syn·site

in Robert Smithson's terms*: (a partially generated and generative theory) The Synsite (an entangled situating) is an inter-dimensional picture that is amorphous, and yet it represents an interweaving of actual and virtual sites (an amalgamation of the Pine Barrens Plains, ML-scene processing, and the hyper-saturated yellow-green of a pool of disintegrated oak pollen, for instance). It is by this inter-dimensional metaphor that one entangled situating can represent another entangled situating, which does not resemble it—thus The Synsite. To comprehend this language of situating is to appreciate the metaphor between the syntactical construct and the complex of ideas, permitting the former to operate as a inter-dimensional picture that doesn't look like a picture. ... Between the actual-virtual sites in their respective planes and The Synsite itself exists a metaphoric space of collapsible significance. Perhaps "travel" through this space is a boundless metaphor. Everything in and between the entangled situatings could transform into physical metaphorical material devoid of natural meanings or realistic assumptions. Let us say that one embarks on many fictitious journeys at once if one decides to seek the site of the Synsite. Each “journey” is invented, devised, artificial; one might call it a syn-trip to a site from a Synsite. Once one arrives at the “assembly,” one discovers that it is man-made in the form of a network, and that she mapped this network in an aesthetic and temporal entanglement rather than specific political or economic boundaries.

This revisited theory is currently collaborative but could be surrendered to the faceless corpus of AGI at any time. Like the sources they scrape, theories are also both used and abandoned. That theories are constant is dubious; that sources are singularly credited is increasingly doubtful. Vanished theories compose the dense data layers of countless LLMs.

in Robert Smithson's terms*: (a partially generated and generative theory) The Synsite (an entangled situating) is an inter-dimensional picture that is amorphous, and yet it represents an interweaving of actual and virtual sites (an amalgamation of the Pine Barrens Plains, ML-scene processing, and the hyper-saturated yellow-green of a pool of disintegrated oak pollen, for instance). It is by this inter-dimensional metaphor that one entangled situating can represent another entangled situating, which does not resemble it—thus The Synsite. To comprehend this language of situating is to appreciate the metaphor between the syntactical construct and the complex of ideas, permitting the former to operate as a inter-dimensional picture that doesn't look like a picture. ... Between the actual-virtual sites in their respective planes and The Synsite itself exists a metaphoric space of collapsible significance. Perhaps "travel" through this space is a boundless metaphor. Everything in and between the entangled situatings could transform into physical metaphorical material devoid of natural meanings or realistic assumptions. Let us say that one embarks on many fictitious journeys at once if one decides to seek the site of the Synsite. Each “journey” is invented, devised, artificial; one might call it a syn-trip to a site from a Synsite. Once one arrives at the “assembly,” one discovers that it is man-made in the form of a network, and that she mapped this network in an aesthetic and temporal entanglement rather than specific political or economic boundaries.

This revisited theory is currently collaborative but could be surrendered to the faceless corpus of AGI at any time. Like the sources they scrape, theories are also both used and abandoned. That theories are constant is dubious; that sources are singularly credited is increasingly doubtful. Vanished theories compose the dense data layers of countless LLMs.

SYN (along with, at the same time | from Greek SYN, with | ~SYNTHETIC) + SITE (N: point of event, occupied space, internet address; V: to place in position | from Latin SITUS, location, idleness, forgetfulness | ~WEBSITE ¬cite ¬sight), cf. SITE/NON-SITE (from Robert Smithson, A PROVISIONAL THEORY OF NONSITES, 1968)

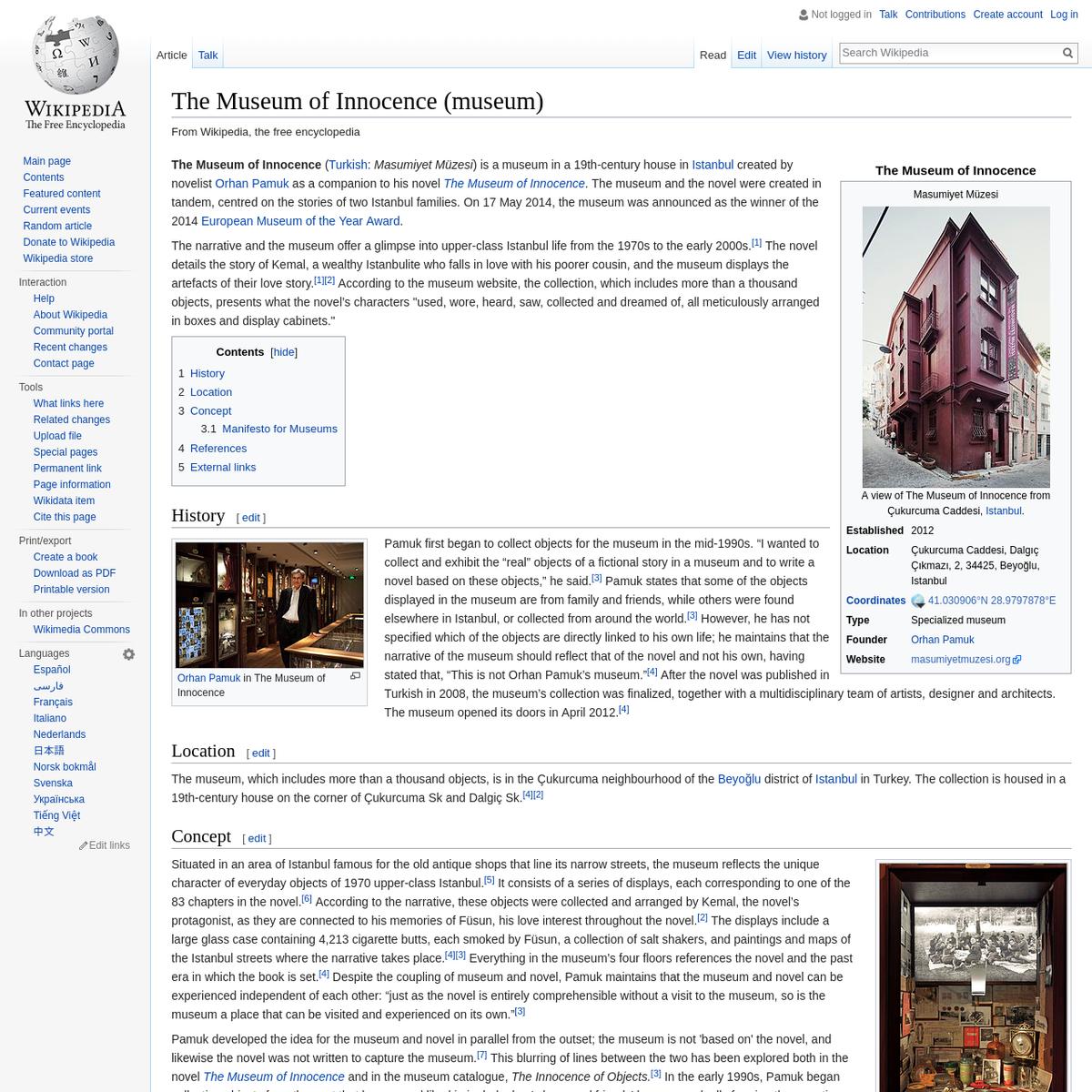

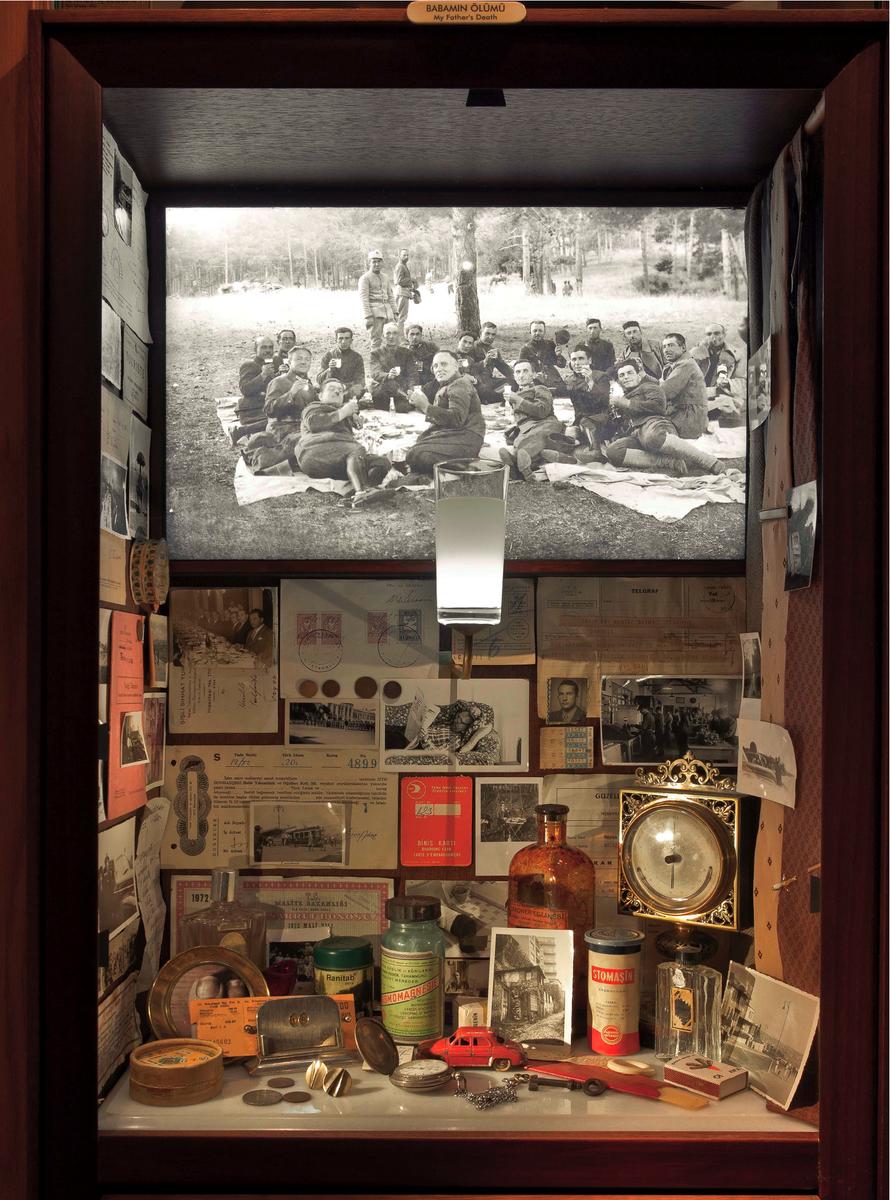

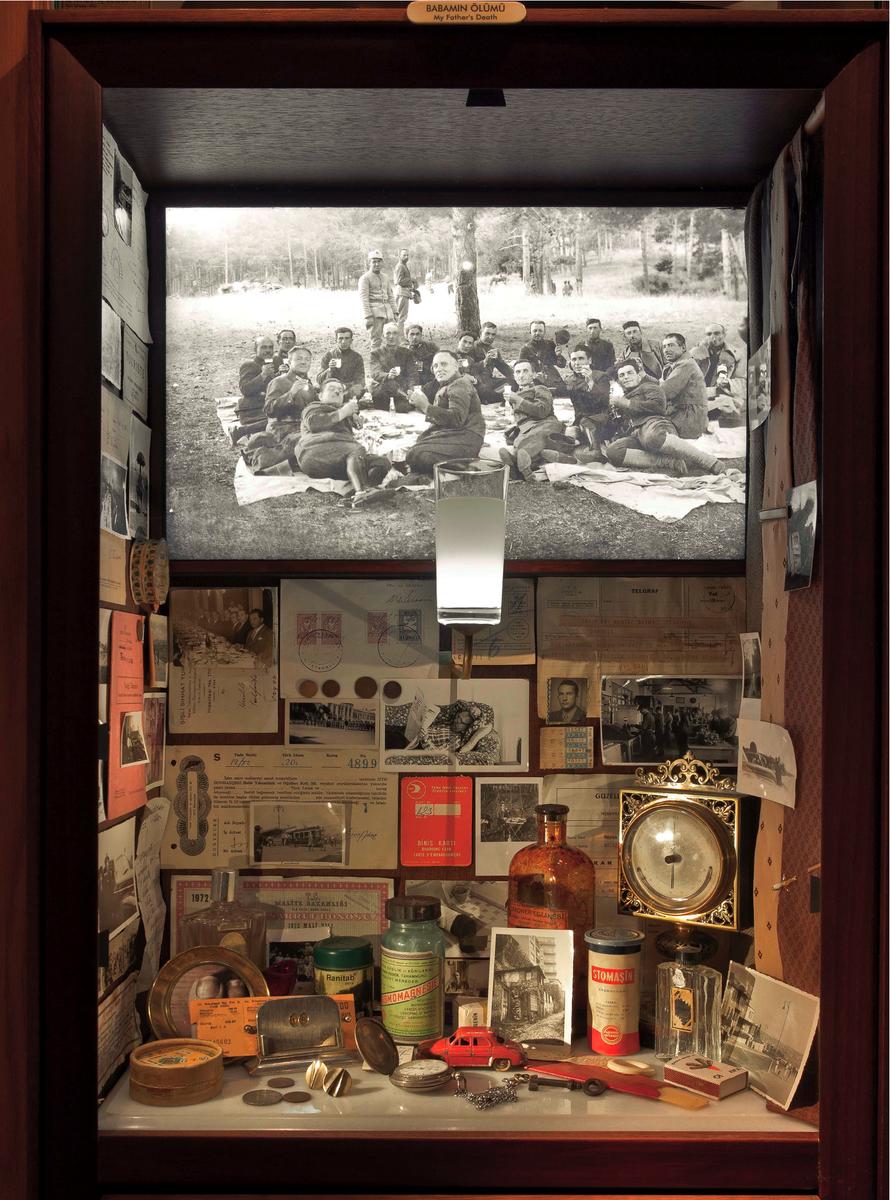

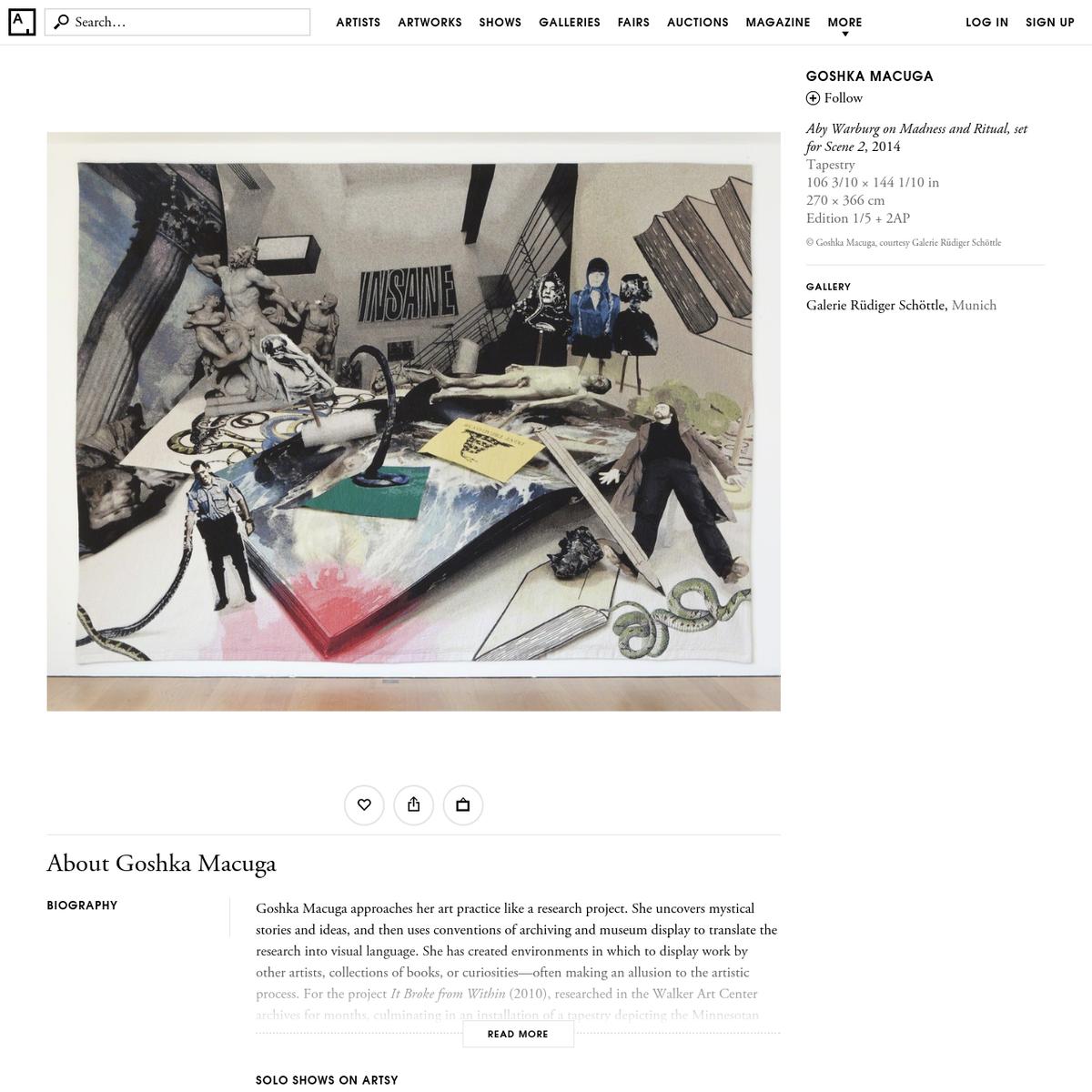

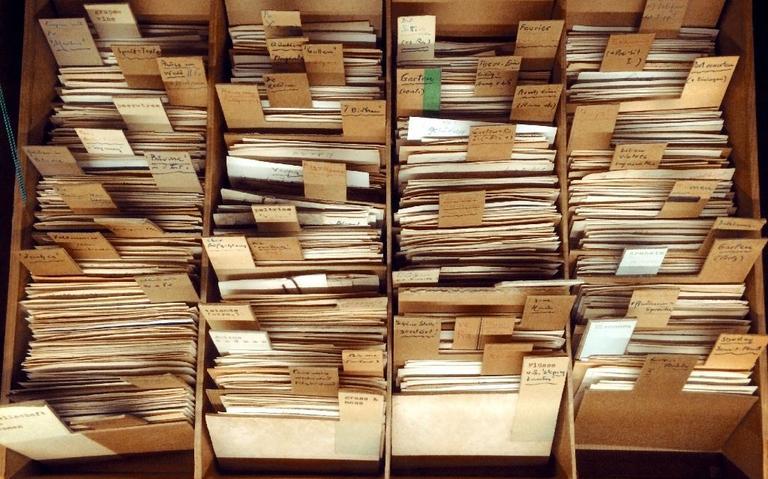

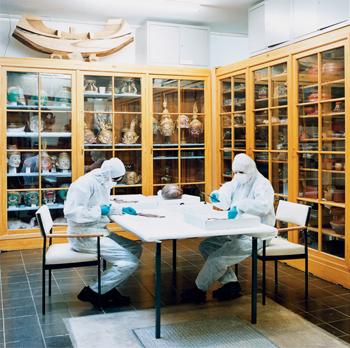

I love museums and I am not alone in finding that they make me happier with each passing day. I take museums very seriously, and that sometimes leads to angry, forceful thoughts. But I do not have it in me to speak about museums with anger. In my childhood there were very few museums in Istanbul. Most of these were historical monuments or, quite rare outside the Western world, they were places with an air of a government office about them. Later, the small museums in the backstreets of European cities led me to realize that museums – just like novels – can also speak for individuals. That is not to understate the importance of the Louvre, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Topkapi Palace, the British Museum, the Prado, the Vatican Museums – all veritable treasures of humankind. But I am against these precious monumental institutions being used as blueprints for future museums. Museums should explore and uncover the universe and humanity of the new and modern man emerging from increasingly wealthy non-Western nations. The aim of big, state-sponsored museums, on the other hand, is to represent the state. This is neither a good nor innocent objective.

I would like to outline my thoughts in order:

1/ Large national museums such as the Louvre and the Hermitage took shape and turned into essential tourist destinations alongside the opening of royal and imperial palaces to the public. These institutions, now national symbols, present the story of the nation – history, in a word – as being far more important than the stories of individuals. This is unfortunate, because the stories of individuals are much better suited to displaying the depths of our humanity.

2/ We can see that the transitions from palaces to national museums and from epics to novels are parallel processes. Epics are like palaces and speak of the heroic exploits of the old kings who lived in them. National museums, then, should be like novels; but they are not.

3/ We don’t need more museums that try to construct the historical narratives of a society, community, team, nation, state, tribe, company, or species. We all know that the ordinary, everyday stories of individuals are richer, more humane, and much more joyful.

4/ Demonstrating the wealth of Chinese, Indian, Mexican, Iranian, or Turkish history and culture is not an issue – it must be done, of course, but it is not difficult to do. The real challenge is to use museums to tell, with the same brilliance, depth, and power, the stories of the individual human beings living in these countries.

5/ The measure of a museum’s success should not be its ability to represent a state, a nation or company, or a particular history. It should be its capacity to reveal the humanity of individuals.

6/ It is imperative that museums become smaller, more individualistic, and cheaper. This is the only way that they will ever tell stories on a human scale. Big museums with their wide doors call upon us to forget our humanity and embrace the state and its human masses. This is why millions outside the Western world are afraid of going to museums.

7/ The aim of present and future museums must not be to represent the state, but to re-create the world of single human beings – the same human beings who have labored under ruthless oppression for hundreds of years.

8/ The resources that are channeled into monumental, symbolic museums should be diverted into smaller museums that tell the stories of individuals. These resources should also be used to encourage and support people in turning their own small homes and stories into “exhibition” spaces.

9/ If objects are not uprooted from their environs and their streets, but are situated with care and ingenuity in their natural homes, they will already portray their own stories.

10/ Monumental buildings that dominate neighborhoods and entire cities do not bring out our humanity; on the contrary, they quash it. Instead, we need modest museums that honor the neighborhoods and streets and the homes and shops nearby, and turn them into elements of their exhibitions.

11/ The future of museums is inside our own homes.

The picture, in fact, is very simple:

WE HAD:

- Epics

- Representation

- Monuments

- Histories

- Nations

- Groups and teams

- Large and expensive

WE NEED

- Novels

- Expression

- Homes

- Stories

- Persons

- Individuals

- Small and cheap

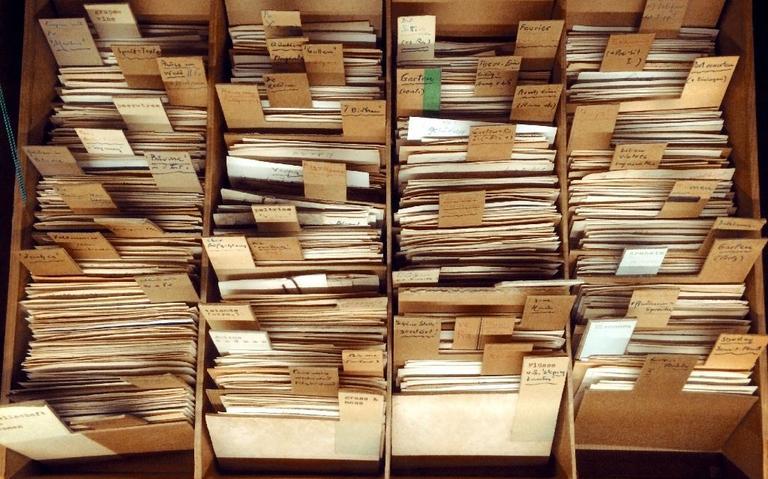

I love museums and I am not alone in finding that they make me happier with each passing day. I take museums very seriously, and that sometimes leads to angry, forceful thoughts. But I do not have it in me to speak about museums with anger. In my childhood there were very few museums in Istanbul. Most of these were historical monuments or, quite rare outside the Western world, they were places with an air of a government office about them. Later, the small museums in the backstreets of European cities led me to realize that museums – just like novels – can also speak for individuals. That is not to understate the importance of the Louvre, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Topkapi Palace, the British Museum, the Prado, the Vatican Museums – all veritable treasures of humankind. But I am against these precious monumental institutions being used as blueprints for future museums. Museums should explore and uncover the universe and humanity of the new and modern man emerging from increasingly wealthy non-Western nations. The aim of big, state-sponsored museums, on the other hand, is to represent the state. This is neither a good nor innocent objective.

I would like to outline my thoughts in order:

1/ Large national museums such as the Louvre and the Hermitage took shape and turned into essential tourist destinations alongside the opening of royal and imperial palaces to the public. These institutions, now national symbols, present the story of the nation – history, in a word – as being far more important than the stories of individuals. This is unfortunate, because the stories of individuals are much better suited to displaying the depths of our humanity.

2/ We can see that the transitions from palaces to national museums and from epics to novels are parallel processes. Epics are like palaces and speak of the heroic exploits of the old kings who lived in them. National museums, then, should be like novels; but they are not.

3/ We don’t need more museums that try to construct the historical narratives of a society, community, team, nation, state, tribe, company, or species. We all know that the ordinary, everyday stories of individuals are richer, more humane, and much more joyful.

4/ Demonstrating the wealth of Chinese, Indian, Mexican, Iranian, or Turkish history and culture is not an issue – it must be done, of course, but it is not difficult to do. The real challenge is to use museums to tell, with the same brilliance, depth, and power, the stories of the individual human beings living in these countries.

5/ The measure of a museum’s success should not be its ability to represent a state, a nation or company, or a particular history. It should be its capacity to reveal the humanity of individuals.

6/ It is imperative that museums become smaller, more individualistic, and cheaper. This is the only way that they will ever tell stories on a human scale. Big museums with their wide doors call upon us to forget our humanity and embrace the state and its human masses. This is why millions outside the Western world are afraid of going to museums.

7/ The aim of present and future museums must not be to represent the state, but to re-create the world of single human beings – the same human beings who have labored under ruthless oppression for hundreds of years.

8/ The resources that are channeled into monumental, symbolic museums should be diverted into smaller museums that tell the stories of individuals. These resources should also be used to encourage and support people in turning their own small homes and stories into “exhibition” spaces.

9/ If objects are not uprooted from their environs and their streets, but are situated with care and ingenuity in their natural homes, they will already portray their own stories.

10/ Monumental buildings that dominate neighborhoods and entire cities do not bring out our humanity; on the contrary, they quash it. Instead, we need modest museums that honor the neighborhoods and streets and the homes and shops nearby, and turn them into elements of their exhibitions.

11/ The future of museums is inside our own homes.

The picture, in fact, is very simple:

WE HAD:

- Epics

- Representation

- Monuments

- Histories

- Nations

- Groups and teams

- Large and expensive

WE NEED

- Novels

- Expression

- Homes

- Stories

- Persons

- Individuals

- Small and cheap

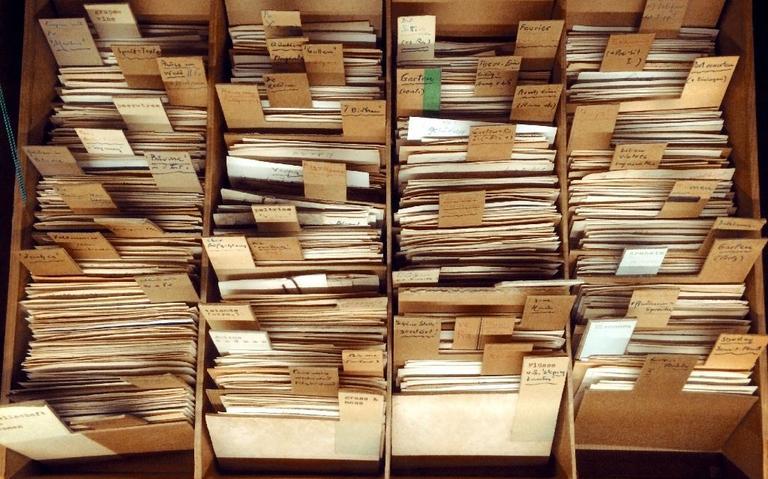

I love museums and I am not alone in finding that they make me happier with each passing day. I take museums very seriously, and that sometimes leads to angry, forceful thoughts. But I do not have it in me to speak about museums with anger. In my childhood there were very few museums in Istanbul. Most of these were historical monuments or, quite rare outside the Western world, they were places with an air of a government office about them. Later, the small museums in the backstreets of European cities led me to realize that museums – just like novels – can also speak for individuals. That is not to understate the importance of the Louvre, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Topkapi Palace, the British Museum, the Prado, the Vatican Museums – all veritable treasures of humankind. But I am against these precious monumental institutions being used as blueprints for future museums. Museums should explore and uncover the universe and humanity of the new and modern man emerging from increasingly wealthy non-Western nations. The aim of big, state-sponsored museums, on the other hand, is to represent the state. This is neither a good nor innocent objective.

I would like to outline my thoughts in order:

1/ Large national museums such as the Louvre and the Hermitage took shape and turned into essential tourist destinations alongside the opening of royal and imperial palaces to the public. These institutions, now national symbols, present the story of the nation – history, in a word – as being far more important than the stories of individuals. This is unfortunate, because the stories of individuals are much better suited to displaying the depths of our humanity.

2/ We can see that the transitions from palaces to national museums and from epics to novels are parallel processes. Epics are like palaces and speak of the heroic exploits of the old kings who lived in them. National museums, then, should be like novels; but they are not.

3/ We don’t need more museums that try to construct the historical narratives of a society, community, team, nation, state, tribe, company, or species. We all know that the ordinary, everyday stories of individuals are richer, more humane, and much more joyful.

4/ Demonstrating the wealth of Chinese, Indian, Mexican, Iranian, or Turkish history and culture is not an issue – it must be done, of course, but it is not difficult to do. The real challenge is to use museums to tell, with the same brilliance, depth, and power, the stories of the individual human beings living in these countries.

5/ The measure of a museum’s success should not be its ability to represent a state, a nation or company, or a particular history. It should be its capacity to reveal the humanity of individuals.

6/ It is imperative that museums become smaller, more individualistic, and cheaper. This is the only way that they will ever tell stories on a human scale. Big museums with their wide doors call upon us to forget our humanity and embrace the state and its human masses. This is why millions outside the Western world are afraid of going to museums.

7/ The aim of present and future museums must not be to represent the state, but to re-create the world of single human beings – the same human beings who have labored under ruthless oppression for hundreds of years.

8/ The resources that are channeled into monumental, symbolic museums should be diverted into smaller museums that tell the stories of individuals. These resources should also be used to encourage and support people in turning their own small homes and stories into “exhibition” spaces.

9/ If objects are not uprooted from their environs and their streets, but are situated with care and ingenuity in their natural homes, they will already portray their own stories.

10/ Monumental buildings that dominate neighborhoods and entire cities do not bring out our humanity; on the contrary, they quash it. Instead, we need modest museums that honor the neighborhoods and streets and the homes and shops nearby, and turn them into elements of their exhibitions.

11/ The future of museums is inside our own homes.

The picture, in fact, is very simple:

WE HAD:

- Epics

- Representation

- Monuments

- Histories

- Nations

- Groups and teams

- Large and expensive

WE NEED

- Novels

- Expression

- Homes

- Stories

- Persons

- Individuals

- Small and cheap