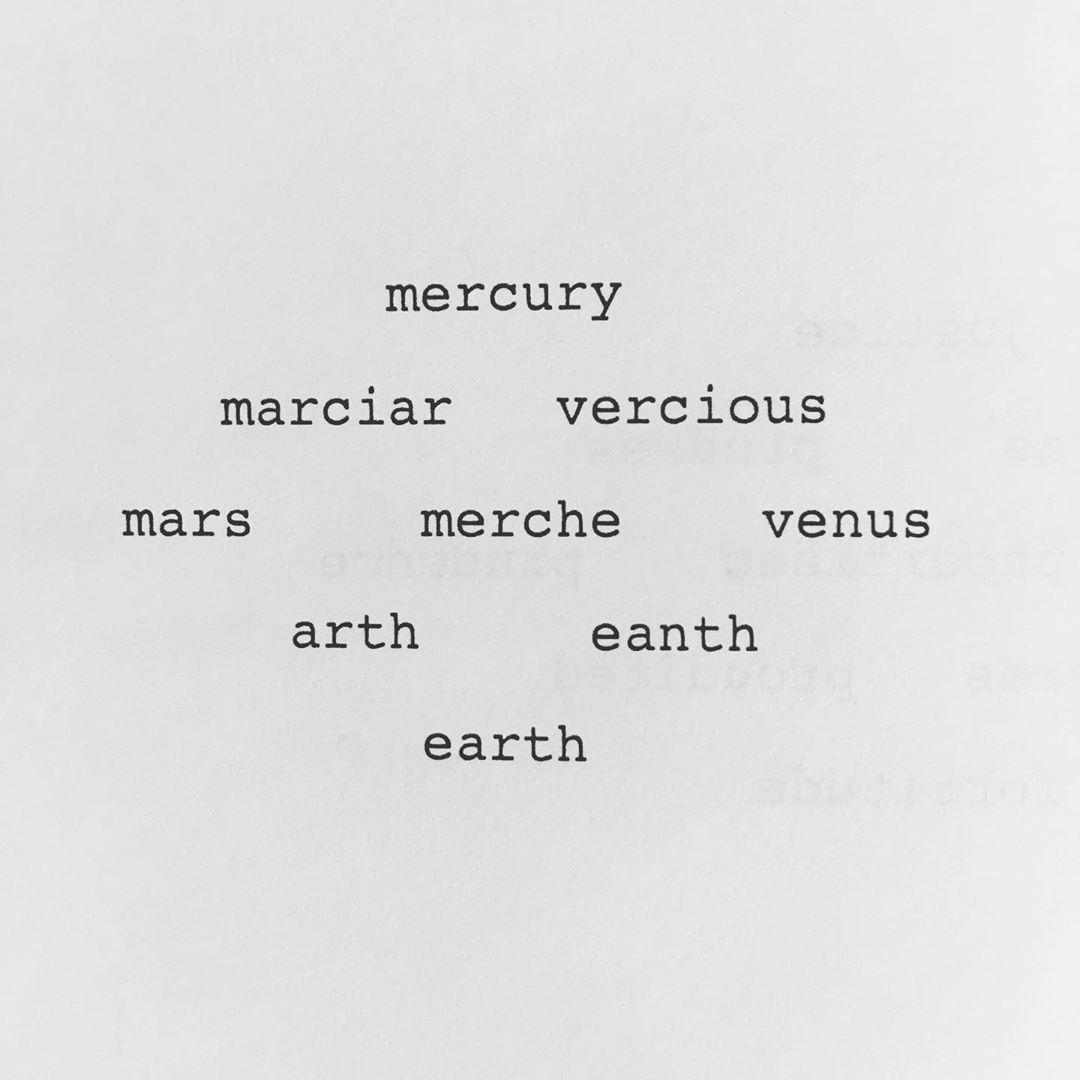

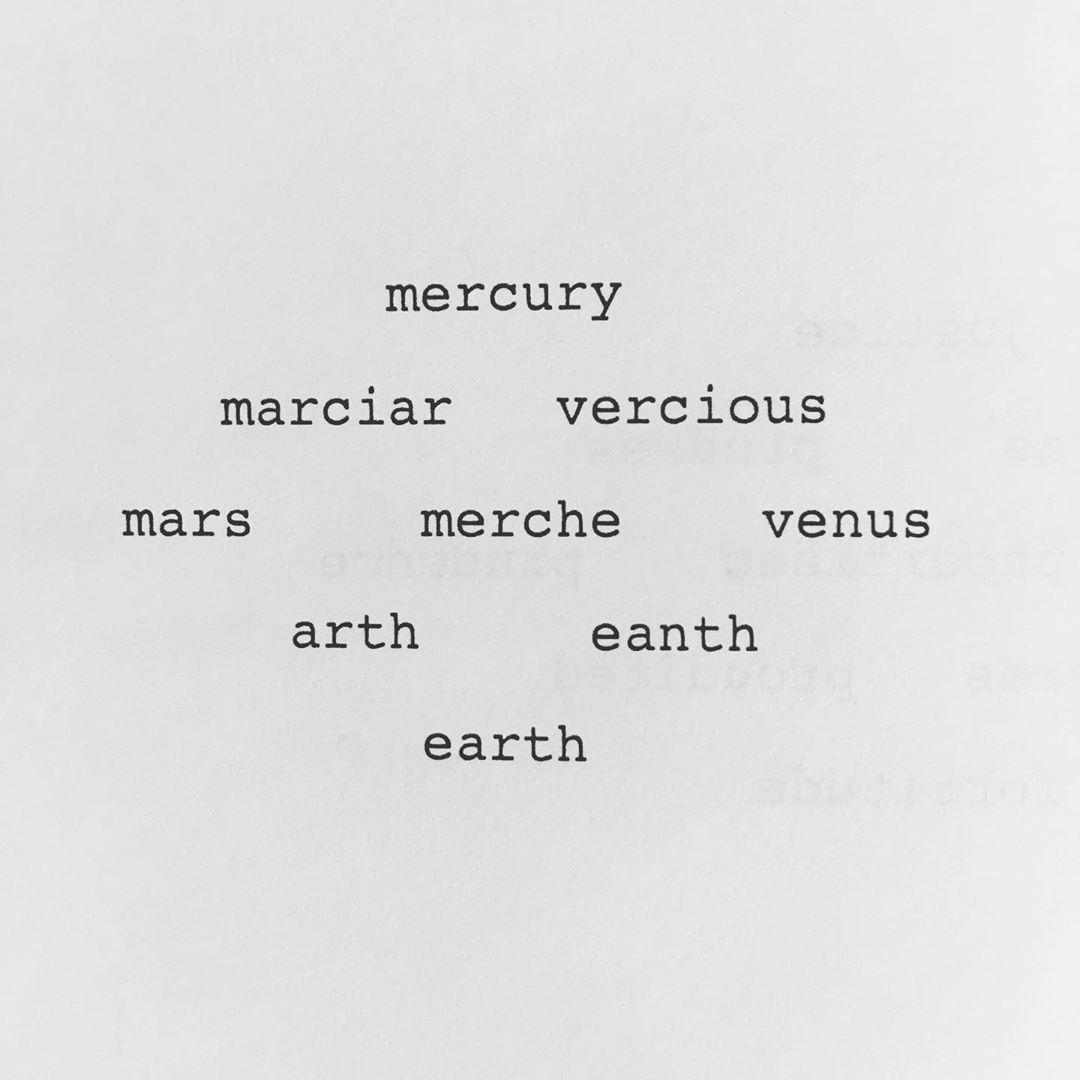

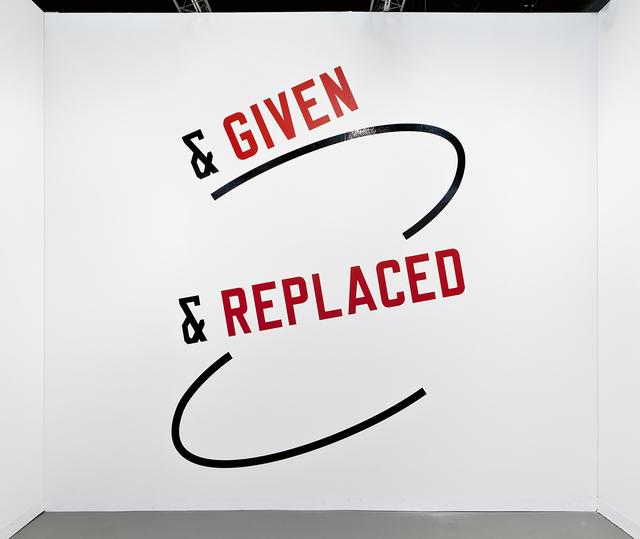

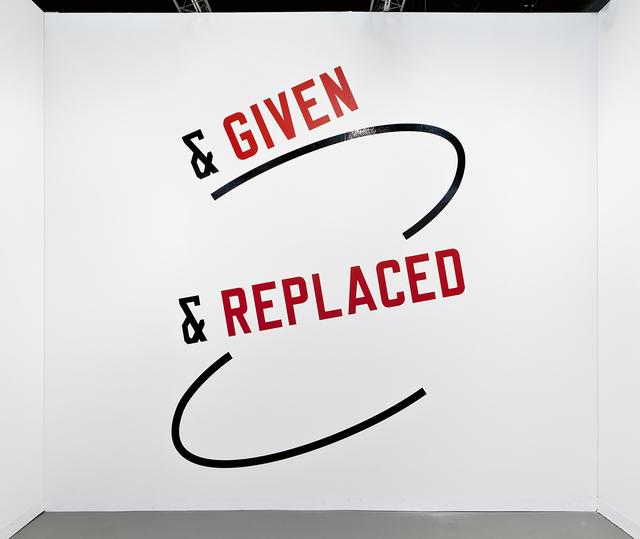

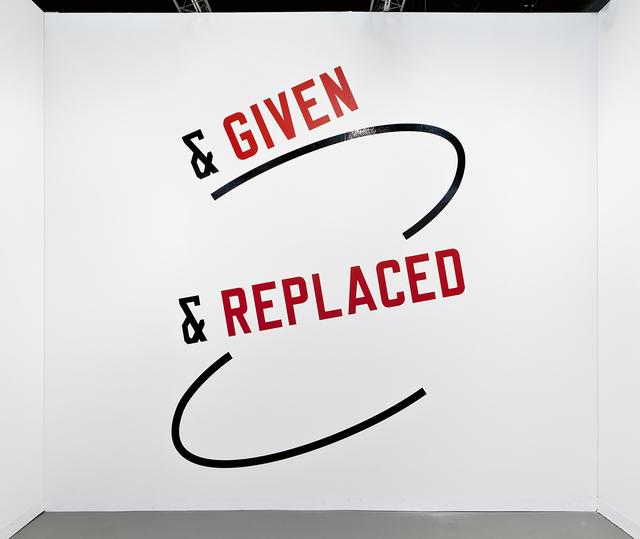

I was struck by that error, nolle and noli. Our organism of language mutates. It gets things wrong, by transcription or misunderstanding. Notice even this little clump of sentences that I’ve written: I’ve tried to respect Heaney, the ambiguity of his experience, the mourning ache of his family. (Is it an ache? Is such a word accurate? I don’t know.) But I’ve written about it all the same, and in doing so I have translated it.

I was struck by that error, nolle and noli. Our organism of language mutates. It gets things wrong, by transcription or misunderstanding. Notice even this little clump of sentences that I’ve written: I’ve tried to respect Heaney, the ambiguity of his experience, the mourning ache of his family. (Is it an ache? Is such a word accurate? I don’t know.) But I’ve written about it all the same, and in doing so I have translated it.

I was struck by that error, nolle and noli. Our organism of language mutates. It gets things wrong, by transcription or misunderstanding. Notice even this little clump of sentences that I’ve written: I’ve tried to respect Heaney, the ambiguity of his experience, the mourning ache of his family. (Is it an ache? Is such a word accurate? I don’t know.) But I’ve written about it all the same, and in doing so I have translated it.

A dictionary begins when it no longer gives the meaning of words, but their tasks. Thus formless is not only an adjective having a given meaning, but a term that serves to bring things down in the world, generally requiring that each thing have its form. What it designates has no rights in any sense and gets itself squashed everywhere, like a spider or an earthworm. In fact, for academic men to be happy, the universe would have to take shape. All of philosophy has no other goal: it is a matter of giving a frock coat to what is, a mathematical frock coat. On the other hand, affirming that the universe resembles nothing and is only formless amounts to saying that the universe is something like a spider or spit.

A dictionary begins when it no longer gives the meaning of words, but their tasks. Thus formless is not only an adjective having a given meaning, but a term that serves to bring things down in the world, generally requiring that each thing have its form. What it designates has no rights in any sense and gets itself squashed everywhere, like a spider or an earthworm. In fact, for academic men to be happy, the universe would have to take shape. All of philosophy has no other goal: it is a matter of giving a frock coat to what is, a mathematical frock coat. On the other hand, affirming that the universe resembles nothing and is only formless amounts to saying that the universe is something like a spider or spit.

A dictionary begins when it no longer gives the meaning of words, but their tasks. Thus formless is not only an adjective having a given meaning, but a term that serves to bring things down in the world, generally requiring that each thing have its form. What it designates has no rights in any sense and gets itself squashed everywhere, like a spider or an earthworm. In fact, for academic men to be happy, the universe would have to take shape. All of philosophy has no other goal: it is a matter of giving a frock coat to what is, a mathematical frock coat. On the other hand, affirming that the universe resembles nothing and is only formless amounts to saying that the universe is something like a spider or spit.

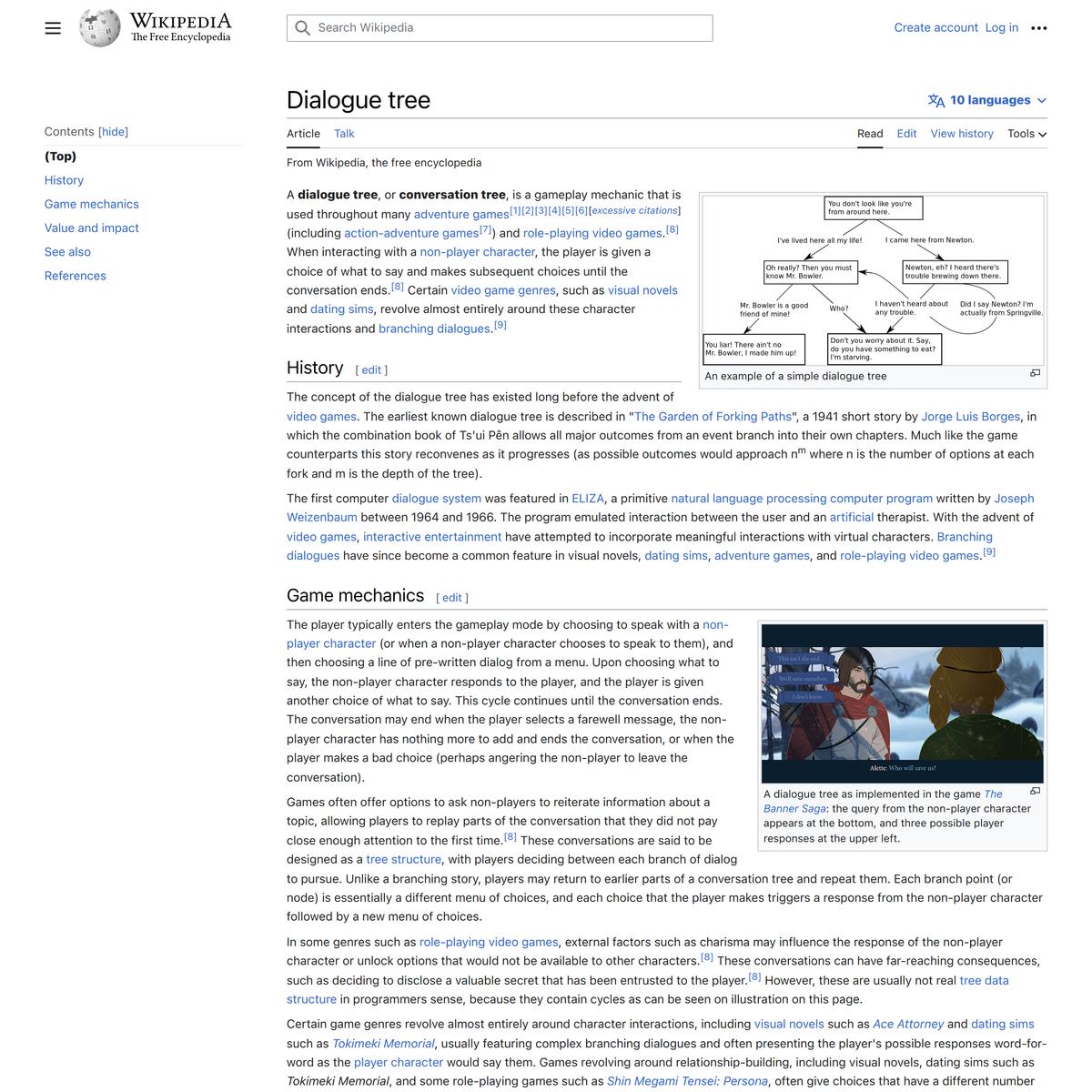

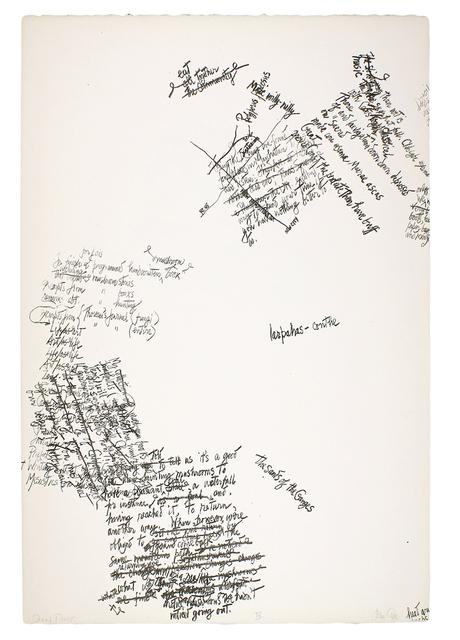

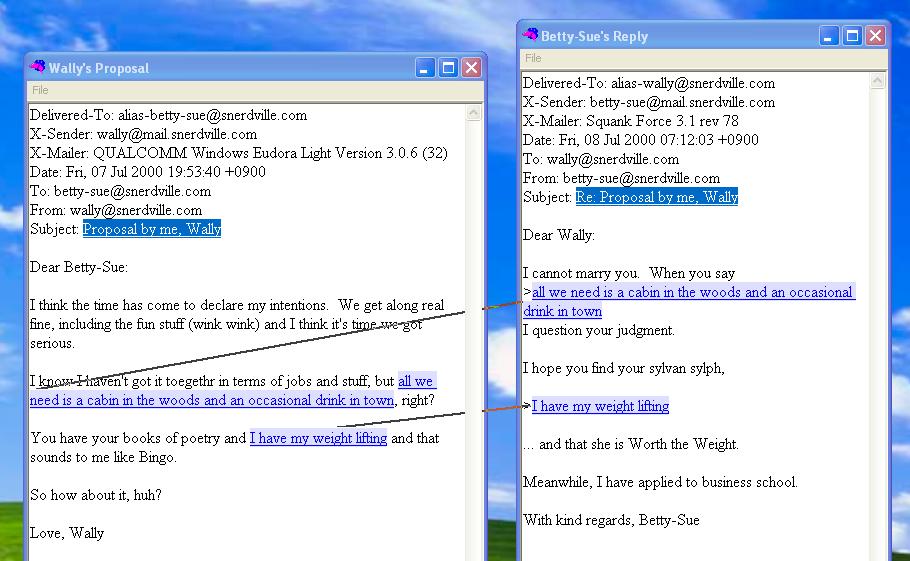

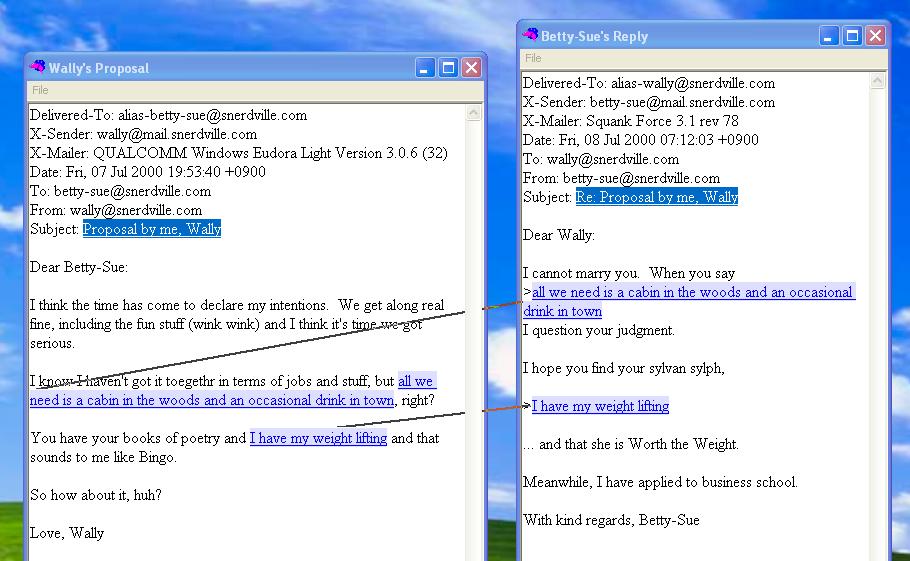

What is a parenthesis but an idea trying to escape? What is a footnote but an idea that jumped off the cliff?

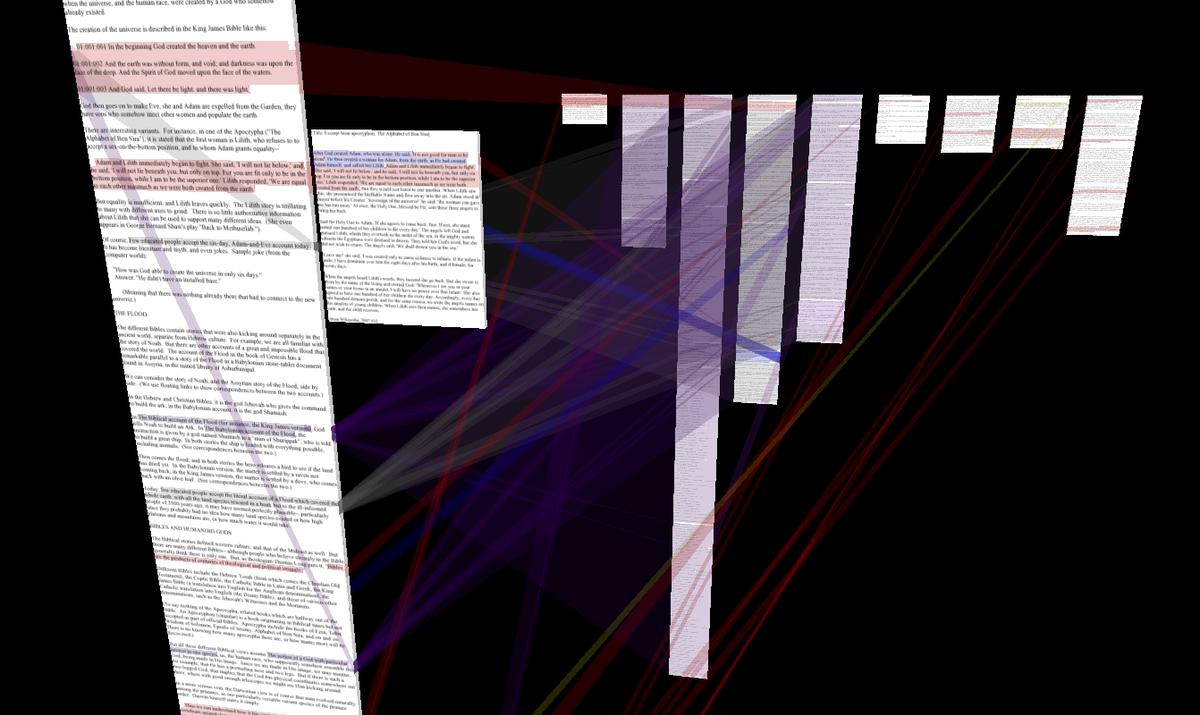

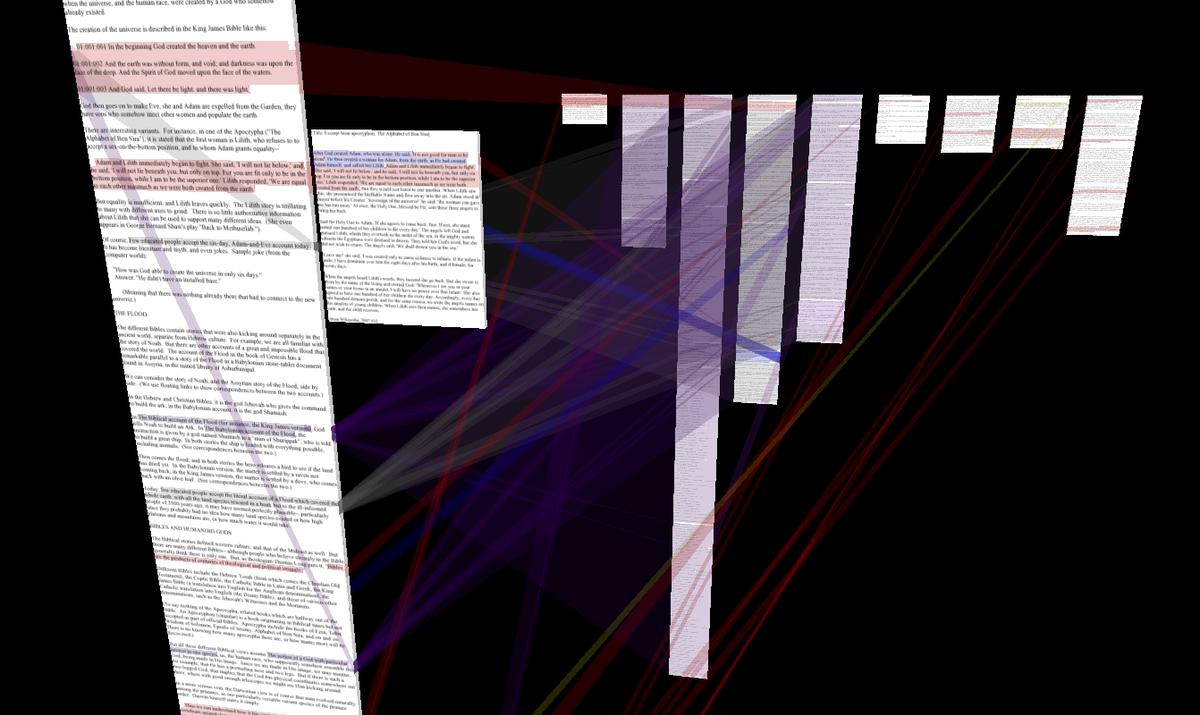

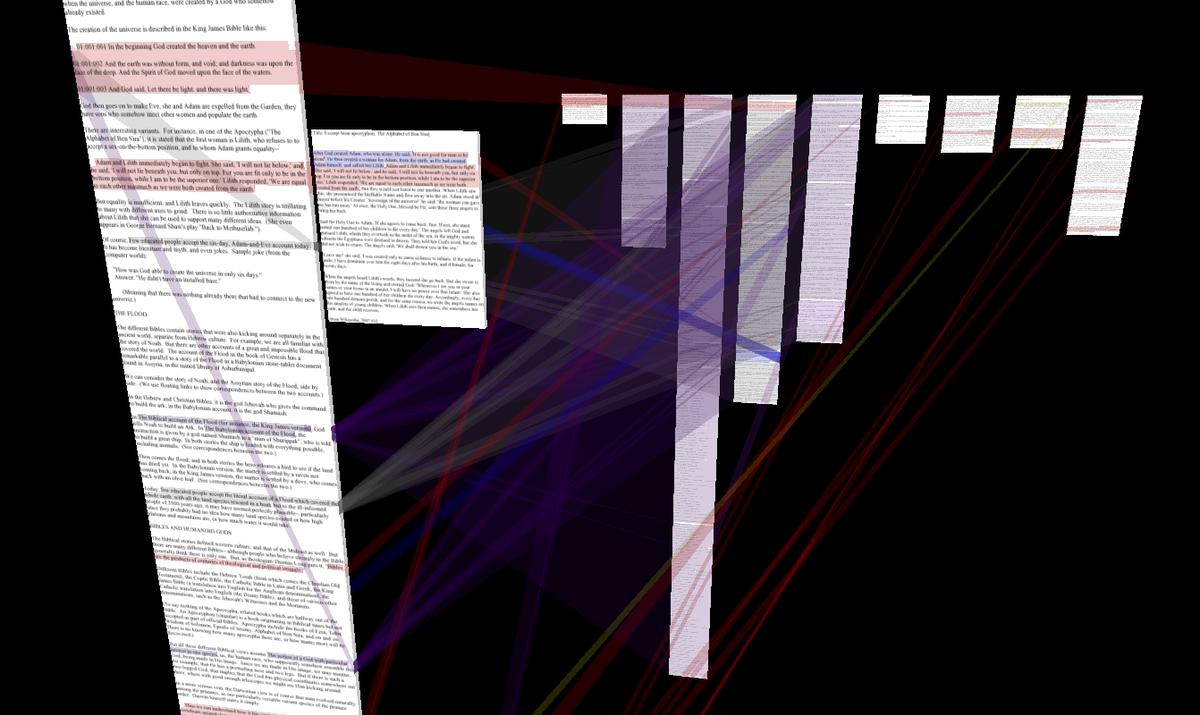

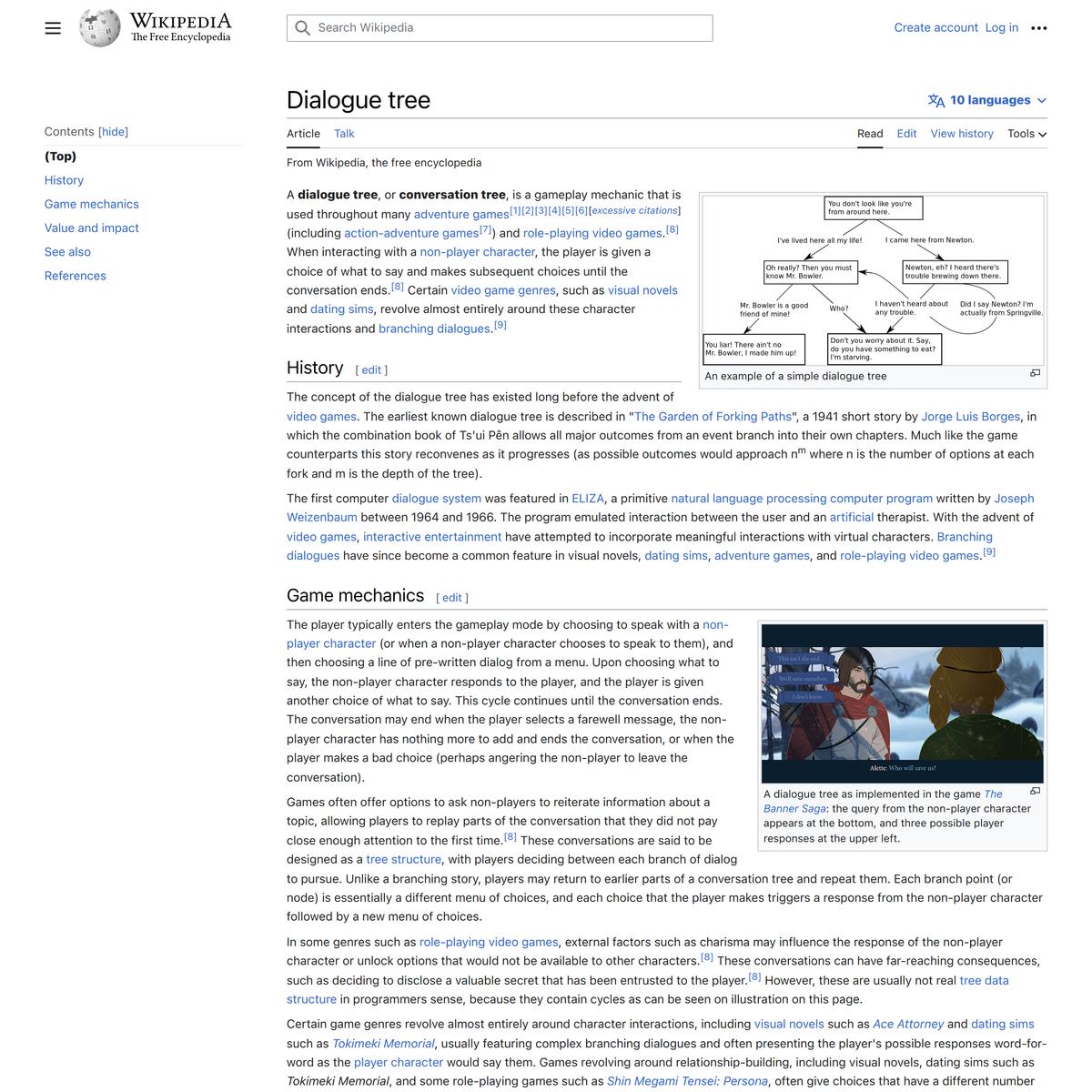

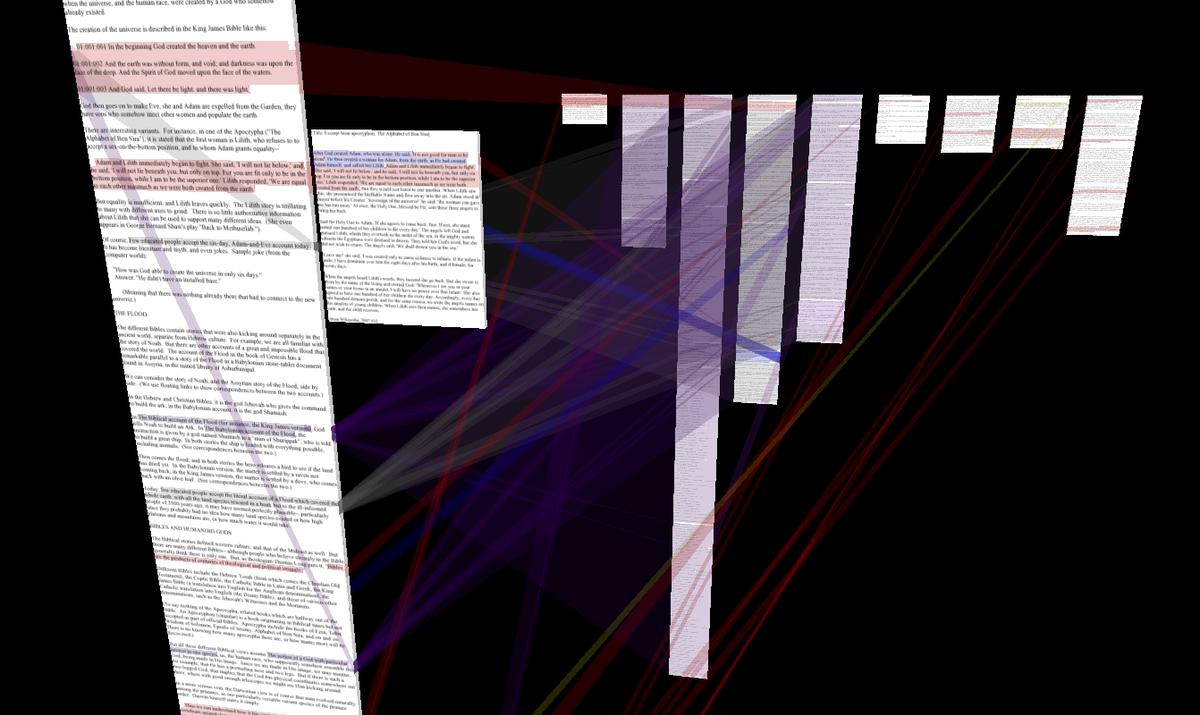

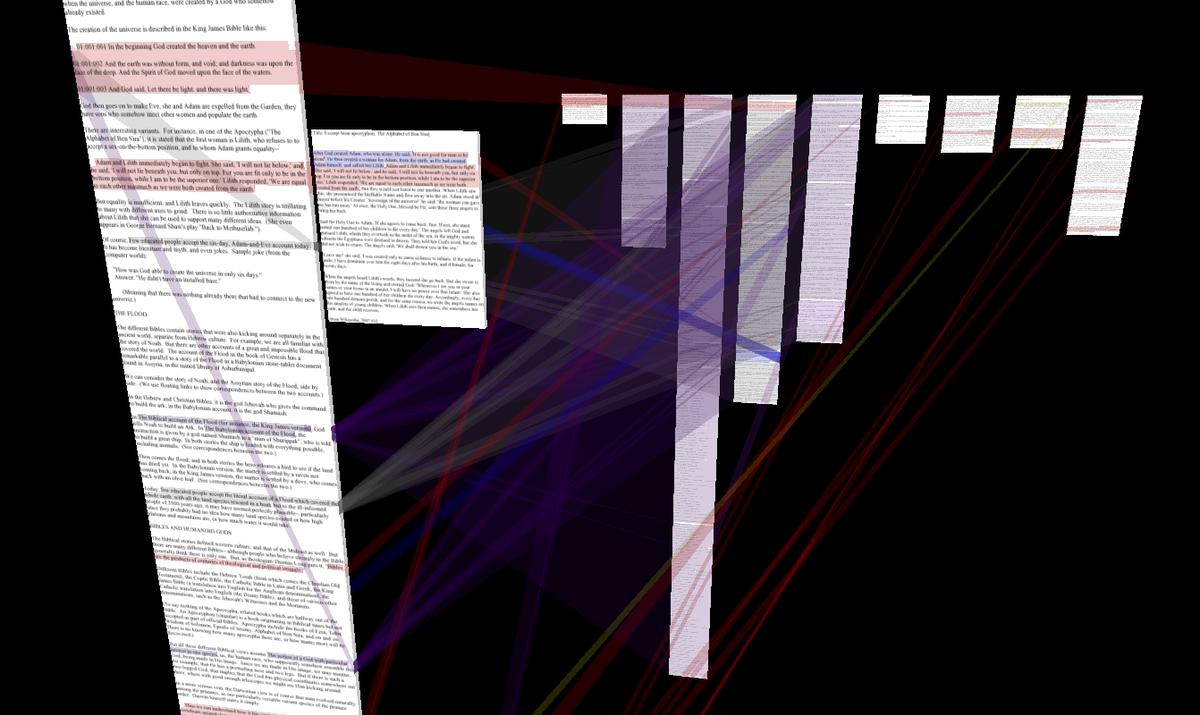

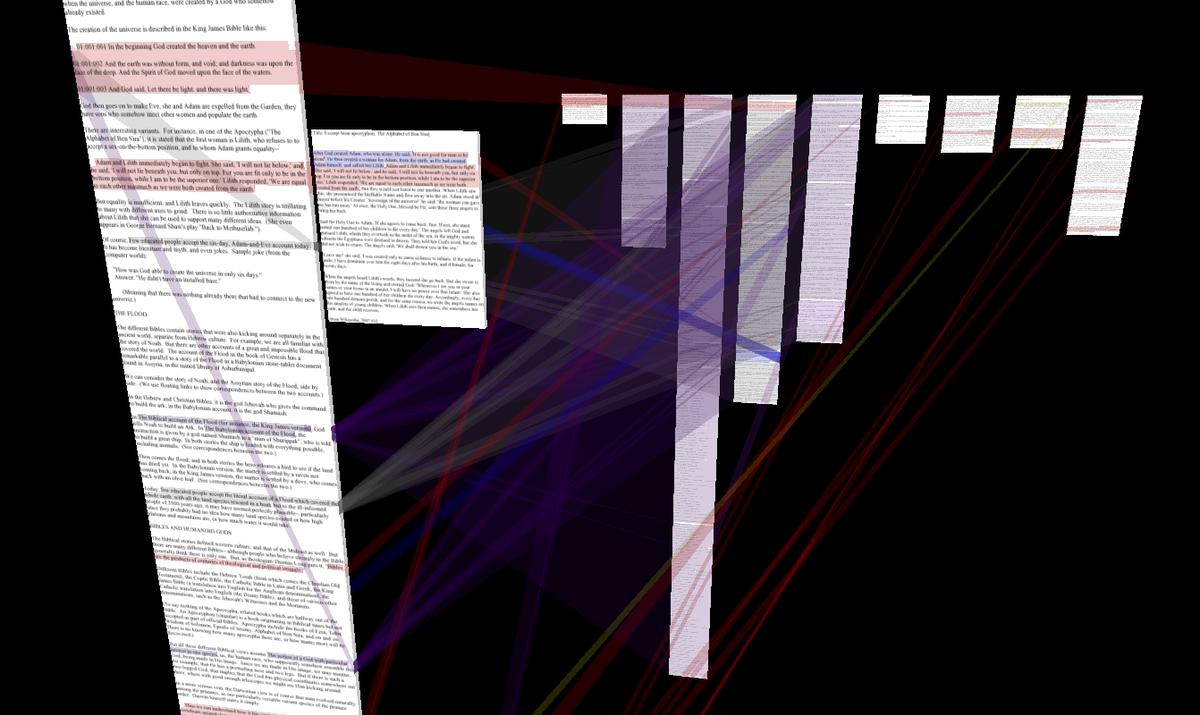

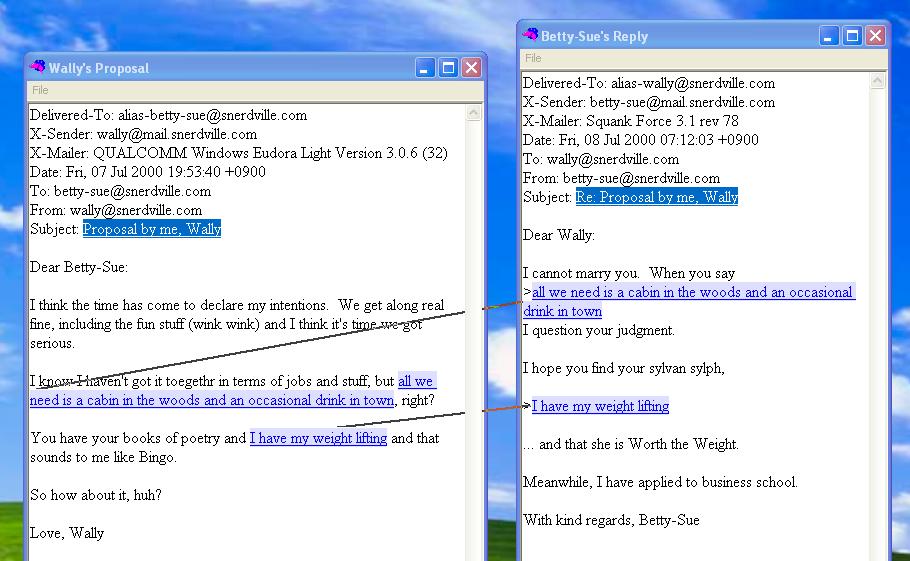

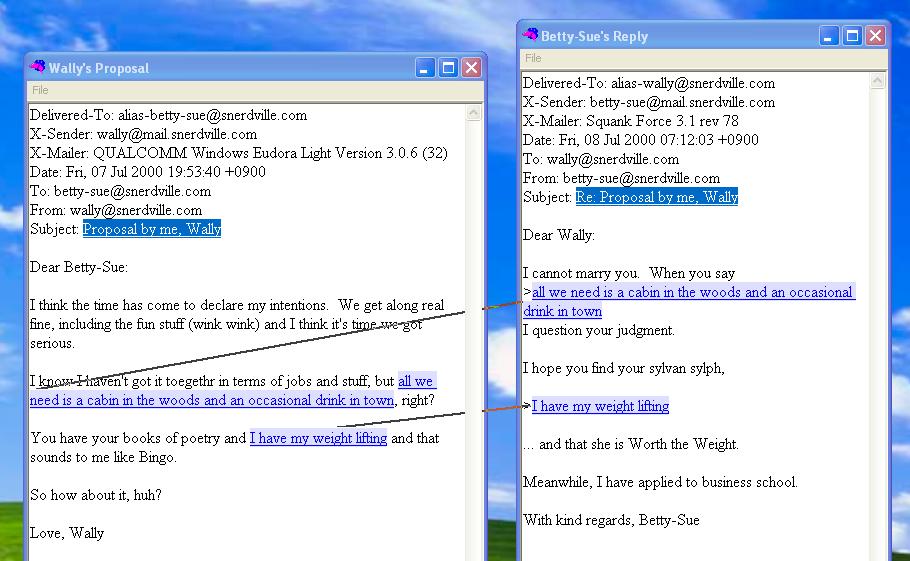

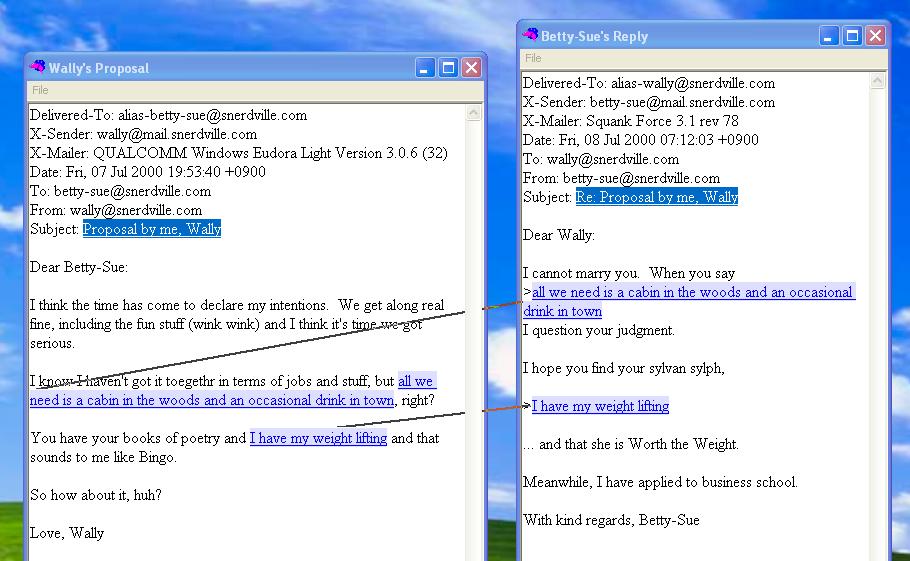

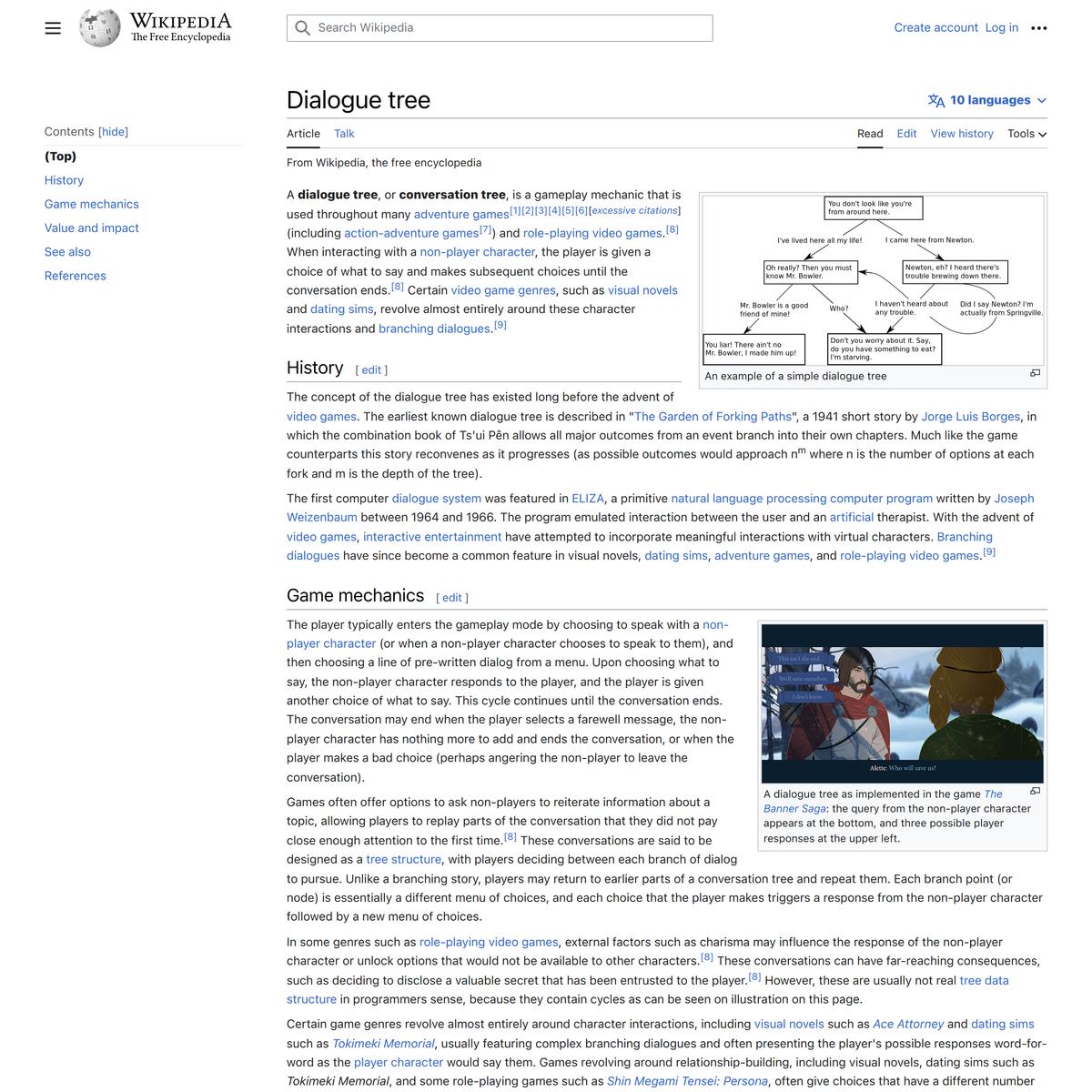

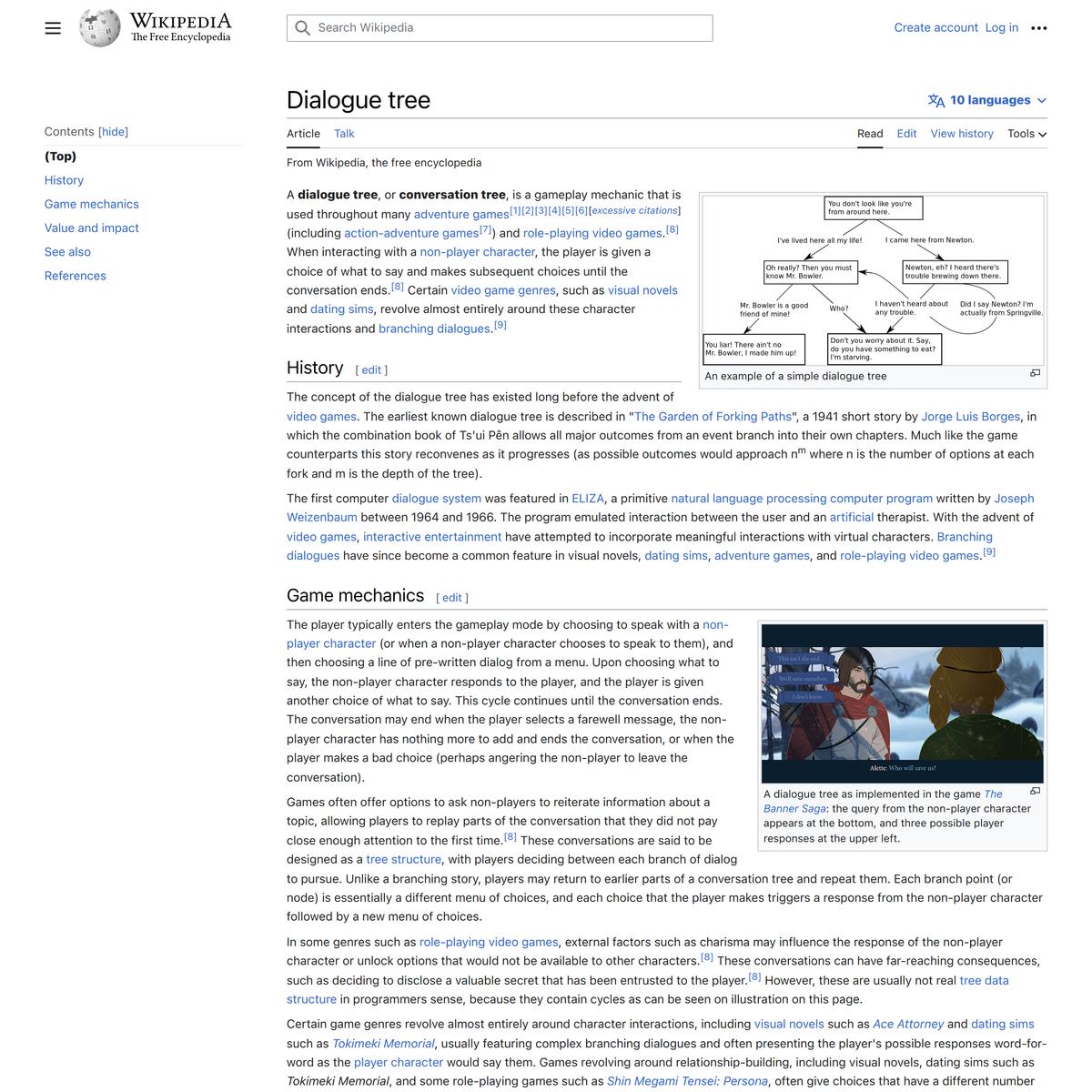

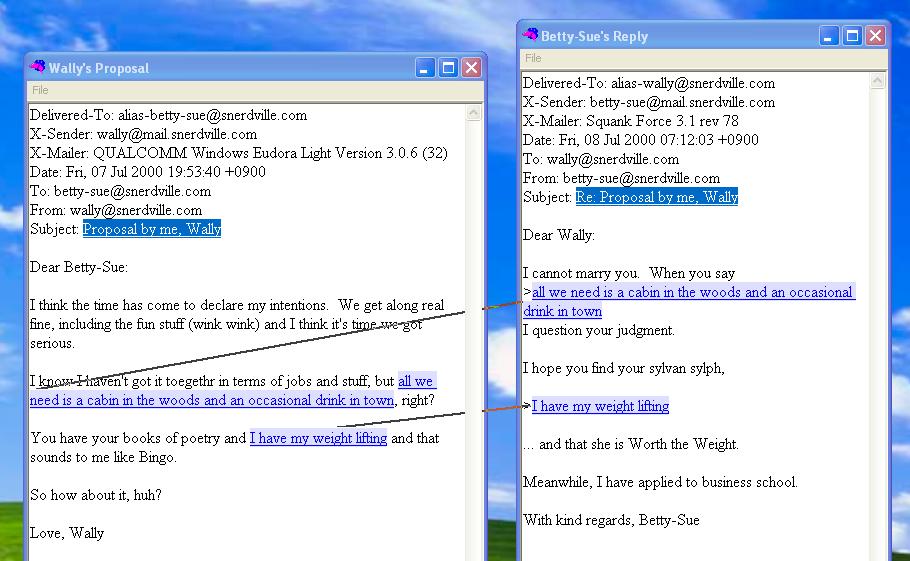

Paper enforces single sequence and there's no room for digression. It imposes a particular kind of order in the very nature of the structure. When I saw the computer I said, "at last we can escape from the prison of paper!" [...] Contrarily, what did the other people do? They imitated paper.

[...] What do you want in electronic documents that is not possible on paper? Well, for one thing, parallelism. You want things [marginal notes, deep links, origins of content] on the side. [...] Consider the writing of history. What is history? It's many parallel streams of events which meet at certain points. So why not create them as parallel structures that makes it easier to write, easy to read. [...]

The techies have imitated the conventional media of the past [...] Why, when we could have movies that branch and branch and branch forever and keep track of them? This is a radical proposal for a completely new different system of media and representing each user as a simultaneous reader and writer, which is what we really are.

What is a parenthesis but an idea trying to escape? What is a footnote but an idea that jumped off the cliff?

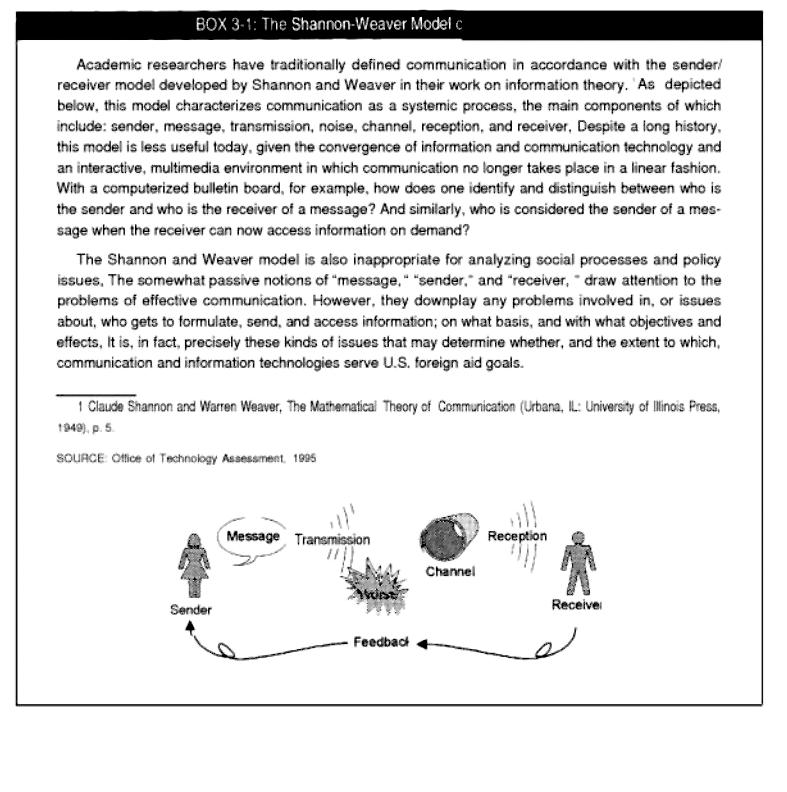

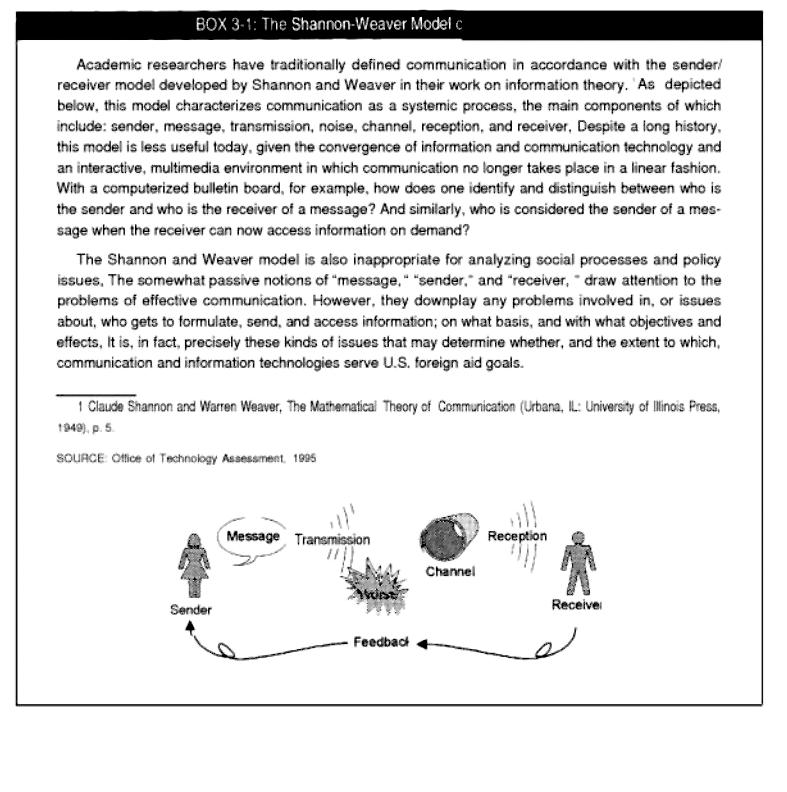

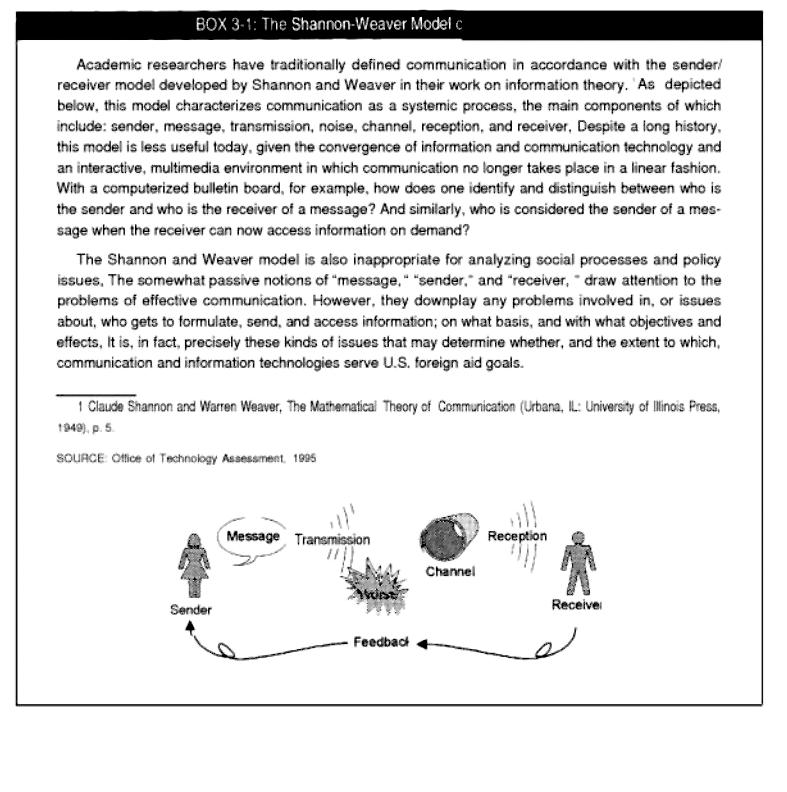

Paper enforces single sequence and there's no room for digression. It imposes a particular kind of order in the very nature of the structure. When I saw the computer I said, "at last we can escape from the prison of paper!" [...] Contrarily, what did the other people do? They imitated paper.

[...] What do you want in electronic documents that is not possible on paper? Well, for one thing, parallelism. You want things [marginal notes, deep links, origins of content] on the side. [...] Consider the writing of history. What is history? It's many parallel streams of events which meet at certain points. So why not create them as parallel structures that makes it easier to write, easy to read. [...]

The techies have imitated the conventional media of the past [...] Why, when we could have movies that branch and branch and branch forever and keep track of them? This is a radical proposal for a completely new different system of media and representing each user as a simultaneous reader and writer, which is what we really are.

What is a parenthesis but an idea trying to escape? What is a footnote but an idea that jumped off the cliff?

Paper enforces single sequence and there's no room for digression. It imposes a particular kind of order in the very nature of the structure. When I saw the computer I said, "at last we can escape from the prison of paper!" [...] Contrarily, what did the other people do? They imitated paper.

[...] What do you want in electronic documents that is not possible on paper? Well, for one thing, parallelism. You want things [marginal notes, deep links, origins of content] on the side. [...] Consider the writing of history. What is history? It's many parallel streams of events which meet at certain points. So why not create them as parallel structures that makes it easier to write, easy to read. [...]

The techies have imitated the conventional media of the past [...] Why, when we could have movies that branch and branch and branch forever and keep track of them? This is a radical proposal for a completely new different system of media and representing each user as a simultaneous reader and writer, which is what we really are.

I was struck by that error, nolle and noli. Our organism of language mutates. It gets things wrong, by transcription or misunderstanding. Notice even this little clump of sentences that I’ve written: I’ve tried to respect Heaney, the ambiguity of his experience, the mourning ache of his family. (Is it an ache? Is such a word accurate? I don’t know.) But I’ve written about it all the same, and in doing so I have translated it.

I was struck by that error, nolle and noli. Our organism of language mutates. It gets things wrong, by transcription or misunderstanding. Notice even this little clump of sentences that I’ve written: I’ve tried to respect Heaney, the ambiguity of his experience, the mourning ache of his family. (Is it an ache? Is such a word accurate? I don’t know.) But I’ve written about it all the same, and in doing so I have translated it.

I was struck by that error, nolle and noli. Our organism of language mutates. It gets things wrong, by transcription or misunderstanding. Notice even this little clump of sentences that I’ve written: I’ve tried to respect Heaney, the ambiguity of his experience, the mourning ache of his family. (Is it an ache? Is such a word accurate? I don’t know.) But I’ve written about it all the same, and in doing so I have translated it.

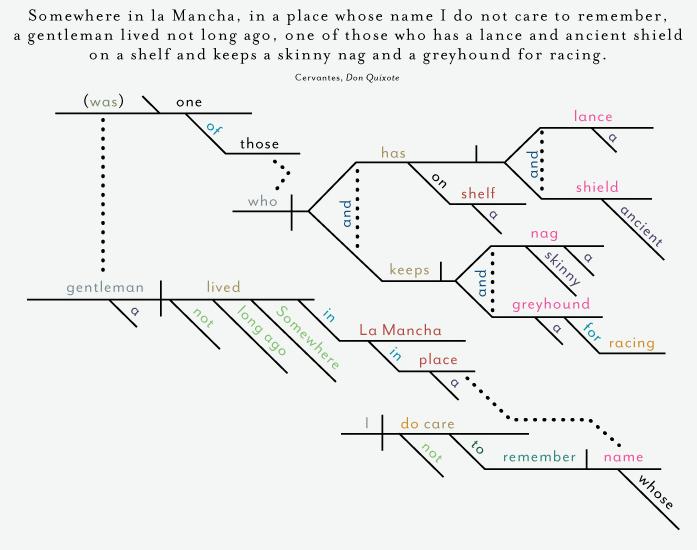

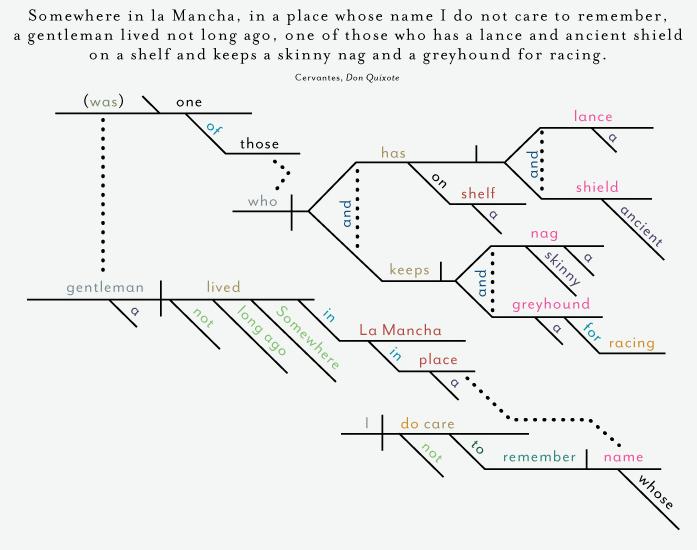

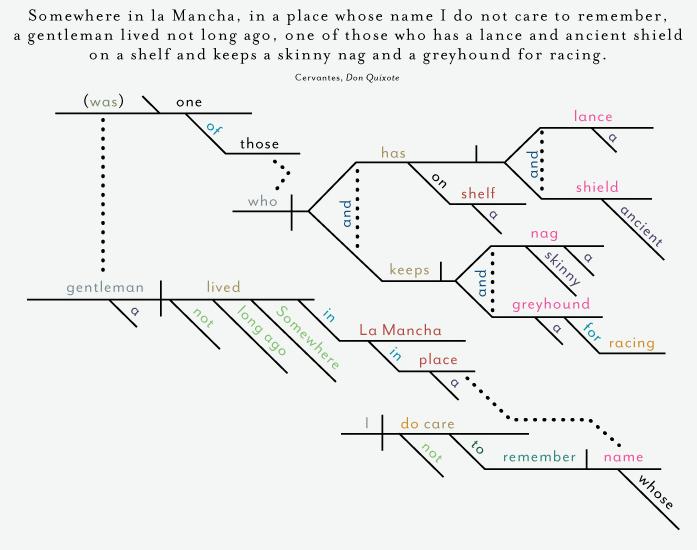

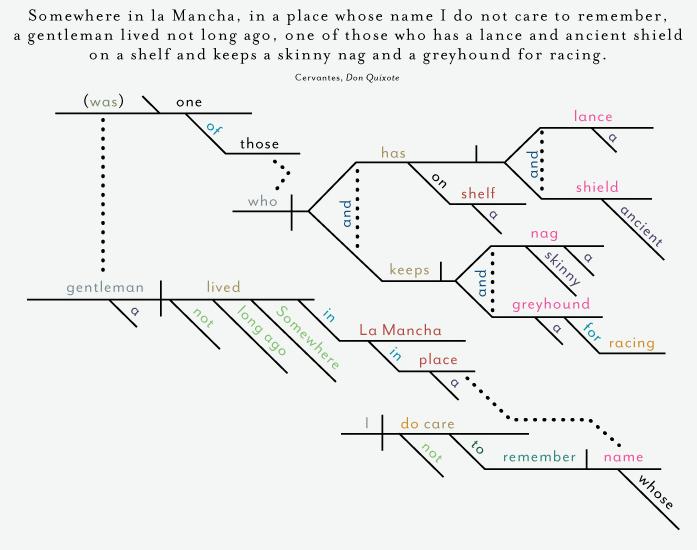

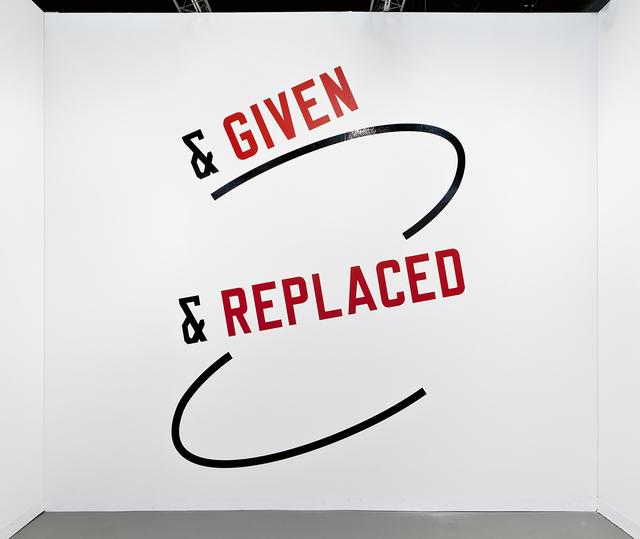

The visible connection becomes a structural part of the writing, as fundamental as a paragraph or heading.

The visible connection becomes a structural part of the writing, as fundamental as a paragraph or heading.

The visible connection becomes a structural part of the writing, as fundamental as a paragraph or heading.

What is a parenthesis but an idea trying to escape? What is a footnote but an idea that jumped off the cliff?

Paper enforces single sequence and there's no room for digression. It imposes a particular kind of order in the very nature of the structure. When I saw the computer I said, "at last we can escape from the prison of paper!" [...] Contrarily, what did the other people do? They imitated paper.

[...] What do you want in electronic documents that is not possible on paper? Well, for one thing, parallelism. You want things [marginal notes, deep links, origins of content] on the side. [...] Consider the writing of history. What is history? It's many parallel streams of events which meet at certain points. So why not create them as parallel structures that makes it easier to write, easy to read. [...]

The techies have imitated the conventional media of the past [...] Why, when we could have movies that branch and branch and branch forever and keep track of them? This is a radical proposal for a completely new different system of media and representing each user as a simultaneous reader and writer, which is what we really are.

What is a parenthesis but an idea trying to escape? What is a footnote but an idea that jumped off the cliff?

Paper enforces single sequence and there's no room for digression. It imposes a particular kind of order in the very nature of the structure. When I saw the computer I said, "at last we can escape from the prison of paper!" [...] Contrarily, what did the other people do? They imitated paper.

[...] What do you want in electronic documents that is not possible on paper? Well, for one thing, parallelism. You want things [marginal notes, deep links, origins of content] on the side. [...] Consider the writing of history. What is history? It's many parallel streams of events which meet at certain points. So why not create them as parallel structures that makes it easier to write, easy to read. [...]

The techies have imitated the conventional media of the past [...] Why, when we could have movies that branch and branch and branch forever and keep track of them? This is a radical proposal for a completely new different system of media and representing each user as a simultaneous reader and writer, which is what we really are.

What is a parenthesis but an idea trying to escape? What is a footnote but an idea that jumped off the cliff?

Paper enforces single sequence and there's no room for digression. It imposes a particular kind of order in the very nature of the structure. When I saw the computer I said, "at last we can escape from the prison of paper!" [...] Contrarily, what did the other people do? They imitated paper.

[...] What do you want in electronic documents that is not possible on paper? Well, for one thing, parallelism. You want things [marginal notes, deep links, origins of content] on the side. [...] Consider the writing of history. What is history? It's many parallel streams of events which meet at certain points. So why not create them as parallel structures that makes it easier to write, easy to read. [...]

The techies have imitated the conventional media of the past [...] Why, when we could have movies that branch and branch and branch forever and keep track of them? This is a radical proposal for a completely new different system of media and representing each user as a simultaneous reader and writer, which is what we really are.

A dictionary begins when it no longer gives the meaning of words, but their tasks. Thus formless is not only an adjective having a given meaning, but a term that serves to bring things down in the world, generally requiring that each thing have its form. What it designates has no rights in any sense and gets itself squashed everywhere, like a spider or an earthworm. In fact, for academic men to be happy, the universe would have to take shape. All of philosophy has no other goal: it is a matter of giving a frock coat to what is, a mathematical frock coat. On the other hand, affirming that the universe resembles nothing and is only formless amounts to saying that the universe is something like a spider or spit.

A dictionary begins when it no longer gives the meaning of words, but their tasks. Thus formless is not only an adjective having a given meaning, but a term that serves to bring things down in the world, generally requiring that each thing have its form. What it designates has no rights in any sense and gets itself squashed everywhere, like a spider or an earthworm. In fact, for academic men to be happy, the universe would have to take shape. All of philosophy has no other goal: it is a matter of giving a frock coat to what is, a mathematical frock coat. On the other hand, affirming that the universe resembles nothing and is only formless amounts to saying that the universe is something like a spider or spit.

A dictionary begins when it no longer gives the meaning of words, but their tasks. Thus formless is not only an adjective having a given meaning, but a term that serves to bring things down in the world, generally requiring that each thing have its form. What it designates has no rights in any sense and gets itself squashed everywhere, like a spider or an earthworm. In fact, for academic men to be happy, the universe would have to take shape. All of philosophy has no other goal: it is a matter of giving a frock coat to what is, a mathematical frock coat. On the other hand, affirming that the universe resembles nothing and is only formless amounts to saying that the universe is something like a spider or spit.

Alfred Korzybski remarked that "the map is not the territory" and that "the word is not the thing", encapsulating his view that an abstraction derived from something, or a reaction to it, is not the thing itself.

Alfred Korzybski remarked that "the map is not the territory" and that "the word is not the thing", encapsulating his view that an abstraction derived from something, or a reaction to it, is not the thing itself.

Alfred Korzybski remarked that "the map is not the territory" and that "the word is not the thing", encapsulating his view that an abstraction derived from something, or a reaction to it, is not the thing itself.

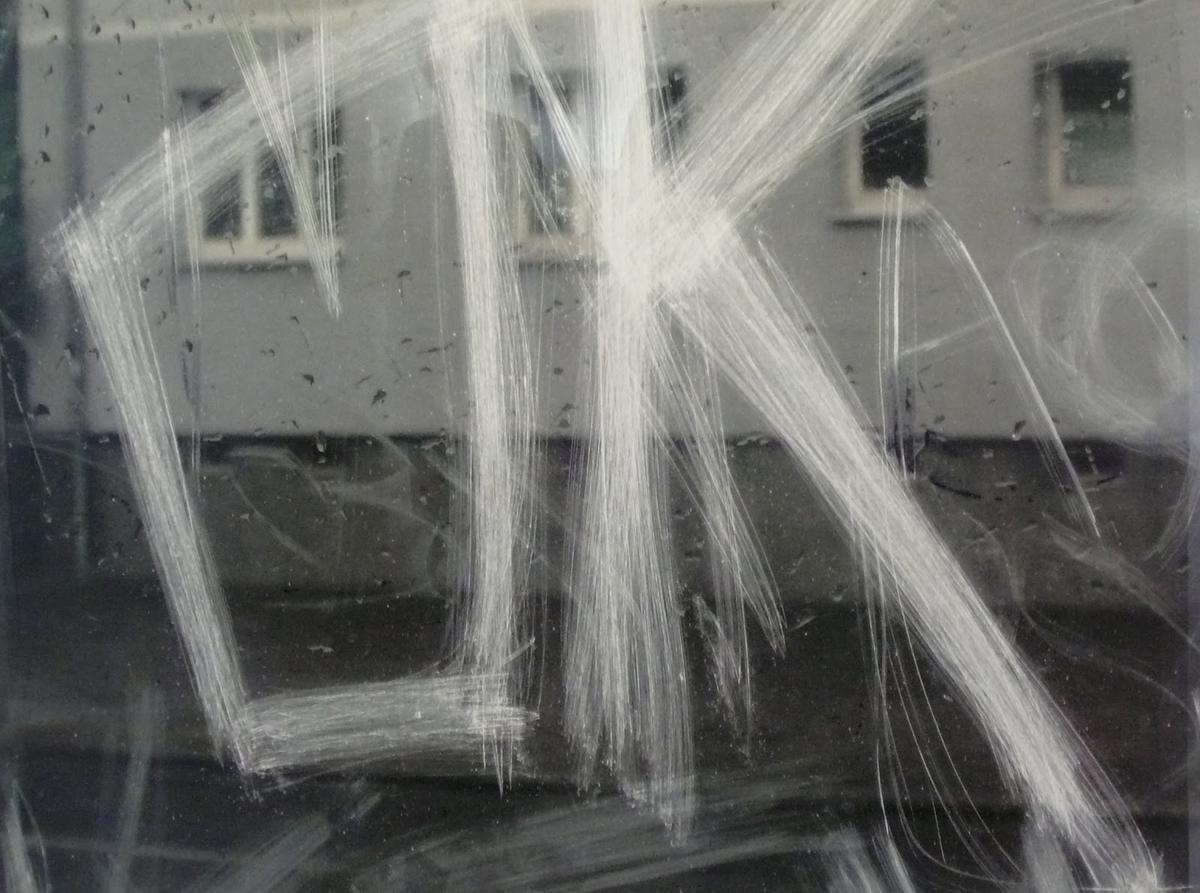

The line is the interface between language and the world. The line is language held taut, and someone has to be doing the work of holding the line taut. [...] Language is always situated in social and physical reality.

The line is the interface between language and the world. The line is language held taut, and someone has to be doing the work of holding the line taut. [...] Language is always situated in social and physical reality.

The line is the interface between language and the world. The line is language held taut, and someone has to be doing the work of holding the line taut. [...] Language is always situated in social and physical reality.

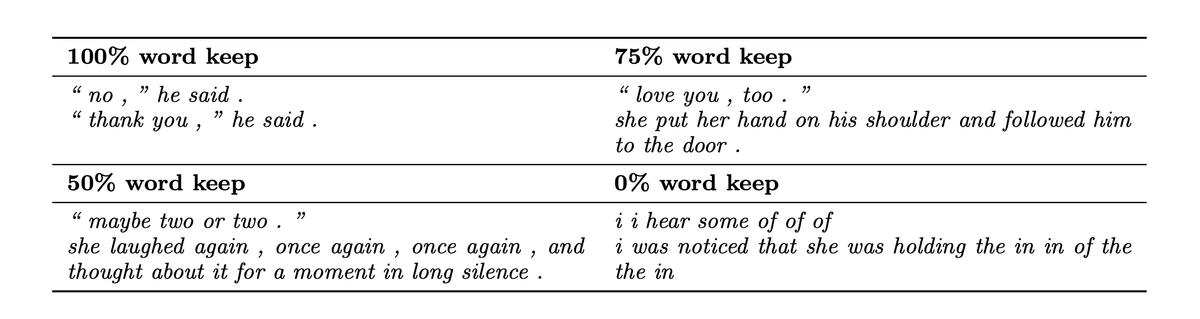

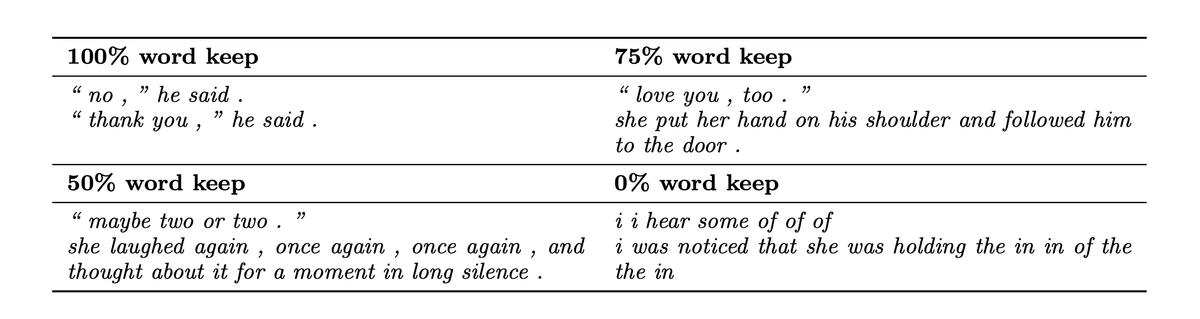

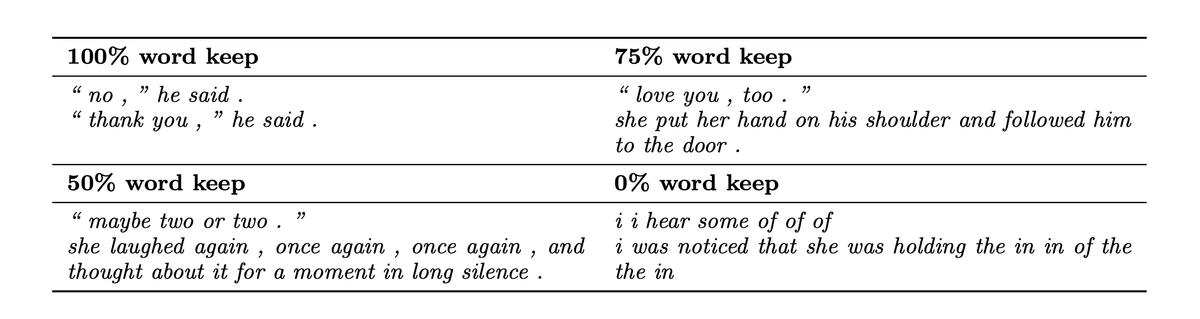

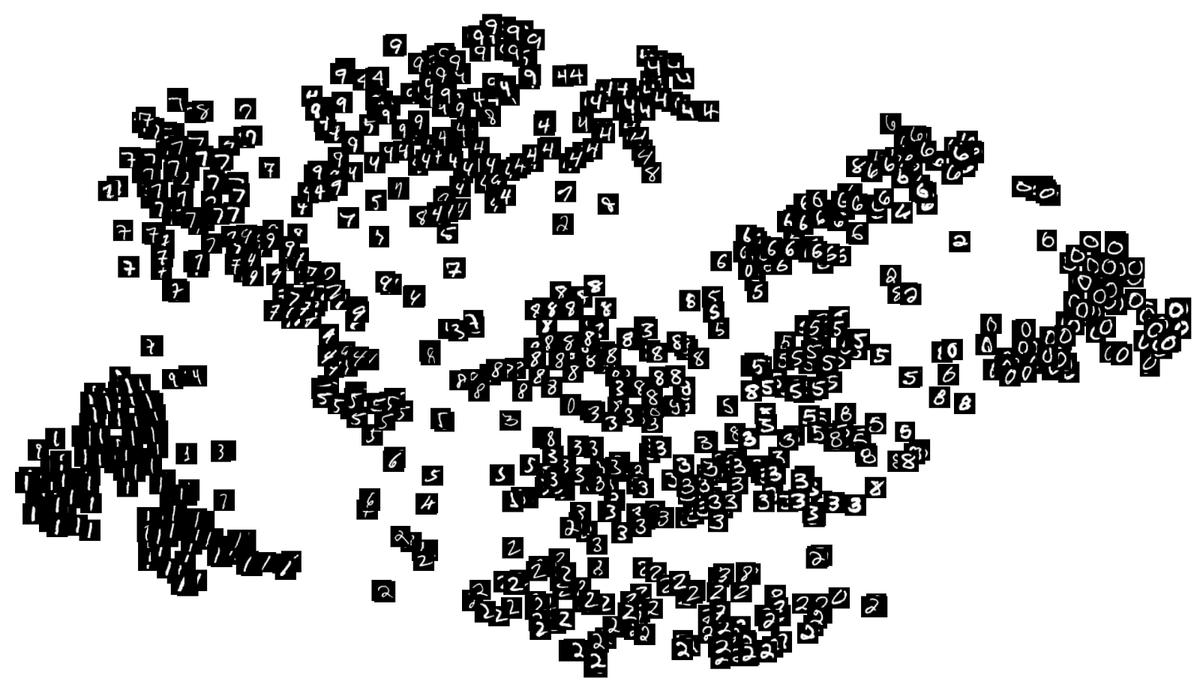

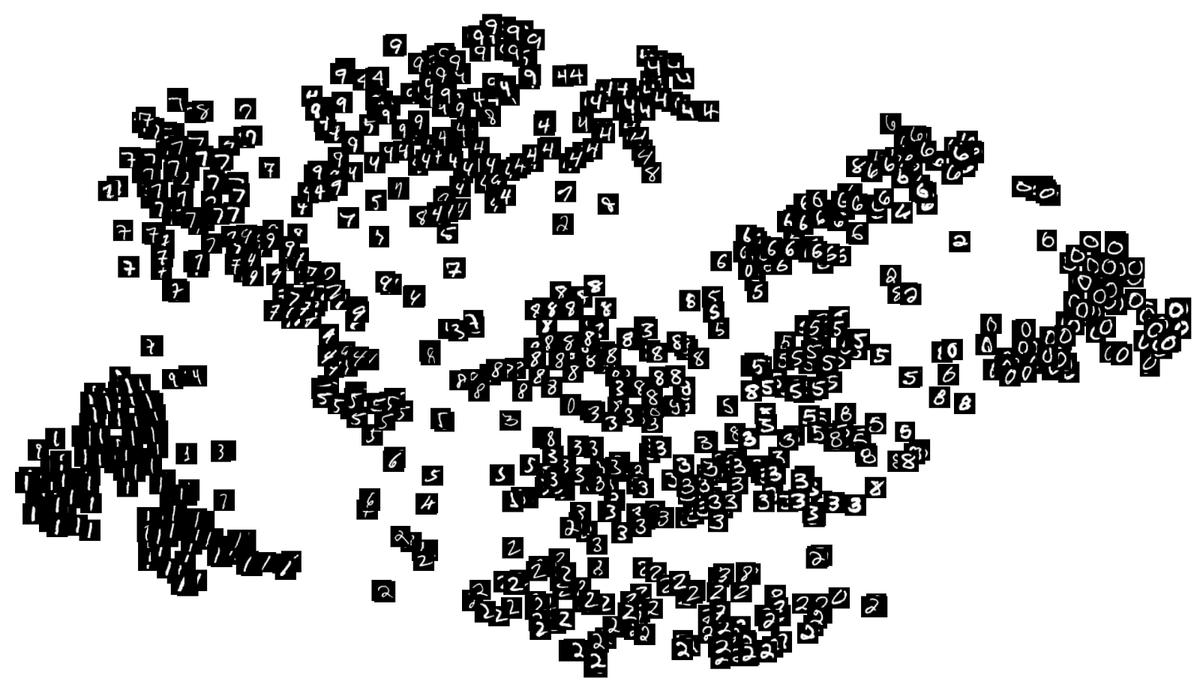

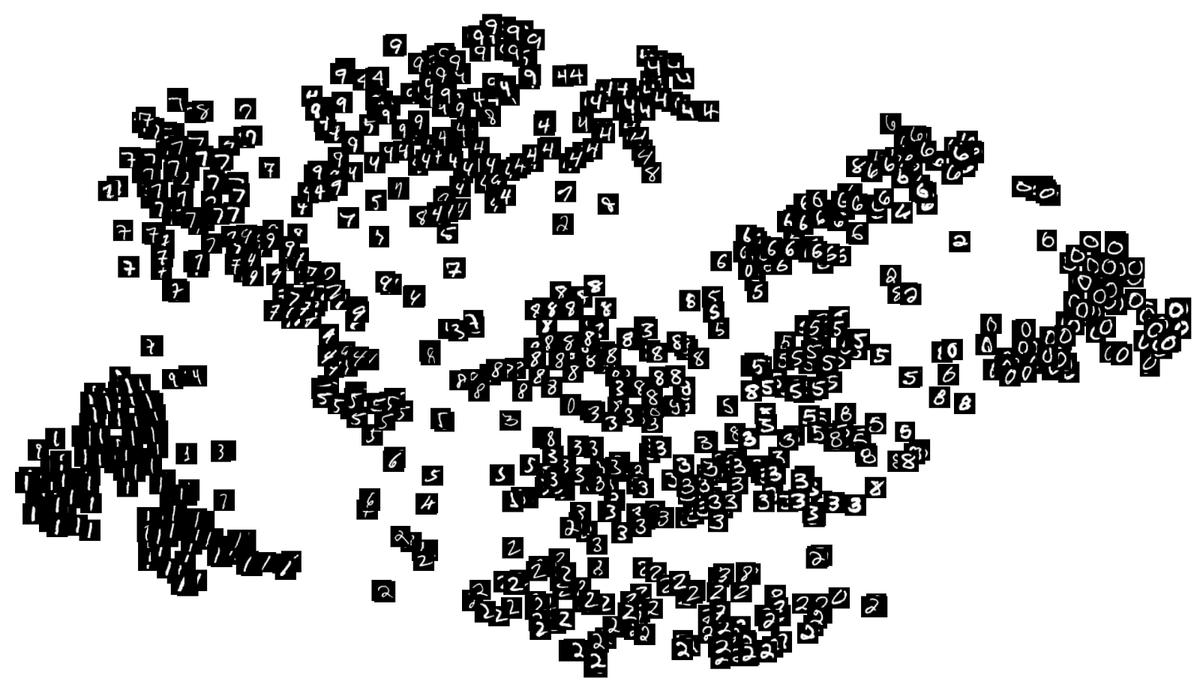

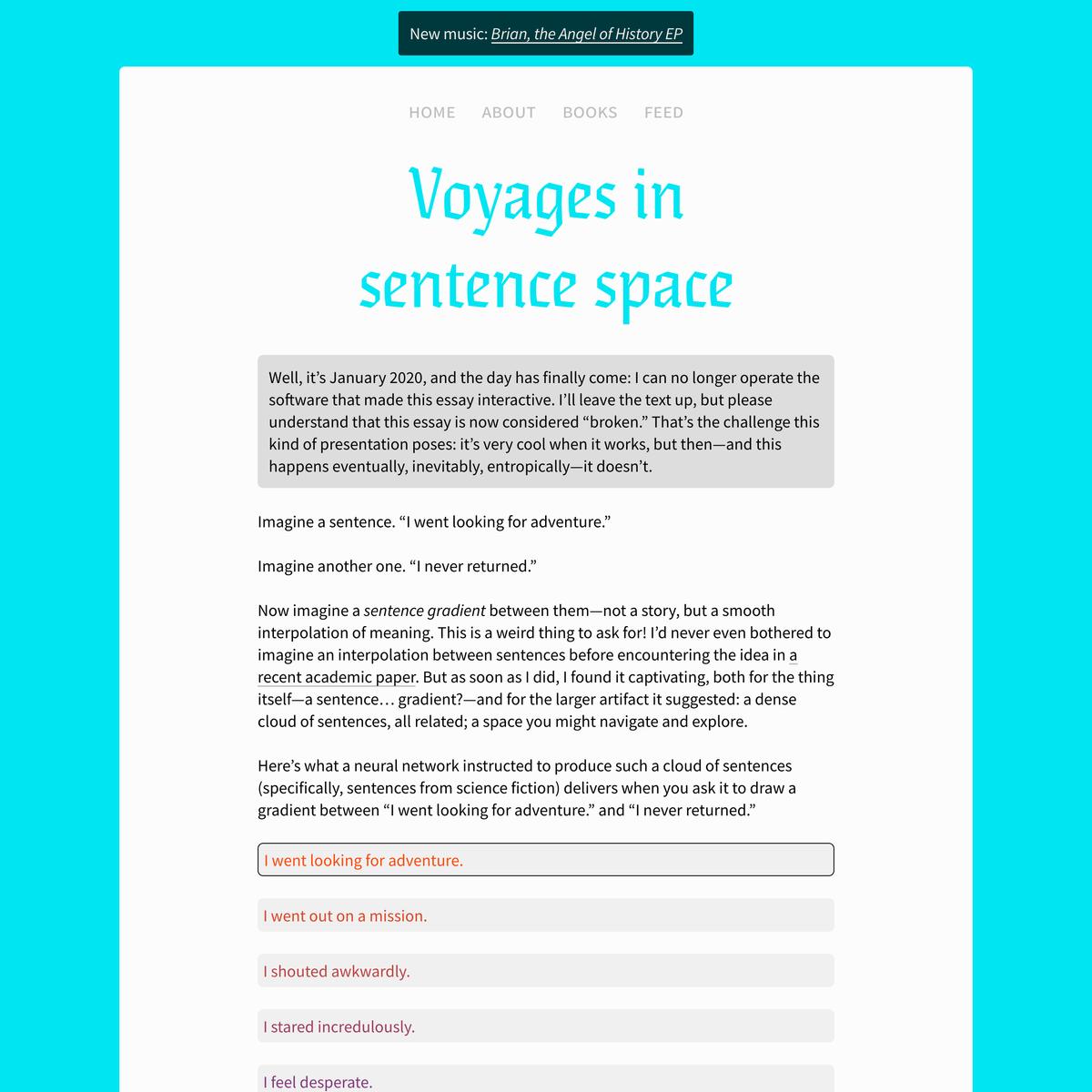

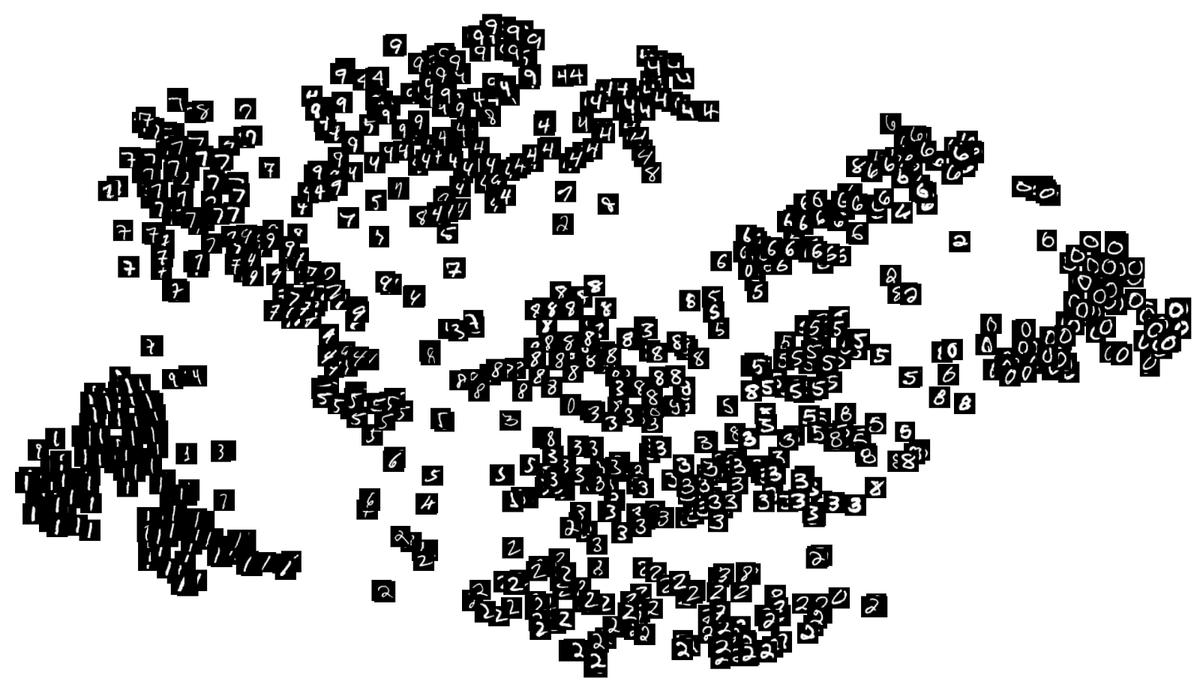

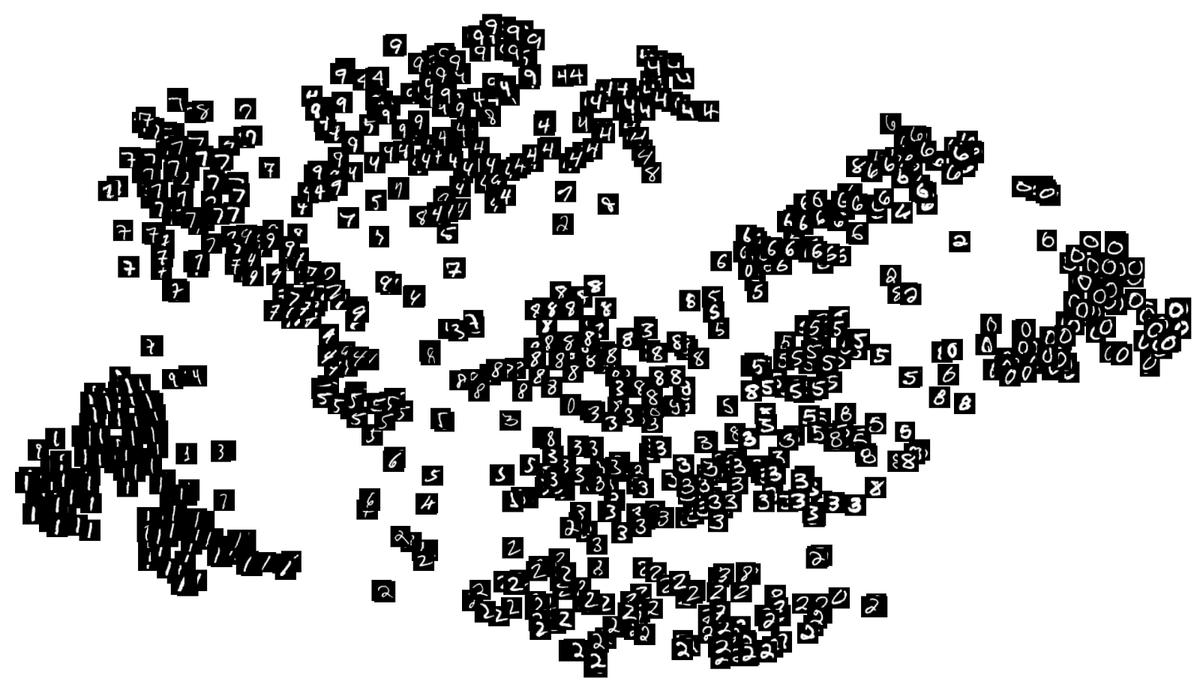

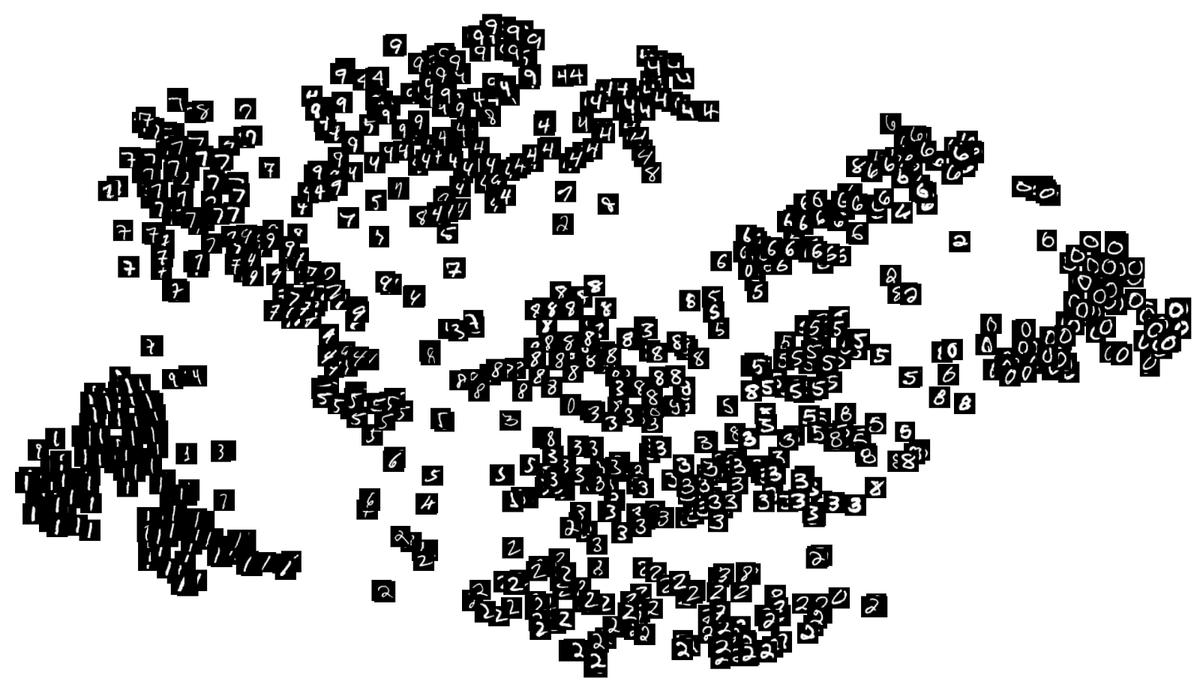

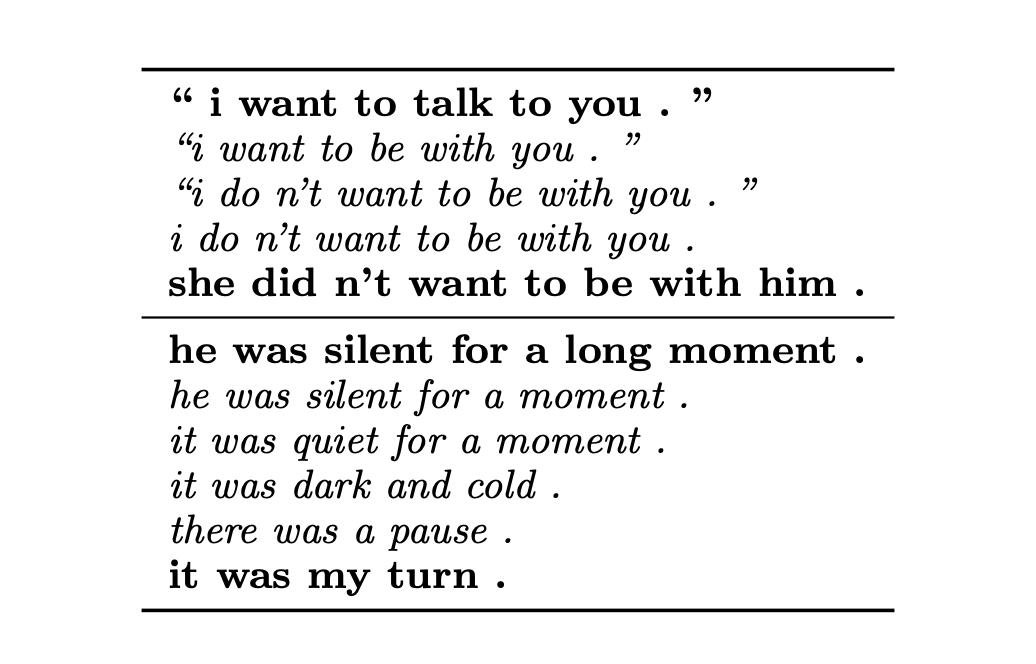

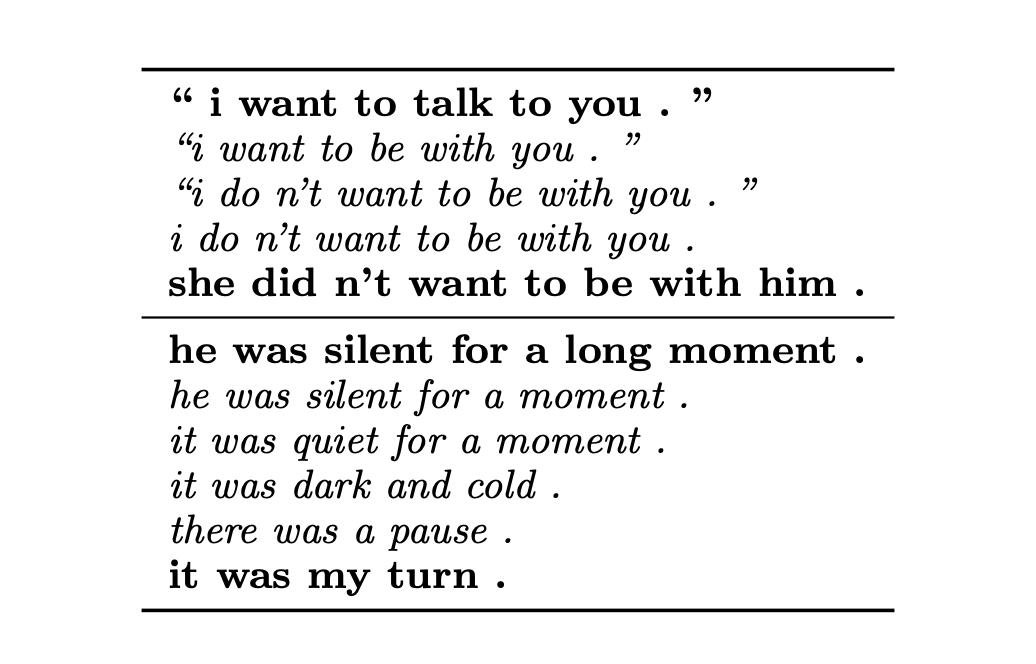

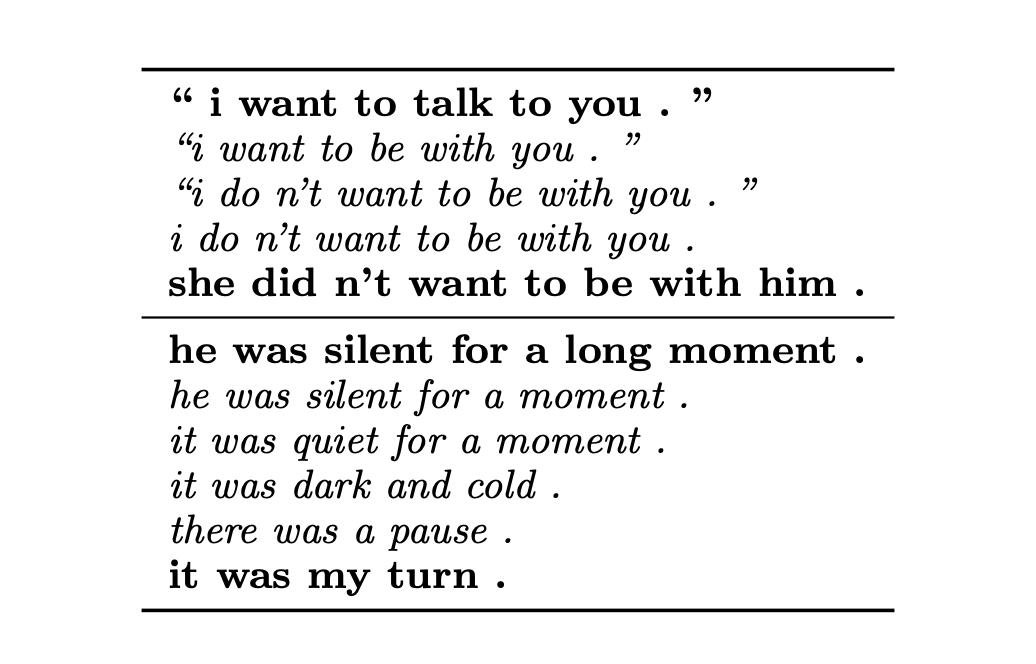

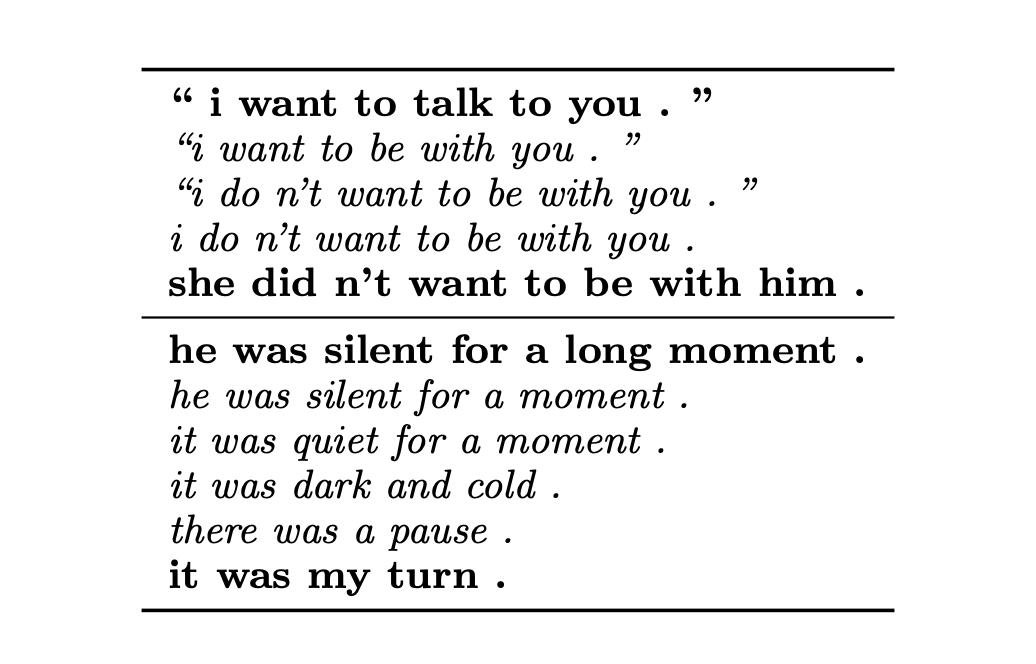

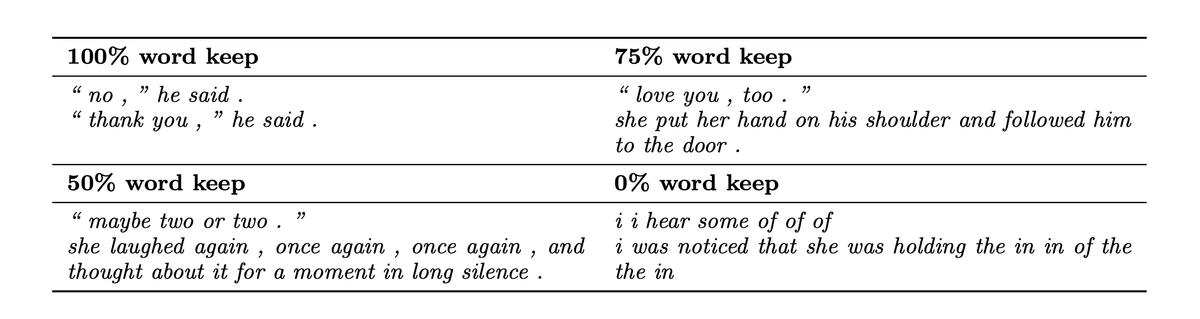

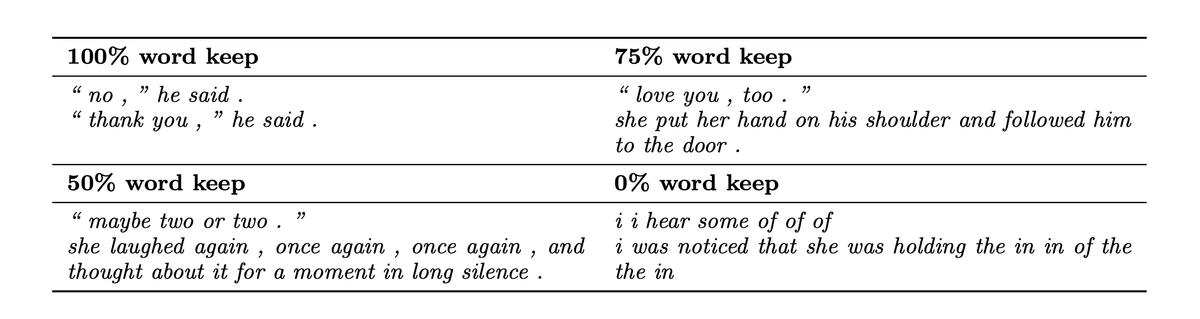

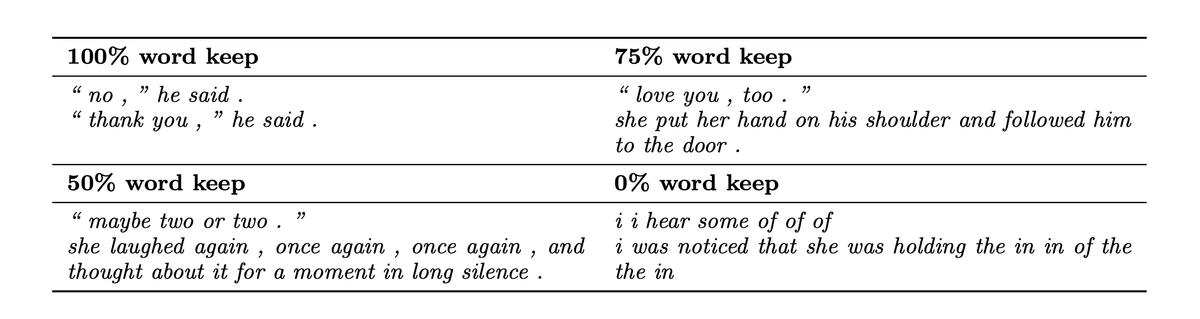

Imagine a sentence. “I went looking for adventure.”

Imagine another one. “I never returned.”

Now imagine a sentence gradient between them—not a story, but a smooth interpolation of meaning. This is a weird thing to ask for! I’d never even bothered to imagine an interpolation between sentences before encountering the idea in a recent academic paper. But as soon as I did, I found it captivating, both for the thing itself—a sentence… gradient?—and for the larger artifact it suggested: a dense cloud of sentences, all related; a space you might navigate and explore.

Imagine a sentence. “I went looking for adventure.”

Imagine another one. “I never returned.”

Now imagine a sentence gradient between them—not a story, but a smooth interpolation of meaning. This is a weird thing to ask for! I’d never even bothered to imagine an interpolation between sentences before encountering the idea in a recent academic paper. But as soon as I did, I found it captivating, both for the thing itself—a sentence… gradient?—and for the larger artifact it suggested: a dense cloud of sentences, all related; a space you might navigate and explore.

Imagine a sentence. “I went looking for adventure.”

Imagine another one. “I never returned.”

Now imagine a sentence gradient between them—not a story, but a smooth interpolation of meaning. This is a weird thing to ask for! I’d never even bothered to imagine an interpolation between sentences before encountering the idea in a recent academic paper. But as soon as I did, I found it captivating, both for the thing itself—a sentence… gradient?—and for the larger artifact it suggested: a dense cloud of sentences, all related; a space you might navigate and explore.

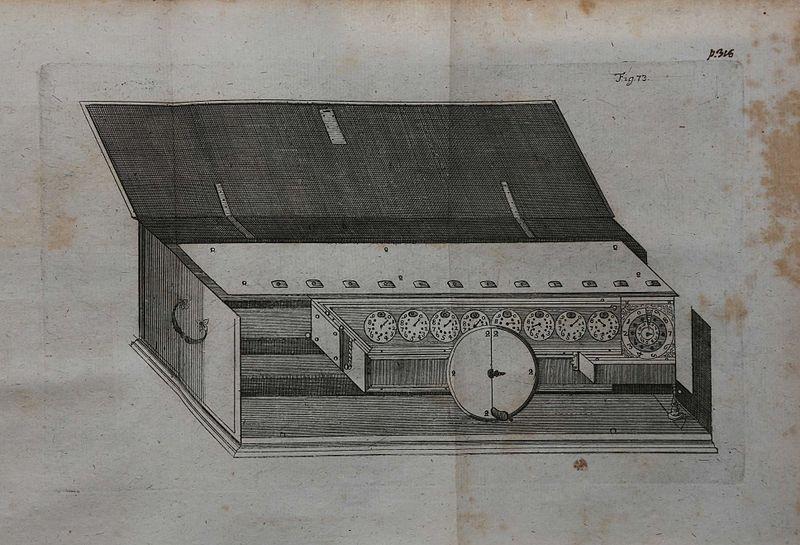

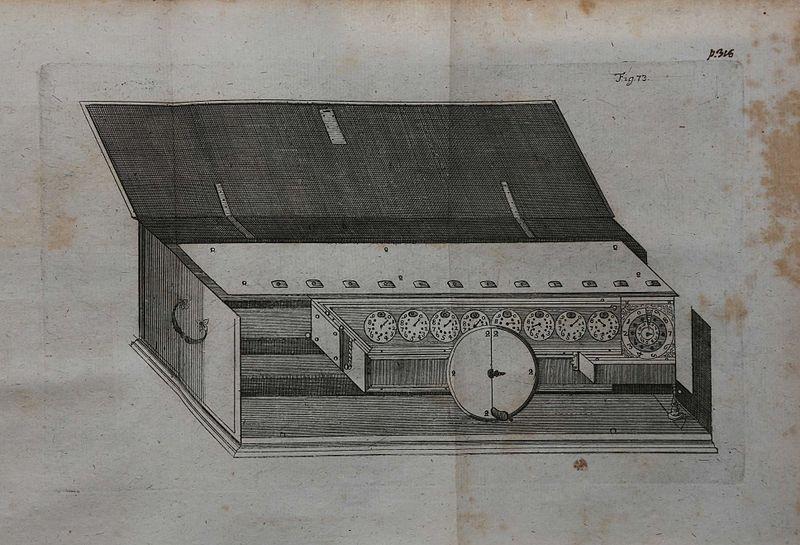

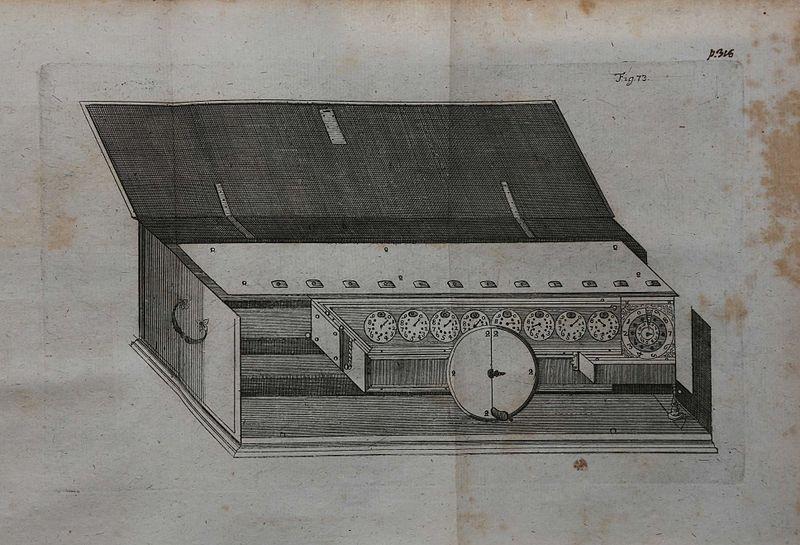

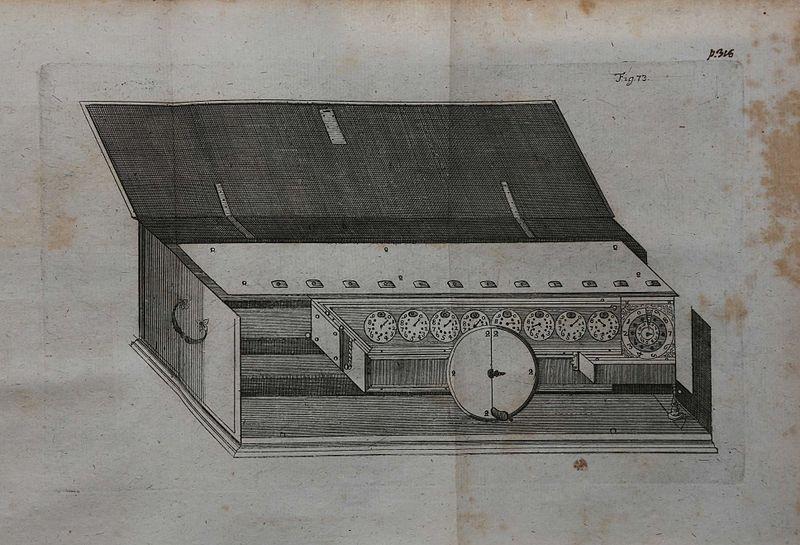

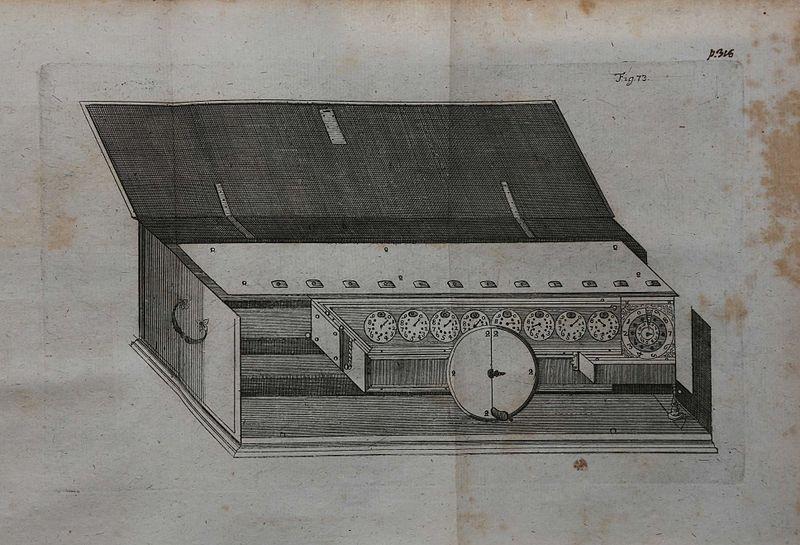

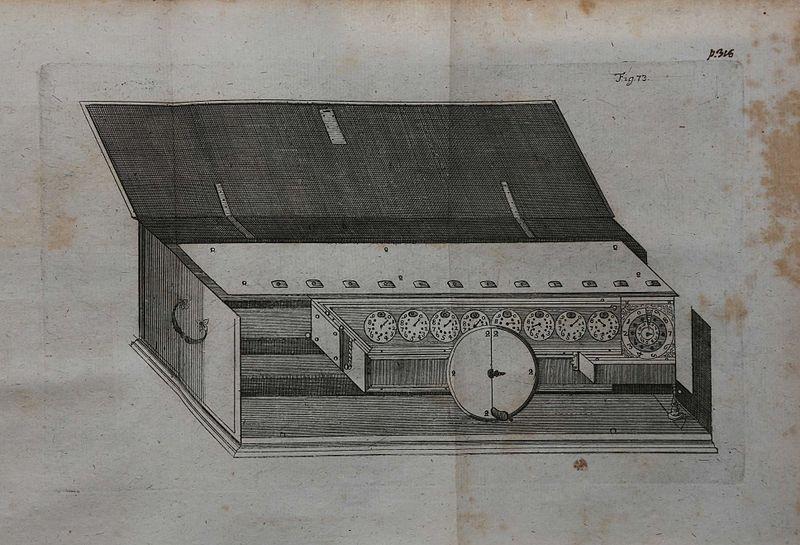

Most of what people call technology is constructs. Artificial, imaginary constructs that people made up. "Directory," "desktop," "game," "spreadsheet" — all imagined constructs that people have dreamed up and implemented in the computer. Today I offer one more construct for your consideration. [...]

Movable type took a lot of technical decisions, like matching the right lead alloy to the right sticky ink mixture, towards the simple construct of the printed book. This project too [Xanadu] has taken a lot of work for a similarly simple literary construct. I've never thought of this as technology, but rather, as what electronic literature ought to be.

Most of what people call technology is constructs. Artificial, imaginary constructs that people made up. "Directory," "desktop," "game," "spreadsheet" — all imagined constructs that people have dreamed up and implemented in the computer. Today I offer one more construct for your consideration. [...]

Movable type took a lot of technical decisions, like matching the right lead alloy to the right sticky ink mixture, towards the simple construct of the printed book. This project too [Xanadu] has taken a lot of work for a similarly simple literary construct. I've never thought of this as technology, but rather, as what electronic literature ought to be.

Most of what people call technology is constructs. Artificial, imaginary constructs that people made up. "Directory," "desktop," "game," "spreadsheet" — all imagined constructs that people have dreamed up and implemented in the computer. Today I offer one more construct for your consideration. [...]

Movable type took a lot of technical decisions, like matching the right lead alloy to the right sticky ink mixture, towards the simple construct of the printed book. This project too [Xanadu] has taken a lot of work for a similarly simple literary construct. I've never thought of this as technology, but rather, as what electronic literature ought to be.

The line is the interface between language and the world. The line is language held taut, and someone has to be doing the work of holding the line taut. [...] Language is always situated in social and physical reality.

The line is the interface between language and the world. The line is language held taut, and someone has to be doing the work of holding the line taut. [...] Language is always situated in social and physical reality.

The line is the interface between language and the world. The line is language held taut, and someone has to be doing the work of holding the line taut. [...] Language is always situated in social and physical reality.

The visible connection becomes a structural part of the writing, as fundamental as a paragraph or heading.

The visible connection becomes a structural part of the writing, as fundamental as a paragraph or heading.

The visible connection becomes a structural part of the writing, as fundamental as a paragraph or heading.

Most of what people call technology is constructs. Artificial, imaginary constructs that people made up. "Directory," "desktop," "game," "spreadsheet" — all imagined constructs that people have dreamed up and implemented in the computer. Today I offer one more construct for your consideration. [...]

Movable type took a lot of technical decisions, like matching the right lead alloy to the right sticky ink mixture, towards the simple construct of the printed book. This project too [Xanadu] has taken a lot of work for a similarly simple literary construct. I've never thought of this as technology, but rather, as what electronic literature ought to be.

Most of what people call technology is constructs. Artificial, imaginary constructs that people made up. "Directory," "desktop," "game," "spreadsheet" — all imagined constructs that people have dreamed up and implemented in the computer. Today I offer one more construct for your consideration. [...]

Movable type took a lot of technical decisions, like matching the right lead alloy to the right sticky ink mixture, towards the simple construct of the printed book. This project too [Xanadu] has taken a lot of work for a similarly simple literary construct. I've never thought of this as technology, but rather, as what electronic literature ought to be.

Most of what people call technology is constructs. Artificial, imaginary constructs that people made up. "Directory," "desktop," "game," "spreadsheet" — all imagined constructs that people have dreamed up and implemented in the computer. Today I offer one more construct for your consideration. [...]

Movable type took a lot of technical decisions, like matching the right lead alloy to the right sticky ink mixture, towards the simple construct of the printed book. This project too [Xanadu] has taken a lot of work for a similarly simple literary construct. I've never thought of this as technology, but rather, as what electronic literature ought to be.

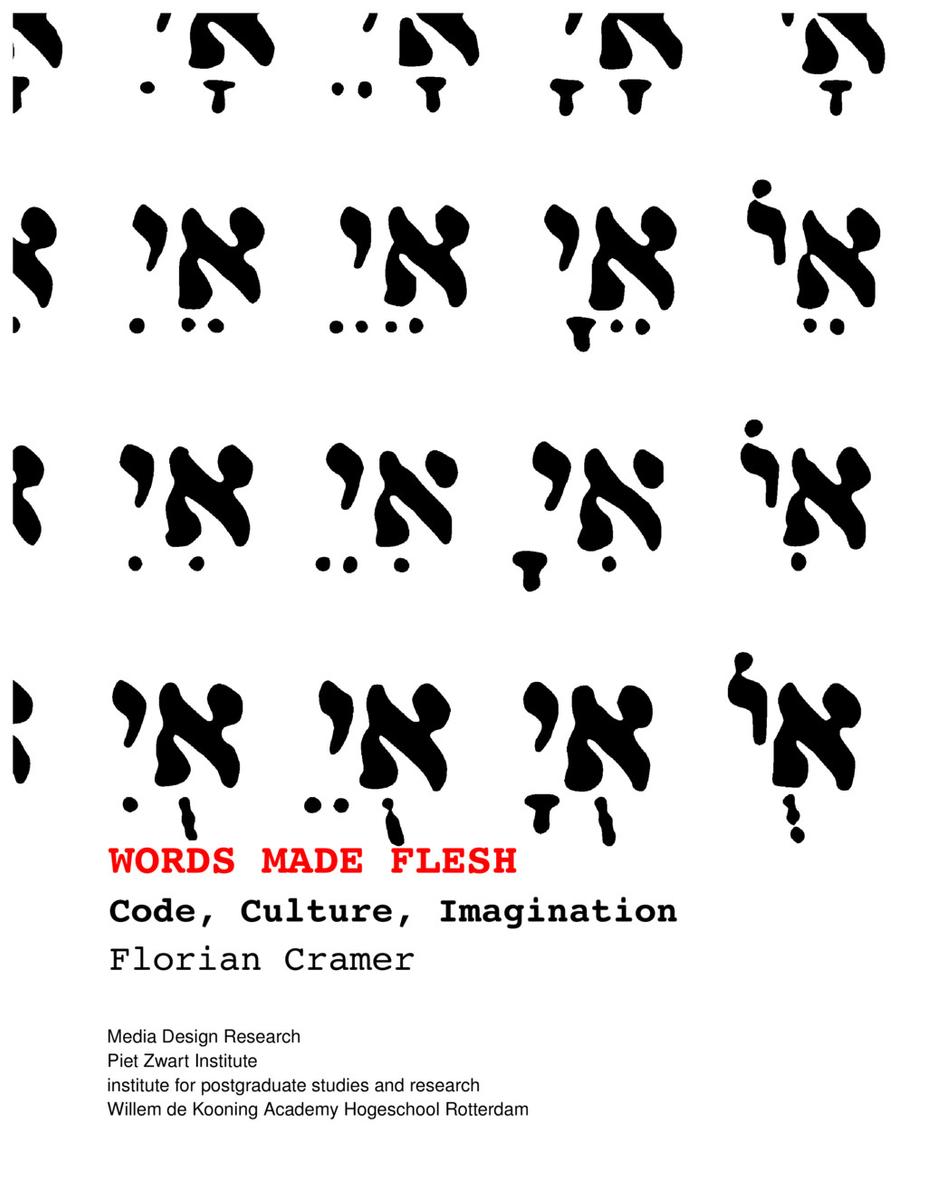

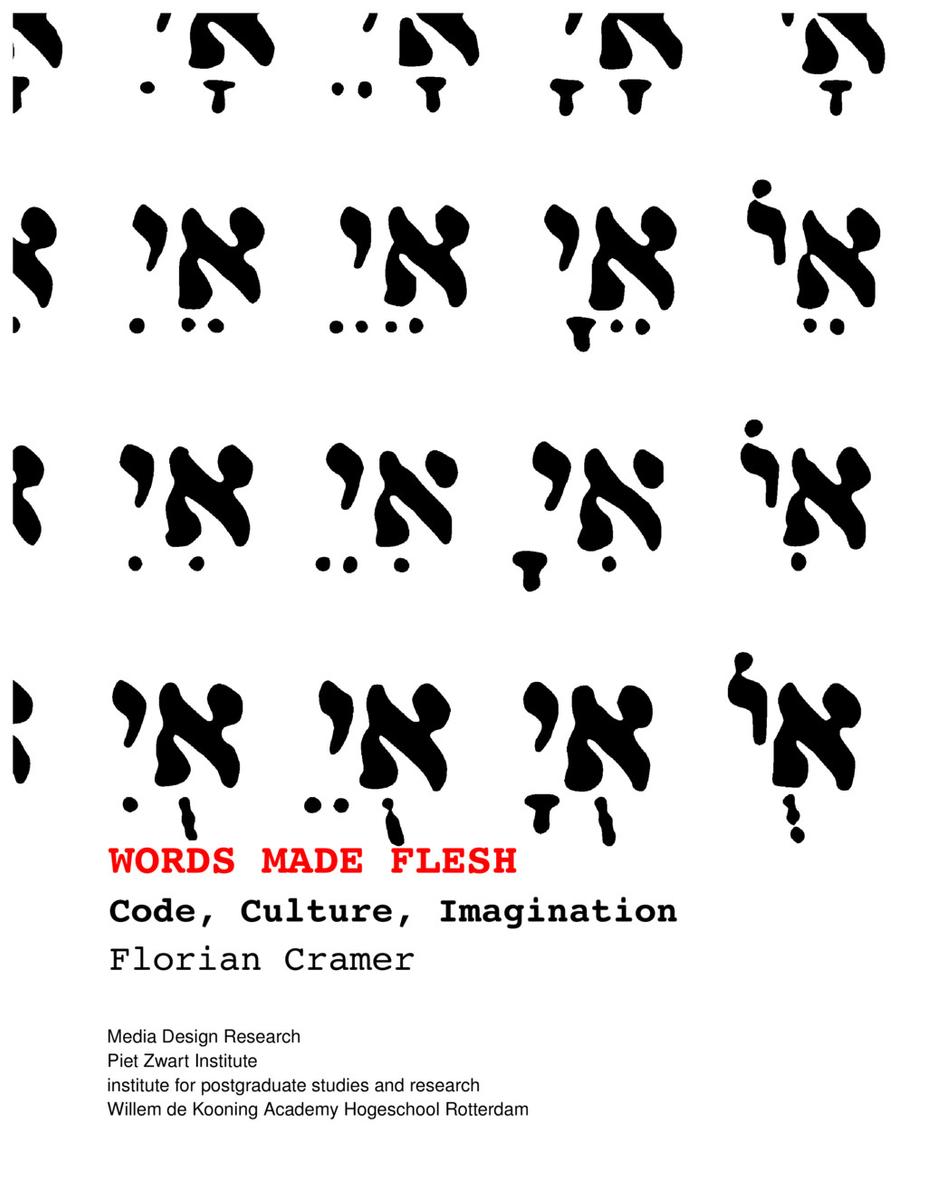

All rewritings, whatever their intention, reflect a certain ideology and a poetics … the study of the manipulation processes of literature as exemplified by translation can help us towards a greater awareness of the world in which we live.

All rewritings, whatever their intention, reflect a certain ideology and a poetics … the study of the manipulation processes of literature as exemplified by translation can help us towards a greater awareness of the world in which we live.

All rewritings, whatever their intention, reflect a certain ideology and a poetics … the study of the manipulation processes of literature as exemplified by translation can help us towards a greater awareness of the world in which we live.

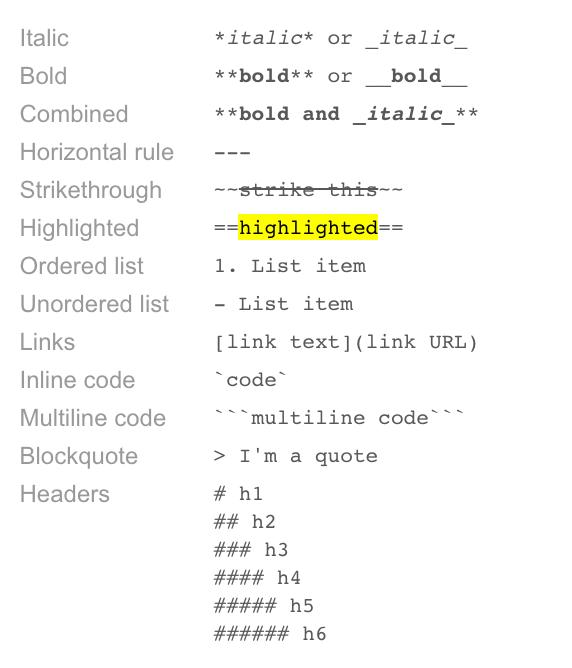

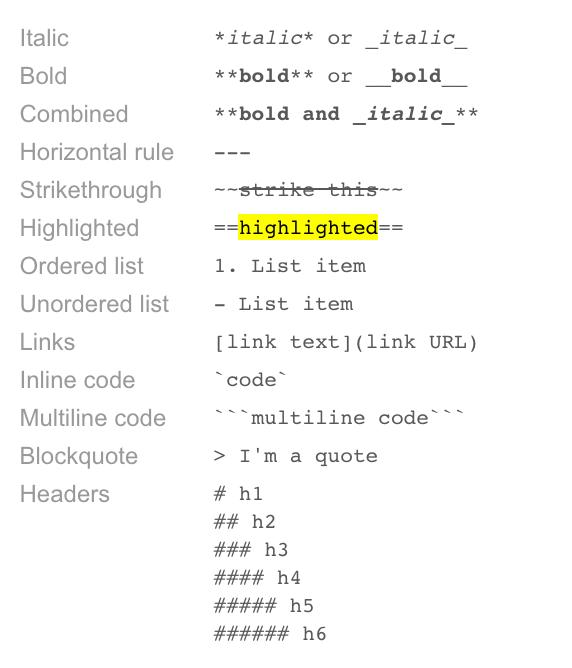

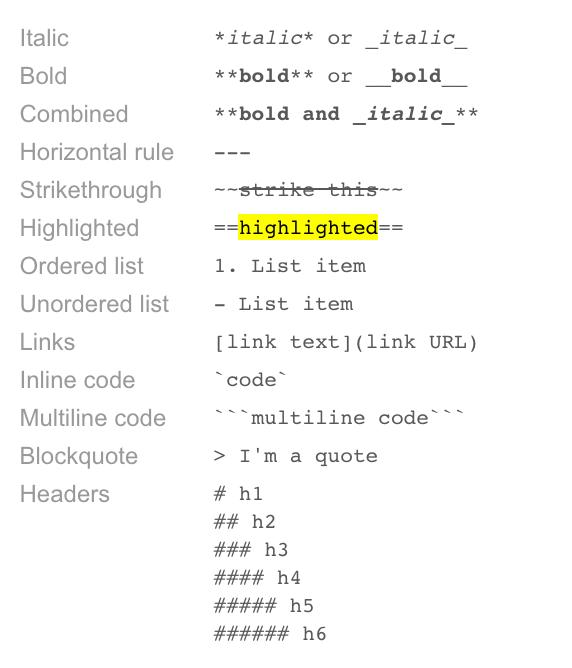

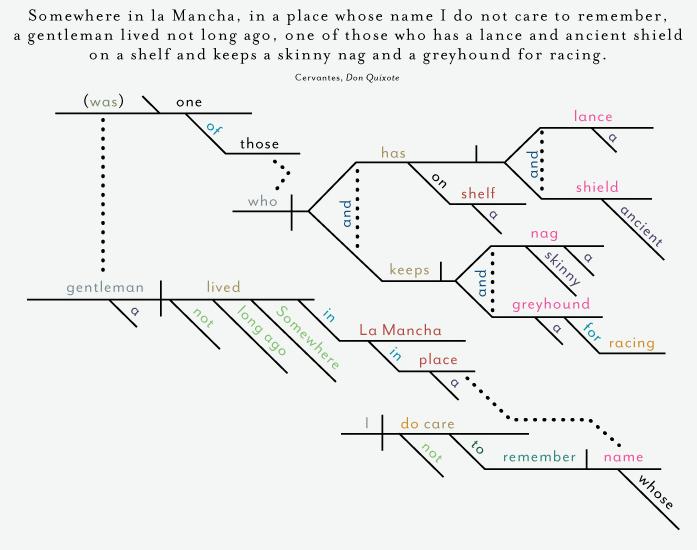

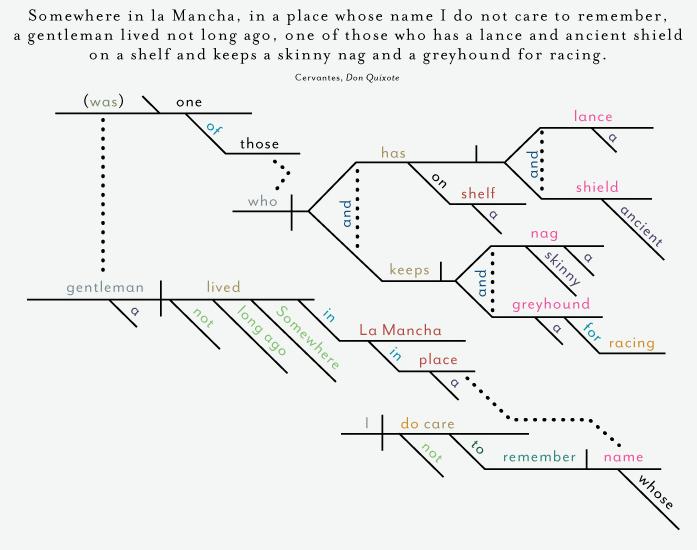

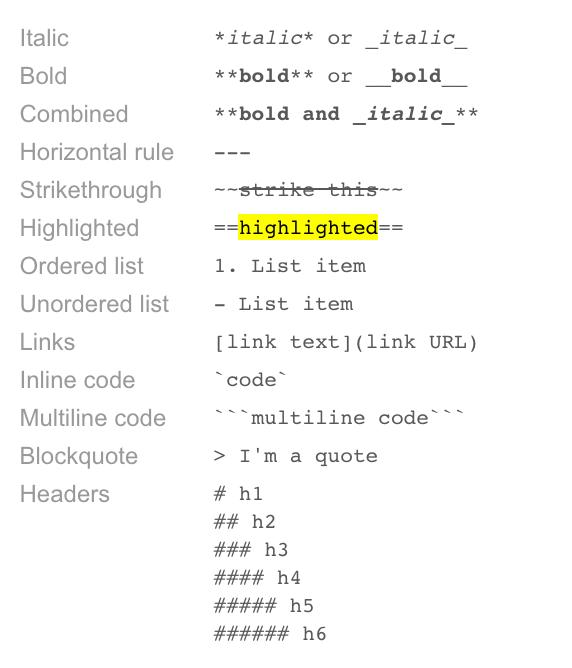

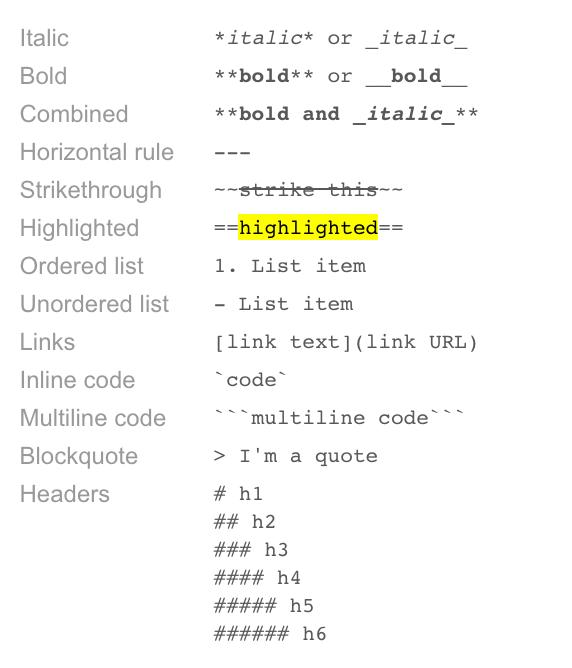

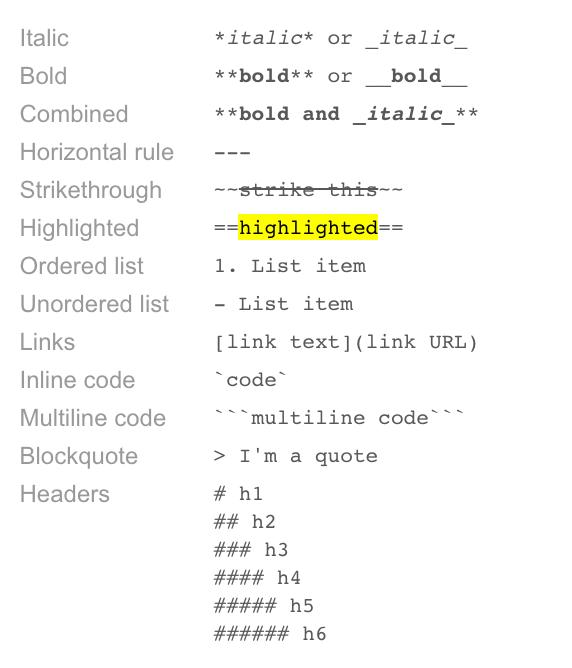

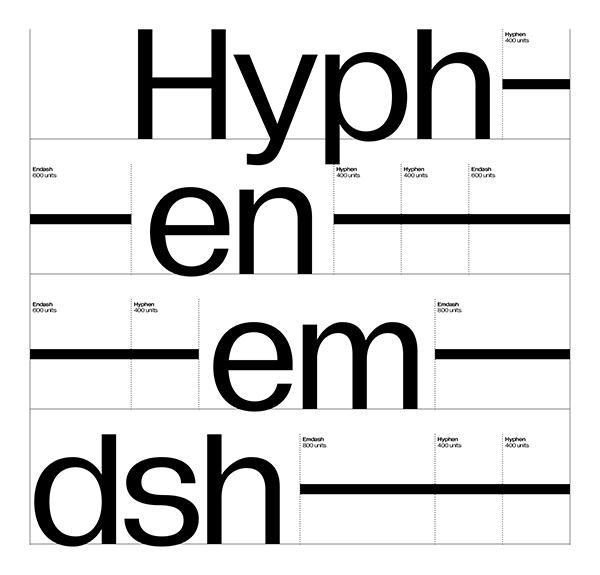

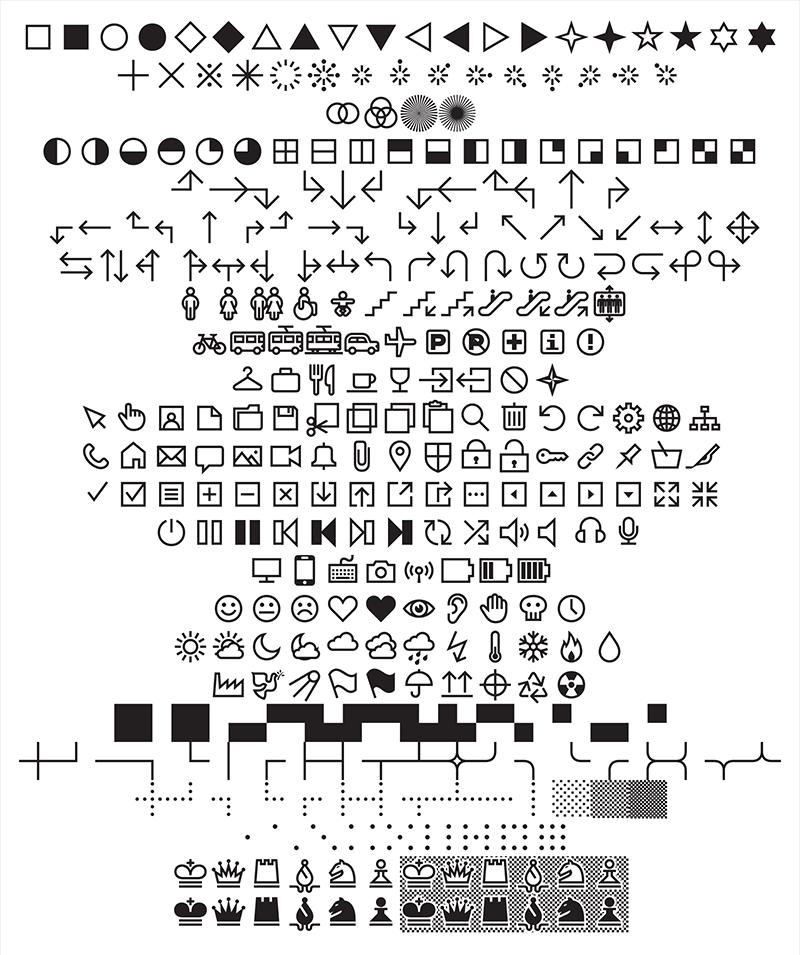

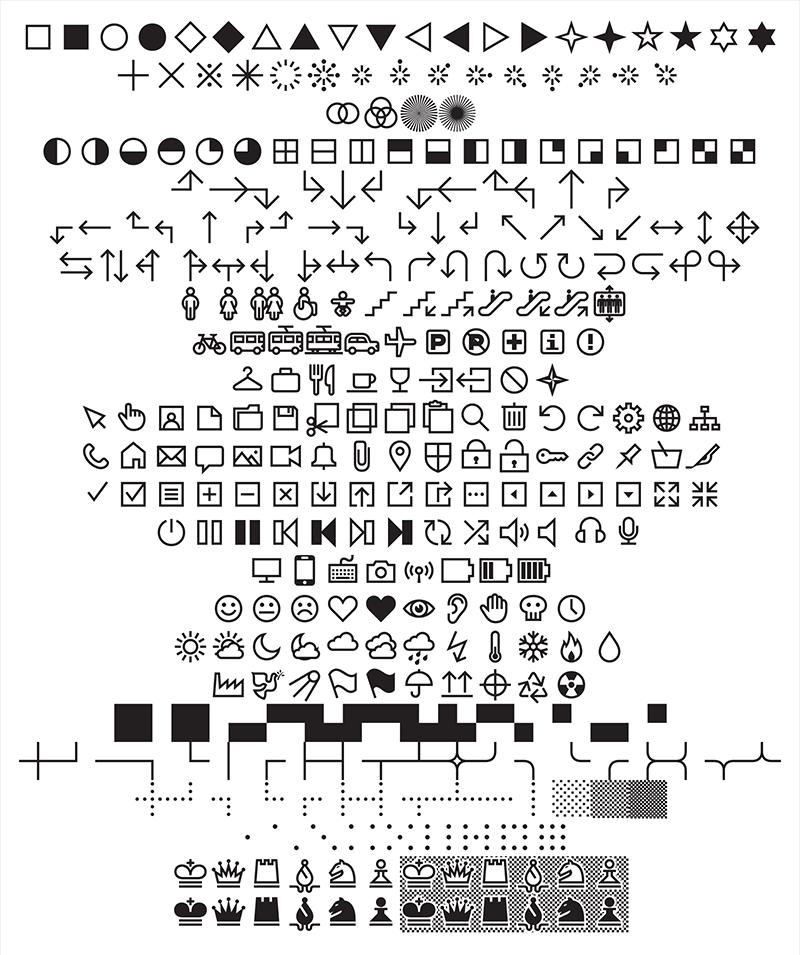

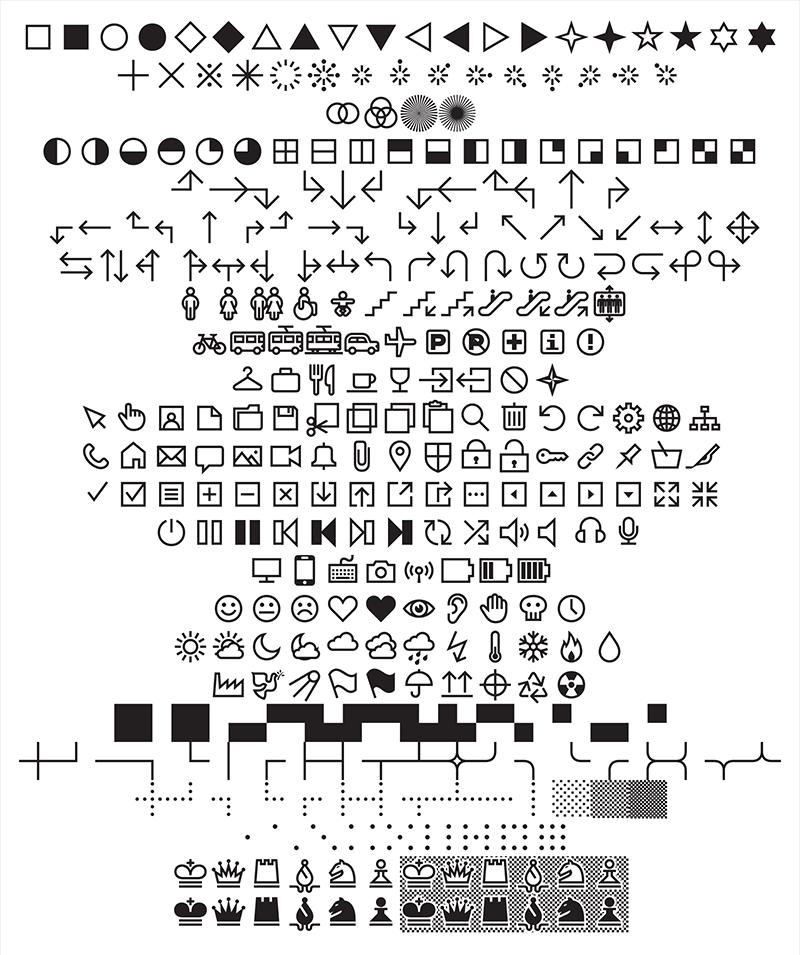

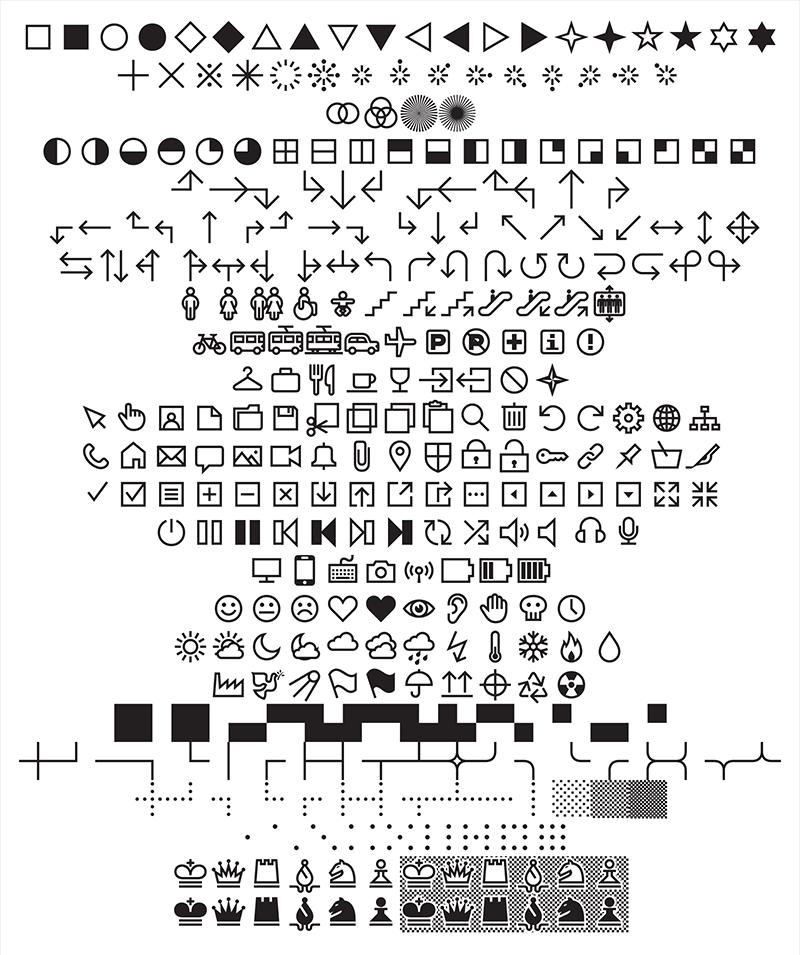

syn·tax /ˈsinˌtaks/ noun

the arrangement of words and phrases to create well-formed sentences in a language. - a set of rules for or an analysis of the syntax of a language. plural noun: syntaxes "generative syntax"

Origin: late 16th century: from French syntaxe, or via late Latin from Greek suntaxis, from sun- ‘together’ + tassein ‘arrange’.

syn·tax /ˈsinˌtaks/ noun

the arrangement of words and phrases to create well-formed sentences in a language. - a set of rules for or an analysis of the syntax of a language. plural noun: syntaxes "generative syntax"

Origin: late 16th century: from French syntaxe, or via late Latin from Greek suntaxis, from sun- ‘together’ + tassein ‘arrange’.

syn·tax /ˈsinˌtaks/ noun

the arrangement of words and phrases to create well-formed sentences in a language. - a set of rules for or an analysis of the syntax of a language. plural noun: syntaxes "generative syntax"

Origin: late 16th century: from French syntaxe, or via late Latin from Greek suntaxis, from sun- ‘together’ + tassein ‘arrange’.

We don’t walk down the street saying to ourselves: ‘As I walk down the street, comma, I contemplate the question of faith, or adultery, or x or y or z.’

We don’t walk down the street saying to ourselves: ‘As I walk down the street, comma, I contemplate the question of faith, or adultery, or x or y or z.’

We don’t walk down the street saying to ourselves: ‘As I walk down the street, comma, I contemplate the question of faith, or adultery, or x or y or z.’

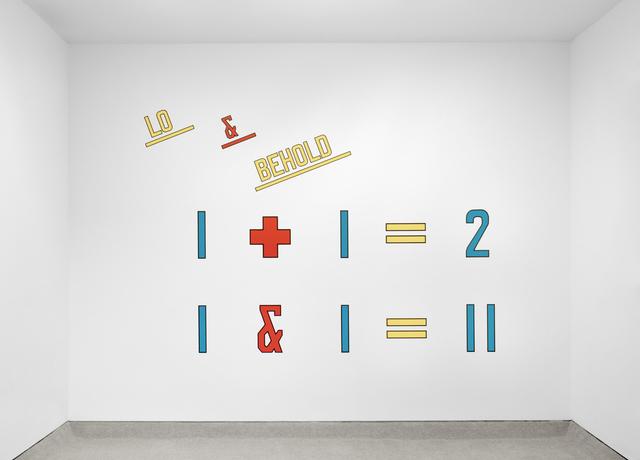

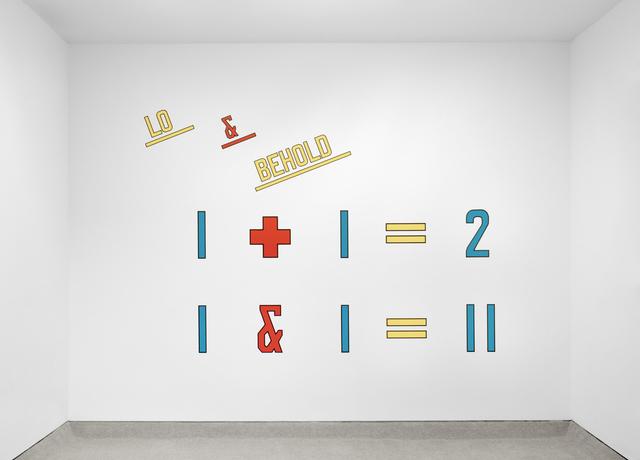

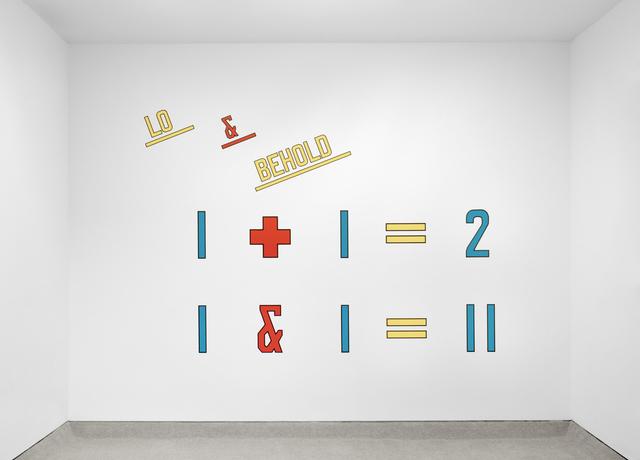

[...] I must have been five years old and I was trailing my hand in the water and I thought about how the water was moving around my fingers — opening on one side and closing on the other — and that changing system of relationships where everything was kind of similar, kind of the same, and yet different. That was so difficult to visualize and express. And just generalizing that the world is a system of ever-changing relationships and structures struck me as a vast truth. Which it is! [...]

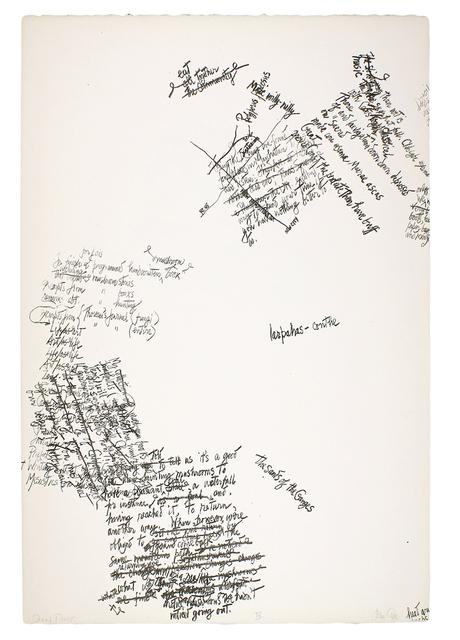

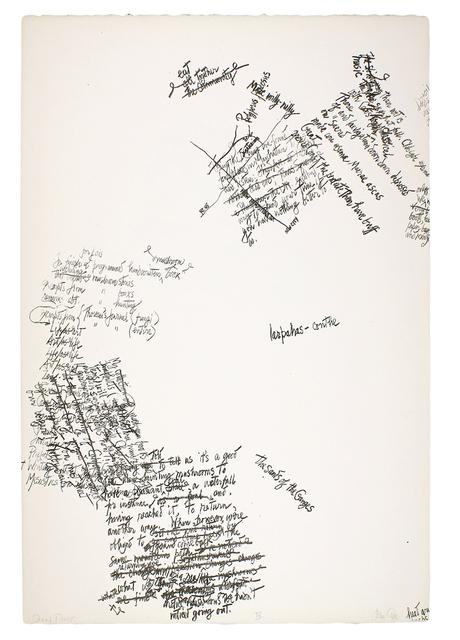

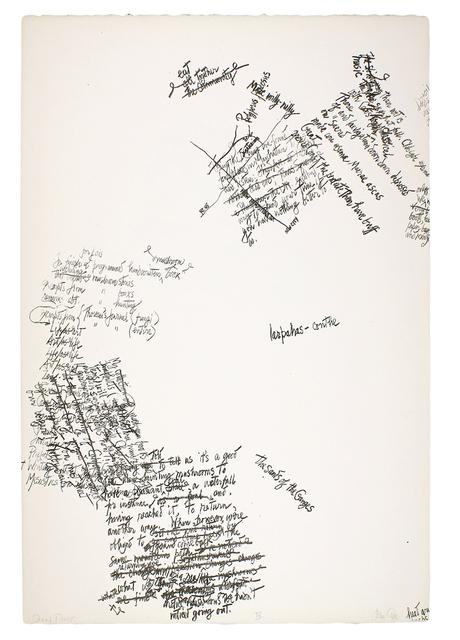

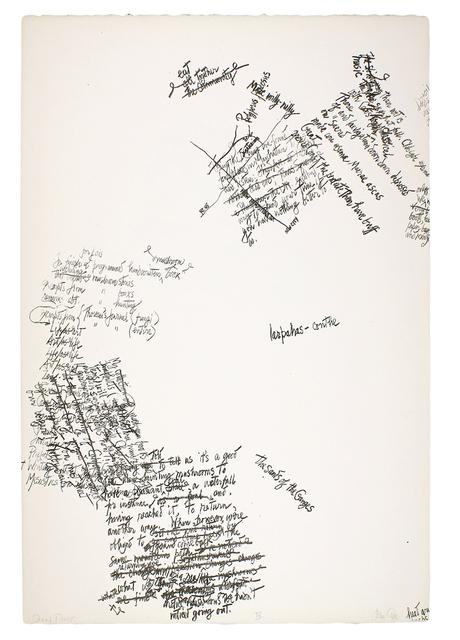

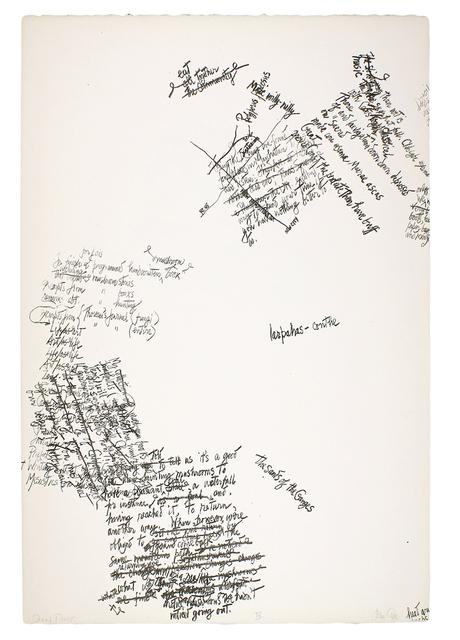

Writing is the process of reducing a tapestry of interconnection to a narrow sequence. This is a wrongful compression of what should spread out.

In today's computers they betrayed that because there's no system for decent "cut-and-paste" and they changed the meaning of the words "cut-and-paste" and pretended it was the same thing. [...] I consider that to be a crime against humanity [...] because humanity has no decent writing tools. In any case, this is the problem of interconnection and representation and sequentialization all similar to the issue of water.

[...] I must have been five years old and I was trailing my hand in the water and I thought about how the water was moving around my fingers — opening on one side and closing on the other — and that changing system of relationships where everything was kind of similar, kind of the same, and yet different. That was so difficult to visualize and express. And just generalizing that the world is a system of ever-changing relationships and structures struck me as a vast truth. Which it is! [...]

Writing is the process of reducing a tapestry of interconnection to a narrow sequence. This is a wrongful compression of what should spread out.

In today's computers they betrayed that because there's no system for decent "cut-and-paste" and they changed the meaning of the words "cut-and-paste" and pretended it was the same thing. [...] I consider that to be a crime against humanity [...] because humanity has no decent writing tools. In any case, this is the problem of interconnection and representation and sequentialization all similar to the issue of water.

[...] I must have been five years old and I was trailing my hand in the water and I thought about how the water was moving around my fingers — opening on one side and closing on the other — and that changing system of relationships where everything was kind of similar, kind of the same, and yet different. That was so difficult to visualize and express. And just generalizing that the world is a system of ever-changing relationships and structures struck me as a vast truth. Which it is! [...]

Writing is the process of reducing a tapestry of interconnection to a narrow sequence. This is a wrongful compression of what should spread out.

In today's computers they betrayed that because there's no system for decent "cut-and-paste" and they changed the meaning of the words "cut-and-paste" and pretended it was the same thing. [...] I consider that to be a crime against humanity [...] because humanity has no decent writing tools. In any case, this is the problem of interconnection and representation and sequentialization all similar to the issue of water.

Concepts are concrete assemblages, like the configurations of a machine, but the plane [of immanence] is the abstract machine of which these assemblages are the working parts.

Concepts are concrete assemblages, like the configurations of a machine, but the plane [of immanence] is the abstract machine of which these assemblages are the working parts.

Concepts are concrete assemblages, like the configurations of a machine, but the plane [of immanence] is the abstract machine of which these assemblages are the working parts.

syn·tax /ˈsinˌtaks/ noun

the arrangement of words and phrases to create well-formed sentences in a language. - a set of rules for or an analysis of the syntax of a language. plural noun: syntaxes "generative syntax"

Origin: late 16th century: from French syntaxe, or via late Latin from Greek suntaxis, from sun- ‘together’ + tassein ‘arrange’.

syn·tax /ˈsinˌtaks/ noun

the arrangement of words and phrases to create well-formed sentences in a language. - a set of rules for or an analysis of the syntax of a language. plural noun: syntaxes "generative syntax"

Origin: late 16th century: from French syntaxe, or via late Latin from Greek suntaxis, from sun- ‘together’ + tassein ‘arrange’.

syn·tax /ˈsinˌtaks/ noun

the arrangement of words and phrases to create well-formed sentences in a language. - a set of rules for or an analysis of the syntax of a language. plural noun: syntaxes "generative syntax"

Origin: late 16th century: from French syntaxe, or via late Latin from Greek suntaxis, from sun- ‘together’ + tassein ‘arrange’.

[...] I must have been five years old and I was trailing my hand in the water and I thought about how the water was moving around my fingers — opening on one side and closing on the other — and that changing system of relationships where everything was kind of similar, kind of the same, and yet different. That was so difficult to visualize and express. And just generalizing that the world is a system of ever-changing relationships and structures struck me as a vast truth. Which it is! [...]

Writing is the process of reducing a tapestry of interconnection to a narrow sequence. This is a wrongful compression of what should spread out.

In today's computers they betrayed that because there's no system for decent "cut-and-paste" and they changed the meaning of the words "cut-and-paste" and pretended it was the same thing. [...] I consider that to be a crime against humanity [...] because humanity has no decent writing tools. In any case, this is the problem of interconnection and representation and sequentialization all similar to the issue of water.

[...] I must have been five years old and I was trailing my hand in the water and I thought about how the water was moving around my fingers — opening on one side and closing on the other — and that changing system of relationships where everything was kind of similar, kind of the same, and yet different. That was so difficult to visualize and express. And just generalizing that the world is a system of ever-changing relationships and structures struck me as a vast truth. Which it is! [...]

Writing is the process of reducing a tapestry of interconnection to a narrow sequence. This is a wrongful compression of what should spread out.

In today's computers they betrayed that because there's no system for decent "cut-and-paste" and they changed the meaning of the words "cut-and-paste" and pretended it was the same thing. [...] I consider that to be a crime against humanity [...] because humanity has no decent writing tools. In any case, this is the problem of interconnection and representation and sequentialization all similar to the issue of water.

[...] I must have been five years old and I was trailing my hand in the water and I thought about how the water was moving around my fingers — opening on one side and closing on the other — and that changing system of relationships where everything was kind of similar, kind of the same, and yet different. That was so difficult to visualize and express. And just generalizing that the world is a system of ever-changing relationships and structures struck me as a vast truth. Which it is! [...]

Writing is the process of reducing a tapestry of interconnection to a narrow sequence. This is a wrongful compression of what should spread out.

In today's computers they betrayed that because there's no system for decent "cut-and-paste" and they changed the meaning of the words "cut-and-paste" and pretended it was the same thing. [...] I consider that to be a crime against humanity [...] because humanity has no decent writing tools. In any case, this is the problem of interconnection and representation and sequentialization all similar to the issue of water.

We don’t walk down the street saying to ourselves: ‘As I walk down the street, comma, I contemplate the question of faith, or adultery, or x or y or z.’

We don’t walk down the street saying to ourselves: ‘As I walk down the street, comma, I contemplate the question of faith, or adultery, or x or y or z.’

We don’t walk down the street saying to ourselves: ‘As I walk down the street, comma, I contemplate the question of faith, or adultery, or x or y or z.’

All rewritings, whatever their intention, reflect a certain ideology and a poetics … the study of the manipulation processes of literature as exemplified by translation can help us towards a greater awareness of the world in which we live.

All rewritings, whatever their intention, reflect a certain ideology and a poetics … the study of the manipulation processes of literature as exemplified by translation can help us towards a greater awareness of the world in which we live.

All rewritings, whatever their intention, reflect a certain ideology and a poetics … the study of the manipulation processes of literature as exemplified by translation can help us towards a greater awareness of the world in which we live.

Alfred Korzybski remarked that "the map is not the territory" and that "the word is not the thing", encapsulating his view that an abstraction derived from something, or a reaction to it, is not the thing itself.

Alfred Korzybski remarked that "the map is not the territory" and that "the word is not the thing", encapsulating his view that an abstraction derived from something, or a reaction to it, is not the thing itself.

Alfred Korzybski remarked that "the map is not the territory" and that "the word is not the thing", encapsulating his view that an abstraction derived from something, or a reaction to it, is not the thing itself.

Exclamation points survive as tokens of the disjunction between idea and realization in that period, and their impotent evocation redeems them in memory: a desperate written gesture that yearns in vain to transcend language.

Exclamation points survive as tokens of the disjunction between idea and realization in that period, and their impotent evocation redeems them in memory: a desperate written gesture that yearns in vain to transcend language.

Exclamation points survive as tokens of the disjunction between idea and realization in that period, and their impotent evocation redeems them in memory: a desperate written gesture that yearns in vain to transcend language.

Imagine a sentence. “I went looking for adventure.”

Imagine another one. “I never returned.”

Now imagine a sentence gradient between them—not a story, but a smooth interpolation of meaning. This is a weird thing to ask for! I’d never even bothered to imagine an interpolation between sentences before encountering the idea in a recent academic paper. But as soon as I did, I found it captivating, both for the thing itself—a sentence… gradient?—and for the larger artifact it suggested: a dense cloud of sentences, all related; a space you might navigate and explore.

Imagine a sentence. “I went looking for adventure.”

Imagine another one. “I never returned.”

Now imagine a sentence gradient between them—not a story, but a smooth interpolation of meaning. This is a weird thing to ask for! I’d never even bothered to imagine an interpolation between sentences before encountering the idea in a recent academic paper. But as soon as I did, I found it captivating, both for the thing itself—a sentence… gradient?—and for the larger artifact it suggested: a dense cloud of sentences, all related; a space you might navigate and explore.

Imagine a sentence. “I went looking for adventure.”

Imagine another one. “I never returned.”

Now imagine a sentence gradient between them—not a story, but a smooth interpolation of meaning. This is a weird thing to ask for! I’d never even bothered to imagine an interpolation between sentences before encountering the idea in a recent academic paper. But as soon as I did, I found it captivating, both for the thing itself—a sentence… gradient?—and for the larger artifact it suggested: a dense cloud of sentences, all related; a space you might navigate and explore.

Concepts are concrete assemblages, like the configurations of a machine, but the plane [of immanence] is the abstract machine of which these assemblages are the working parts.

Concepts are concrete assemblages, like the configurations of a machine, but the plane [of immanence] is the abstract machine of which these assemblages are the working parts.

Concepts are concrete assemblages, like the configurations of a machine, but the plane [of immanence] is the abstract machine of which these assemblages are the working parts.

Exclamation points survive as tokens of the disjunction between idea and realization in that period, and their impotent evocation redeems them in memory: a desperate written gesture that yearns in vain to transcend language.

Exclamation points survive as tokens of the disjunction between idea and realization in that period, and their impotent evocation redeems them in memory: a desperate written gesture that yearns in vain to transcend language.

Exclamation points survive as tokens of the disjunction between idea and realization in that period, and their impotent evocation redeems them in memory: a desperate written gesture that yearns in vain to transcend language.